Something remarkable is happening. While we must be physically isolated, separated from the world and those we love, people are finding creative ways to reach out and foster community. From sewing masks for strangers to singing with your neighbors to organizing virtual family meals, acts of generosity and grace are breaking through what can feel like an insurmountable darkness. Author Rebecca Solnit spent time studying the aftermath of tragedies like September 11th and Hurricane Katrina for her book, "A Paradise Built in Hell." She found that people often responded to these monumental moments of collective trauma with solidarity, courage, and a drive to make change for the better.

Note: This is a rough transcript — please forgive any typos.

REBECCA SOLNIT: There are people organizing in most communities across the country and doing other forms of it in other countries to figure out how do we take care of each other in the context of not being able to physically be with each other in ordinary ways. And it's just extraordinary seeing both the intensity of this desire to help people you may never meet and the creativity and figuring out how to do it.

CHRIS HAYES: One of the things that's been strange about this moment we live in, there's a lot of things that are strange. There's a lot of graphs that look insane. And the reason there are a lot of graphs that look insane is because most of normal life, Wednesday looks like Tuesday and Thursday looks like Wednesday. But that's not in the case now for the last four or five weeks in American life. So, you can choose a graph. It's like air travel, or TSA throughput, or toilet paper purchases, or flour purchases for making bread. There's a million different graphs that just go along and then they shoot up and do something wild. And one of the graphs that does that is gun purchases.

So, you've seen, right when lockdown started, enormous, enormous spike in firearms purchases. And there were a bunch of new stories and photos of people lining up for those guns as we entered lockdown. And I think there's a sort of long, complicated reason why Americans would do that. But I think the animating idea behind it is a pretty familiar one, which is basically when you move towards emergency, catastrophe, or disaster, the civilizing influences of the social order fall away. And when the civilizing influences of the social order fall away, we are all thrown into a kind of Hobbesian maw, in which it is every man against every man. And you have to protect your property from marauders and looters. And when the resources get scarce, who knows who will be showing up to try to take what's yours. And so, you have to arm yourself.

And that's a really powerful idea that I think is often associated, particularly in, I think, filmic representations of chaos, of catastrophe, of disaster is the idea of the mob run amok, and the looting hordes, and order falling away, and violence spiking, and everyone's sort of out for themselves. But it's not clear that's a realistic portrayal of what happens in the midst of disaster, catastrophe, and crisis. In fact, there's a whole lot of evidence that the main reaction of human beings in those situations is kind of the opposite. It's not violent marauding. It's not taking up arms to hoard what's theirs, but it's solidarity. It's community, it's sharing, it's generosity, it's grace. And we've seen a bunch of examples of that, and we're going to talk about this in this hour in, in the midst of the COVID pandemic. But as I've been wrestling with all of this, I was thinking a lot about an author who I love and a book that I had read when it first came out years ago by Rebecca Solnit.

The book is called "A Paradise Built in Hell," and it was published after Katrina. And I remember reading it and it had a very profound effect on me because the thesis of the book is precisely this. It's a study of the aftermath of a variety of disasters, including the San Francisco earthquake, and Katrina, and 9/11 in New York. And what she argues in that book, what she shows really, is how often it's the case that people, the better angels of ourselves, are called forth in these moments. That there is a kind of, amidst the trauma, and tragedy, and danger, and awful grief and wounds of these moments, there is combined with that a kind of joy, or a kind of ecstasis, or a kind of courage, or a kind of community that's instantiated that's really beautiful and points towards how the world could be in good ways.

And so, I've been thinking about that book a lot. I reacquired it and have been rereading it. And the author of that book, Rebecca Solnit, is one of my favorite nonfiction writers in the English language. She's just a masterful prose stylist and thinker, and I thought I would really love to have a conversation with her about the themes in that book, which she's been kind of writing about a bit more amidst all this. So, without further ado, Rebecca Solnit.

CHRIS HAYES: It's great to have you. You know, that book made a really profound impact on me, and I thought maybe we can start out with you talking about how you found your way to the topic.

REBECCA SOLNIT: There was a series of things that happened. The major one is because the hundredth anniversary of the San Francisco earthquake and fire was coming up in 2006, around 2004, I got involved in a few projects to think about what had happened, started looking really closely at what happened, and then realized that the earthquake didn't do that much damage. Institutional authorities, treating the public as an enemy to be controlled, and making bad decisions was actually the most destructive force. And in the meantime, ordinary people were, as you note, remarkable, altruistic, creative, innovative, generous, putting the conditions of survival in a ruined city together.

