American football — a simple game in which a pig-skinned ball is thrown by muscle-bound men and one of the most popular and lucrative sporting activities in this country — is often marketed as a reflection of the brutal Roman gladiators, armed men who fought for the entertainment of crowds of people. The gladiators fought with spears and swords; American football players often use their heads (which house one of our most important organs) as their weapon in combat. Gladiators ultimately lost their lives in bloody combat; American football players often first lose their minds and then, ultimately, their lives.

My dad, Tommy Nobis, was one such fighter.