And so, I had all that information in hand and had just written an essay about disaster for Harpers that actually went to press the day that Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. And so, I had the equipment to know that what the mainstream media was doing, which is to claim that there was mass panic, and looting, and savagery, and barbarism, and Hobbesian Social Darwinism, was almost certainly untrue. And that not only was it untrue, but it was terribly destructive. And it started to seem to me really important that people know what happened in disasters, not only in the aftermath of Katrina and its misrepresentation, but because with climate change, we're entering an era of intensified disaster in both frequency and impact. And so, I wrote A Paradise Built in Hell, and brought it out 11 years ago, and it's having an interesting life this month.

CHRIS HAYES: I remember that Harper's essay, actually, when it was published. Talk a little bit about what you discovered on both sides of the ledger in the San Francisco earthquake, since that's a fascinating disaster but, also, I think remote to most people. We don't think about it that much. And the idea of both sort of what people did and the ways in which the authorities were just responsible for a lot of the destruction and ruin that did happen.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. San Francisco had a major earthquake on the San Andreas Fault on the early hours of April 18th nobody was building earthquake-proof buildings. There was a fair amount of buildings that were damaged in ways, in various ways. Some people died, fire started. But the U.S. military, headed by General Funston, who had been a war criminal in the war in the Philippines, immediately assumed ordinary people would behave badly. And a lot of authorities assume what happens in disaster is that things are out of control. They see the fact that they are no longer in control as terribly dangerous because they assume the only thing that keeps ordinary people behaving well is the power of institutional authority with its threat of violence. So, the mayor issued a shoot to kill order for potential looting, which is the disaster moment for petty theft.

The army marched in. They may have shot as many as 500 people, sometimes mistaking rescuers and people trying to put out fires for people who needed to be suppressed, sometimes with guns, sometimes fatally. And they burned down a lot of the city because the fire chief had been killed in a building that collapsed and they had nobody giving them good advice about how to set firebreaks to limit the fire. So, it's often thought that the earthquake did this to the city, but a huge amount of what happened to the city was the failure of institutional authority to understand both human nature and some practical things, like how to fight fires. And in the media-

CHRIS HAYES: The fire.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah, go ahead.

CHRIS HAYES: Just to pause right there because the firebreak part of it is crazy, which is that after the earthquake, enormous fire breaks out, engulfing much of the city. The idea is the firebreaks are like when they dig a trench in a forest fire, right? You want to create a break where there's no fuel. And so, they're actually detonating buildings to try to rob the fire of fuel. But then, they're detonating buildings that have ... They're doing it all wrong, essentially. They're detonating buildings with chemicals, and they're actually acting perversely as accelerants.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. And they're just not smart enough to understand that black powder is not dynamite. So, they're setting things on fire. And also, they were trying to force people to evacuate their own neighborhoods. So, instead of allowing people to do what was really effective firefighting, which was wet gunny sacks and rocket brigades, putting out fires by hand, they were often driving people away from their own homes and neighborhoods. I believe some of the people they shot were because they were trying to defend their neighborhood. And so, they were actually doing the right thing, and the authorities were doing the wrong thing.

And we see, up into the present, that the authorities are often the problem, often accelerants and amplifiers of disaster in moments like this, not always. And I'm here in Governor Newsom's state, and we think he's doing a pretty good job. But I'm also here in Donald Trump's country. So, on the other hand. And people often think of my book as being entirely about these really socially positive things, but it's about the successes of civil society, with notable exceptions, including the racists in Hurricane Katrina, but also about the many kinds of failure of institutional authority and elites in moments like this.

CHRIS HAYES: One of the things that happens right is that the society of 1906 San Francisco is a very stratified society in many ways. There's racial stratifications, class stratifications, immigrant and native born, Chinese, Chinese-American and non-Chinese, which is a huge sort of divide in the city, as well. And yet, there's ways in which the disaster can exacerbate those inequalities, something we're seeing right now with COVID, but also transcend them. It's the latter story that I found really fascinating about ways in which civil society, in the midst of disaster, has a way of reaching across those divides. Tell me about that part of it.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. In the 1906 earthquake, people began to build community kitchens out of doors. Fires were banned. Fires were banned indoors because the risk of fire was so high and people didn't just build their own kitchens. They built them for each other and the butcher, the baker and the butcher, the baker and the milkman, these enterprises began distributing food for free to these community kitchens on corners. San Franciscans had a great sort of a spree decor in that moment, began labeling these kitchens with witty and funny signs and feeding each other, building temporary shelters, and things like that. There were moments when institutional authorities were good, as well, and helped provide shelter, temporary, and short-term intense long-term with what are called earthquake houses, which you can still find in some neighborhoods. But really ordinary people rose to the occasion, took care of each other, and in these moments, and we saw it in Katrina as we did in '06, commerce ceases to exist. Banks are closed. Storekeepers have either shut their stores or begin to give things away.

One of the horrible stories of 1906 was a storekeeper who'd opened his store for people to haul stuff away before it burned down, because the fire was approaching and some of the armed authorities deciding that these must be looters and shooting people, shooting somebody who was taking something the storekeeper had invited him to take. This is something you often see in disaster. I think we're seeing now with the obsession with reopening society so that profit can happen is people who are more passionately concerned with property than human life, more passionately concerned with finance and profit and in the present kind of Wall Street in the stock market than they are with survival. We saw that in 1906, and we're seeing other versions of that now.

CHRIS HAYES: There are these interruptions that you track throughout the book, and the one you just mentioned, commerce, that essentially markets as such essentially stop functioning in these environments, in Katrina after the hurricane. What you're left with is barter, mutual aid, human generosity, these other motivating factors to acquire or to distribute the needs that people need.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. That often gets called looting. In Hurricane Katrina, because it was a two-thirds black city, and most of the people were unable to evacuate because they didn't have the means, were black. That became an obsession of the authorities and the mainstream media. The word, looting, which we don't use for petty theft, and shoplifting, and whatever in ordinary times isn't even accurate in any way. Mostly what people are doing in disasters is provisioning themselves and others when there is no alternative. There are no ATM machines. There are no banks. There may be no storekeepers. There's no electricity. There's no way to buy the things you need, so people take them. They often take them in the most altruistic ways to help other people. People are looking for diapers, and formula, and clean water, and medical equipment, and things like that because they're trying to take care of each other. This is not people being selfish and opportunistic. It's being the opposite.

REBECCA SOLNIT: One of the most heartbreaking things, and you can probably still find the video on YouTube, is a major network personality inside the Kmart, not the Kmart, the Walmart in new Orleans, where a lot of stuff was being taken, including by the police in one of the country's most corrupt police forces at the time. But a small black boy has taken a pink t-shirt and this undoubtedly wealthy hosts sneers at him, "I don't think that's your color." I just watched that and I'm like, "Do you understand that this kid's mom could've swamped through raw sewage, or his aunt could have swamped through benzene and toxic chemicals in this incredibly hot city with 80% underwater? This kid is probably a hero trying to find clean clothes for the woman in his little community, and you're making fun of him on the national news."

That's the kind of humiliation and insult that comes out of that, but also people were being shot as looters, including by the police as though protecting property relations was the really important thing to do in this moment. Property is not what matters. Human life is what matters. I actually got to know a man named Denelle Harrington, who had been shot in the back point-blank for being black in a white neighborhood, which was part of the evacuation route on the Westbank of New Orleans, and almost bled to death before he was rescued by some good Samaritans who got him to the hospital where his jugular pierced by shotgun pellets was sewn up before he pled to death. All he was doing was trying to evacuate. He had stayed behind because he was helping his grandparents and other people in one of the housing projects. He could have evacuated. He was a hero, but a white supremacist saw him as inherently criminal and felt in the chaos, because not everybody behaves well in these moments, that he could get away with shooting him. He pretty much did.

CHRIS HAYES Was this in Gretna?

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. Oh, actually, I think Algiers Point. The investigative journalist, A.C. Thompson looked into the case, figured out who very likely was the assailant, and somehow there was never a trial. He also found Denelle, and got in touch with him. I spent some time with him, became a friend of his to some extent, and then lost track of him, and have never been able to find out what happened to him, and if he's still with us. He was such a good person, and it was so excruciating to hear his story, and to see how unreported this was. We're getting the small black boy with a pink t-shirt on national news, and nobody was asking why did this guy get shot point-blank with a shotgun for walking down the street, until A.C. came along years later.

CHRIS HAYES: This suspension of normalcy, one of the kind of themes and thesis of the book is that the suspension of normalcy poses a threat to the existing social order, the suspension of commerce, of property rights particularly. But even more broadly, I have thought about moments where I've been in disasters or in places where normalcy has been suspended the most. To me the most kind of banal version of this and also the most kind of least freighted with danger and grief is a snow day. A snow day is a great example because a snow day is generally not dangerous. It just means that no one can do the normal stuff. When you're a kid, and even I think when you're an adult, there's like an elation from that. It's like obligations have been removed from your shoulders.

CHRIS HAYES: I think one of the things you write about in the book is that even amidst horrifying anguish, that there is some part of that spirit, that obligations put on you by society, put on you by the social order have been removed, and there's some sense in which that provides people some kind of different experience that has a kind of ecstasis to it amidst all of the horror.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. I put it slightly differently just to say that everyday life is a kind of disaster of alienation and meaninglessness for so many people, and actual disasters, this sudden transformation and upending of everyday relations and systems, often liberates people from that. They suddenly have everything in common with the neighbors who are experiencing the same things. It's not true in this crisis, because we all are supposed to remain separate, but often they're able to come together physically and socially to improvise new systems of survival. There's a kind of immediacy. You're no longer worrying about whether your mother loved you when you were a kid or whether your pension funds are doing well. You're in the here and now. Often that sense of mortality makes people feel more vividly alive. There's a real sorting out of what really matters and what's trivial, and the kind of entertainment, culture, pop culture, gossipy stuff that a lot of us get caught up in, doesn't matter anymore. Your grandma, on the other hand, might matter a lot. People lead these really elemental lives.

What was so exciting for me about this research wasn't that people behaved well, but that they found in these moments often a real profound joy and sense of meaning and purpose that they felt was missing from their everyday lives. One of the instigation for it, I was in Halifax, Nova Scotia, after a hurricane there. The guy who told me about it, his face just lit up, the way everybody came out, everybody connected, everybody looked after each other was something he found so fulfilling and so meaningful. That I think most people do and that most of us miss. It's a desire we don't talk about much in a culture where we're taught we need lots of nice material things. We might need family love and romantic love and erotic love, but we don't really need public love, community love. But I think we need that greater membership and sense of belonging and purpose, and people often do find it in disaster.

I'm beginning to get the inklings people are finding it here, too, as I look around at all the extraordinary organizing going on. I don't think there's the same kind of joy, because people don't get to come together physically. It's so much more difficult. An earthquake or a hurricane seems so straightforward. It happens and then it's over. Physical things have broken. Some people have been injured or killed, but you kind of understand what's happened. A virus you can't see that might be in you or the lady across the street, you don't know, and this pandemic that doesn't really have any clear endpoint. It's a really different thing to deal with, but I am seeing extraordinary mutual aid and altruism in the organizing.

CHRIS HAYES: That, that you just talked about, those distinctions, and one thing before we sort of get to COVID I want to talk about that reoccurs in the book, and I've experienced myself, is public space and the refashioning of it. That in the wake of disaster, there's no cars, and streets are for pedestrians, and people can't be inside because structures are rickety, and there's sort of impromptu outdoor community gatherings. I definitely felt that way when I've covered aftermath of like a hurricane in Florida, that the- covered aftermath, of a hurricane in Florida that when the parking passes and you know that you're safe, that the landscape is just altered. It's not a normal landscape. People walk, you can walk in the streets, you can sit outside with people. There's this assembling. There's trees down in half the streets anyway, so there's no normal car traffic. And that was true, I think, in New York after 9/11 as well. It's certainly true in New York in the blackout that happened in 2003 when I was in the city. That was part of what made it special. But key to that was this congregation of bodies. People, you could get together in public spaces in a way that you couldn't normally.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. And there is a way people come together and live in public in a different way, that you and your neighbors, in an earthquake or hurricane may have all come out of your buildings, you're doing these things together, trying to dig other people out of the wreckage, or build a soup kitchen, or supply the elderly, or orchestrate an evacuation and you see these wonderful self organize efforts, whether it's the flotilla of boats on the morning of 9/11 that: ferry boats, tug boats, police boats, fireboats, et cetera, that just thought, "We need to get people out of lower Manhattan." And one of the not well known stories of 9/11 is that half a million people were evacuated by boat with nobody organizing. Because actually not only are people not chaotic, they're orderly in a self organized, horizontal way in these extraordinary ways.

And that's very equivalent to the Cajun Navy, as it was dubbed, a few years later in which hundreds of people with boats often having to sneak around the authorities that had turned New Orleans into a prison city. People couldn't leave or enter freely, snuck with their boats even as they're told these were terrible, dangerous, criminal people, to get grandmas off roofs and families off freeway overpasses and bring people out of the stranding into places where there were better resources and they could be helped. And so you see this kind of convergence often. And people are able to connect physically, which we're not now. And I have, as a San Franciscan, deeply ambiguous feelings about Silicon Valley and what the internet has wrought. But I have to say our capacity to connect online in so many different ways has felt like a real blessing in this moment, whether it's families having their Passover Seders by Zoom, or are continuing to teach classes, news people like you continuing to do what you do from home. All the ways we're able to be in touch while preserving physical separateness have been really helpful.

But I think there's that experience of ourselves as members of a public or a community that has a physical dimension in other disasters. It doesn't quite happen the same way in this one, although maybe it does. When all the Italians are singing on their balconies together, when somebody's reciting poetry on their balcony to all of their balcony dwellers in Tehran, when everyone's clapping or shouting for the medical workers, when police are teaching Zumba to people on their balconies in Bogota, that there are these polite ways people are experiencing the collectiveness of this disaster still, even in physical ways, I think, sometimes by orchestrating these things where they all do the same thing at the same time. And it's been really wonderful seeing people find really creative ways to continue being connected and to reach out in ways that they weren't connected before, whether it's helping an elderly neighbor with her groceries or some of the other things we're seeing.

CHRIS HAYES: It's interesting, the things you just mentioned, which I find so inspiring and I can't get enough of the people singing in Italy, and the Zumba classes, and the cheering for health workers and frontline workers. The other thing is about that as you sort of just listed it off, is that what makes this moment so strange is that the whole world is in the same boat basically. Usually these things are very localized. A hurricane hits a specific part of the country or a earthquake hits a very specific part of the country, a terrorist attack at a very specific part of the country.

CHRIS HAYES: Part of what makes this such a strange, remarkable moment is that the virus is making its way essentially across the entire world. And something about half the world's population right now is in some form of lockdown or shelter in place. And it's very rare, extremely rare that the same thing is happening in Rio de Janeiro, and Detroit, and in Tehran, all at the same time. And in Tuscany, which is everyone figuring out how to stay inside their houses and not go crazy. And there's something, I found something very moving about that, very deeply reconnecting to our basic shared humanity about that aspect of it.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. I think the 1918 pandemic that was also global, the influenza pandemic's the closest thing to it. And then World War II, and it's often said that this is the worst international disaster since the second World War, which wasn't truly global, and large swaths of the world were left out of it, Central America and in North America we didn't have, the war was not on our soil. Although we were interning Japanese Americans and doing other things, and building warships and things in my part of it.

But it is global and it's such also an interesting disaster. I just did a piece for The Guardian about all the ways that we're not quite in this together. If you're homeless or live in a dangerous home, or if you're a family of eight in a two room dirt-floored home in a third world country, that's really different than the kind of sheltering in place you and I are doing. You know that having kids and a full-time job is really different than if your kids you're supposed to school. There's so many different ways people are experiencing this, from those of us whose work carries on at home to those who suddenly lost their jobs.

And I feel like I haven't heard enough about the sheer economic terror of everything being shut down, and your job's been terminated and the U.S. botching any kind of swift and effective relief to those tens of millions of people. And so it is all a complex one, the fact that that black people in the U.S. are disproportionally affected because of many reasons having essentially to do with racism, including racism and poverty, racism and different health conditions, and things like that. The fact that we have such different experiences of it for so many reasons, from domestic violence, to poverty, to race, to access to resources, to whether our local and state governments are making good decisions. It's one of the things that makes this really complex in a way that's different than other disasters.

CHRIS HAYES: How do you think about the role that grief and collective grieving particularly plays in the ways that people deal with these disasters?

REBECCA SOLNIT: One of the things that I think's most striking about many kinds of profound difficulty including heartbreak, an individual, severe, and life threatening illness, a major loss of somebody you love, and these collective disasters is, I think there's a kind of opening up that your life pauses and you look around. What sustains me? Who can I lean on? What really matters in this moment? What really struck me about 9/11 is it felt like there was this great pause in which people really wanted to understand what happened and were ready to think in some very open-minded and fresh ways about what is our role in the Middle East? Why did terrorists want to do this? What have we been doing with the Taliban? How does our oil policy corrupt our foreign policy? And things like that.

And I felt like the frenzy of the Bush administration was not a reaction to foreign terrorism. It was a reaction to a insurgent imagination in the U.S. and they were working really hard to tell us to be afraid, to shut down that openness, to say that this was an act of war which we could respond to with war starting with Afghanistan. Which rather than that, this was a non-state actor. But we're told to be afraid of each other, to spy on our neighbors, to go shopping. There were those horrible America Open for Business, American flag shopping bags and posters everywhere.

And it really felt like that open-mindedness was the enemy and they did a very good job of shutting it down. So I think that there was grief, which was decent, and honorable, and unsurprising emotion. But I think that grief, often as there is with profound loss or profound danger, is also a kind of opening as people pause and look around to see what matters, what's substantial and worthwhile, and often come up with different answers. But the other thing about 9/11 and Katrina, which book end the Bush administration's success, and it feels like 9/11 gave them unlimited powers and Katrina took them away again. But in most major disasters, institutional authority has failed at the very least to prevent the disaster. And you don't expect them to prevent hurricanes and earthquakes. Those are natural phenomena. But when they haven't prepared well beforehand, and when they don't look after the public good in an honorable and egalitarian way afterwards, then they have failed. And these are very unstable moments when those who didn't benefit from the status quo are not necessarily eager to go back from it and profound change can and does happen. So there's also a conflict between often civil society and institutional authority and the leech who want everything to be like it was before it happened because that was working for them really well. And other people who are like, "No, actually that wasn't working for us and we don't want to go back to it." And so you do see some disasters like the Mexico City earthquake of 1986 unfold to some extent like revolutions, and I found war disaster revolution, economic collapse had a lot of overlap sometimes in how people responded.

CHRIS HAYES: It's interesting to, just to go back to that, what you were saying about 9/11 like my feeling about that emotional, the shared emotional experience was that the closest people to it, the feeling was profoundly grief and sadness as opposed to anger and revenge or let's go kick their ass. And there was some of that, quite a bit of that actually organically, I think. I don't think some people really felt that strongly as an initial reaction, people directly affected by it. But the cross state, I mean, I think, it was a little more organic. I agree with you about the openness. I think this sort of thirst for vengeance was a little more organic or there was some bottom up part to that as well as the message from top down.

REBECCA SOLNIT: There was, but I don't think it was a majority position. Some people definitely thought that way. Even a lot of people, and I read hundreds of accounts and oral histories talked to dozens of people who'd been in Manhattan during it and that was not a leading, it was definitely, it wasn't a leading sentiment. It was a loud sentiment.

CHRIS HAYES: I totally agree. Yeah, what I was going to say is like that one has always struck me about 9/11 is that, as a general rule, the further people were from it, the more they had this sort of anger, vengeance, and the closer people were to it, the more that it was grief and sadness, and over ... That was so much the overwhelming emotion of it, much more than we got to kick their ass. It was just the delocating nature of the shock and the trauma and the sadness and the grief and the sort of adrenaline and all those things. And very low down the list was that, that kind of gut anger that then got marshaled.

CHRIS HAYES: And I think that the idea about the return to normal and how loaded that is along various lines of societal division is so at the forefront right now because you have this near, this insane situation of a vocal group of people, largely wealthy people, and they're sort of propagandists, and Stooges wanting to march the country into untold death, destruction and misery because normalcy to them is so important.I mean that's really, and some people were saying it explicitly in ways that I actually find gobsmacking. It's very rare that you get people to come out and explicitly articulate their own ethical weight between the status quo, social order, and the lives of their probably human beings. People are just doing it all the time like constantly.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah. Yeah. And you know, and it's not really just returning to the status quo, it's returning to profitability, specifically to being back in business and propping up the markets. And I feel like, in a way, I never quite recognized before, these are people for whom dead things like money are alive and beloved in a tender hearted way, and living beings are dead to them in some way. I mean, who was it who said the other day that we should send America's kids back to school and that whatever it was like a 3% casualty was an acceptable rate and it's like, "Dude, you just said you're willing to let a few million children die."

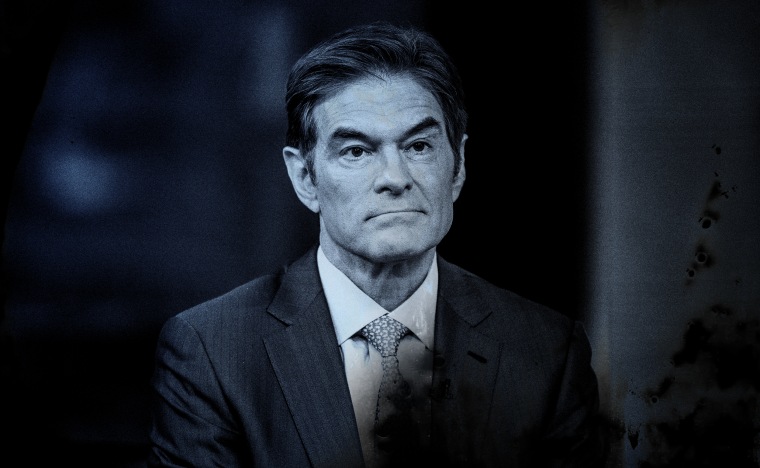

CHRIS HAYES: That was Dr. Oz, which, by the way, in the most charitable reading of that was that he was saying an elevated mortality rate that would be two or 3% larger than what it would be as opposed to an absolute two to three. This is me, I had this long discussion or editorial meeting and I was like, found myself weirdly defending Dr. Oz. But even the most defensible version of the position is still this very crass articulation of what one thinks of the value of your fellow humans. I mean, and that that value is everywhere in front of us. And I want to talk. I want to talk about that. I want to talk about what normal means and what disruption from normal means a little bit more after we take this quick break.

CHRIS HAYES: So, this idea of disaster is a break from normal and desire by the powers that be elites, institutional forces, governments, police forces to get back to normal is a real recurring theme in the book, and we're really seeing it right now.

REBECCA SOLNIT: I would say that police, firefighters, frontline workers probably don't believe that normal is going to happen anytime soon and don't have a lot to gain from it in this if normal means returning to the financial norms at the cost of a greatly enhanced pandemic. Mostly what I've seen is people who either have libertarian ideas of every man for himself or who think that the market is the most important thing in the country wanting to get back to normal, so to speak, as a way of getting the financial world back to normal without understanding that greatly escalated mass death and the probable failure of the medical system, et cetera, is probably not going to be really profitable among other things and really good for the stock market. So, it's like if they were even right, it would be less obscene and ridiculous, but they seem to not remember the reason we shut everything down is to limit the amount of death from this incredibly terrible virus.

CHRIS HAYES: Although there's a way in which there's an argument you make that is a kind of inversion of some of the things you talk about in the book in this way, right? So, one of the theses of the book is that people have this kind of collective solidarity with each other. They want to be together with each other and help each other in moments of disaster and the institutions and elite send the message to be fearful and that this is a dangerous time. And right now, there's something a little bit topsy-turvy about this, which is that the elite, the political leadership for the most part, not the president really, but governors and people like that are sending the message that it is dangerous and that you shouldn't get together with each other in large groups, and there's this rebel group that kind of wants to. It's slightly on its head in some ways.

REBECCA SOLNIT: And it's so interesting because you get the impression they don't want to come together because they all love each other and civil society and the collective good so deeply. They're very focused on it as an individual rights thing. And one of the things that was really fascinating in late February and early March was the way we all had to articulate to ourselves and each other that we are coming together by staying apart, that the gesture of solidarity is withdrawing from physical contact because we are with each other, we must be apart from each other. And I think most people get that, but most people is not everyone, and so the inversion yeah, that you have to remain physically distant to have social solidarity has been one of the peculiarities of this disaster that does have precedents and other pandemics, but certainly not in wars and earthquakes and the kind of disasters I talked about in this book minus a small section on smallpox.

CHRIS HAYES: But there is a way in which, the commonality that I keep thinking is just how a thing that keeps coming up in your book is just perspective, perspective, perspective, right? When everything is dangerous and blown away and the normal order has fallen, you get a certain perspective, like feeding myself and my family, clothing myself and my family, caring for the people in my community around me, making sure people are okay and healthy, and safe, and not like oh, I was feeling this career angst about whether next year I should do this or that. And I really didn't like the cushion that we got for that outdoor sofa. It's sort of been bugging me, should we get another one? All of that b------- that does take up mental real estate just is wiped away and I've definitely been experiencing that profoundly.

It really is a kind of just focus on what I have to do for my job, focus on what I have to do in the context of my family, stay connected to the people I love who are friends and I keep looking back on January and February where I had a lot of stress and anxiety about the future that was really tearing me up and giving me stomach aches and all that seems like such a waste now. Like what? Who cares, who cares? I was healthy and could go out to dinner. I went to Broadway shows where we all sat next to each other. What the hell was I worrying? What did I have to worry about then?

REBECCA SOLNIT: It's been really funny just thinking about how much physical contact we have with each other, whether it's the same subway straps, and doorknobs, and public restrooms, and churches, and just all the ways that we normally live in each other's germ space and having to withdraw from that. So, yeah, there is this return to what I think of as kind of elemental conditions. Like do I have food, water, clothing, shelter? But it is so different. There are people who stopped worrying about their couch cushions and other people who are probably terrified about how they're going to buy next week's groceries because we are not doing emergency aid very well in this country between slowing down the checks for Donald Trump's signature and how small the amount of aid is in many cases.

But what has been really striking also is the number of people thinking about the bigger picture about okay we need a universal basic income, we need universal healthcare, we need sick leave so people are not tempted to come to work sick because they're afraid of losing their job or their incomes. And we are seeing people thinking about big picture things like that that are progressive social goals antithetical to those get back to normal market goals. And you've seen workers do some really interesting organizing walking out on Amazon and a number of other big organizations and nurses in some medical spaces to demand safer, better working conditions and in some cases succeeding, and that's been really interesting organizing. And in some cases, it's about survival, but it is also looking to the big picture.

CHRIS HAYES: It's fascinating also calibration of labor value, which is that who's essential and who's not. There's a complete mismatch between what the market deems as the most highly paid labor and what is essential in a fundamental sense, so like farmworkers are essential because they pick the fruit and vegetables that ends up in the grocery store and the nation needs to be fed. And meat packers are essential, bus drivers are essential, janitors in hospitals are essential. None of those are remunerative in any way. None of them are rewarded with either status or money in our society, but in this moment, everything shuts down if they're not doing their job.

REBECCA SOLNIT: Yeah.

CHRIS HAYES: There's something really profound about that. That way in which conceiving of the value of a specific person's labor or specific job is completely recast in this moment.

REBECCA SOLNIT: One of the things that happened in 9/11 was that a lot of people, there was that whole right-wing rage at the federal government, Timothy McVeigh blowing up the Oklahoma federal building was not that far behind, was recognizing that the government also means people who died, people who are offering essential services, and of course, people started to really appreciate firefighters around the country. I have some in my family and thought I did already, but it was really moving seeing people recognize things, the heroism of these people, whether it's your house on fire or the World Trade Center on fire. I also have a lot of doctors and nurses and medical workers in my family and community and I would like seeing people recognizing the valor of what they do every day, going and dealing with pain, suffering, sickness, death, and sometimes putting themselves at risk.

The fact that almost no medical workers have just checked out, and here in San Francisco they asked for volunteers to go to New York City, 200 people from UCF volunteered, and they sent the first round of 20 people, so seeing that recalibration of what matters I think is really interesting and it does happen in different ways and people do want to also help in different ways. 9/11, and I live in a very liberal place, we were organizing antiwar movements while other people were chanting for war immediately afterwards, but all over the country people gave blood. For the sake of this book, I did the math. It was 125,000 gallons of blood that were donated immediately afterwards because people wanted to give and that they wanted to give literally from their hearts blood from their own body was about how intimate public life can be at times.

Now, I know I'm seeing women and I do believe men can so, but I'm only seeing women all over the country making masks from a few for the family to hundreds for strangers as another way that in a very personal way you can give. And that desire to give that's almost a need to give, which I saw in 9/11, I saw in Katrina, I'm seeing now is a really interesting part of human nature. And I think it's with us all the time, and usually, it's a lot of us make donations. Or volunteer at the soup kitchen. Or organize with our synagogue or our mosque or something to give, but there are these immediate direct urgent ways that people can give in moments like this and that it matters so urgently, and I'm starting to try and just take the measure of some of it and it's just kind of stunning.

Lexington, Kentucky has four different mutual aid groups and the Boston area there are half a dozen mutual aid groups using the term mutual aid. There are people organizing in most communities across the country and doing other forms of it in other countries to figure out how do we take care of each other in the context of not being able to physically be with each other in ordinary ways. And it's just extraordinary seeing both the intensity of this desire to help people you may never meet and the creativity and figuring out how to do it. And that is a really important part of who human beings are in times like this that I think is always dormant or latent within us.

It's as though it finds fertile soil to grow on in these moments and often is on barren soil around water neglected in other times because also people find this really rewarding that we are constantly told that what we want to do in life is take and of course the whole world of advertising and commerce is feeding our desire to take and to have, to eat this food, and buy this car, and own these flowers, or these shoes. But people really want to give and it's such an interesting thing that tells us something about who we are. We don't hear a lot about most of the time, but I think it's fascinating. I almost feel like it has to be suppressed to live in a capitalist market-driven, advertising-driven society, and it really emerges in times like this and shows us who else we are and what else life could be like. People want to give away things for free to strangers is a radical statement about human nature.

CHRIS HAYES: Rebecca Solnit is a writer and author. Incredible mind as you can hear. Author of "A Paradise Built in Hell," which came out years ago, and her latest, "Recollections of My Non-Existence." Rebecca, thank you so much.

REBECCA SOLNIT: A pleasure and an honor, Chris. Be well and thank you.

CHRIS HAYES: One again my great thanks to Rebecca Solnit, Author of “A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster” it came out in 2009. Her latest book is “Recollections of My Non-Existence.” We love to hear your feedback at #WITHpod, email us at withpod@gmail.com, tell us what you’re into, tell us what you want to hear, tell us what you’re into and how you’re keeping safe.

"Why Is This Happening" is presented by MSNBC and NBC News, produced by the "All In" team and features music by Eddie Cooper. You can see more of our work, including links to things we mentioned here by going to nbcnews.com/whyisthishappening.

RELATED LINKS

"'The impossible has already happened': What coronavirus can teach us about hope," by Rebecca Solnit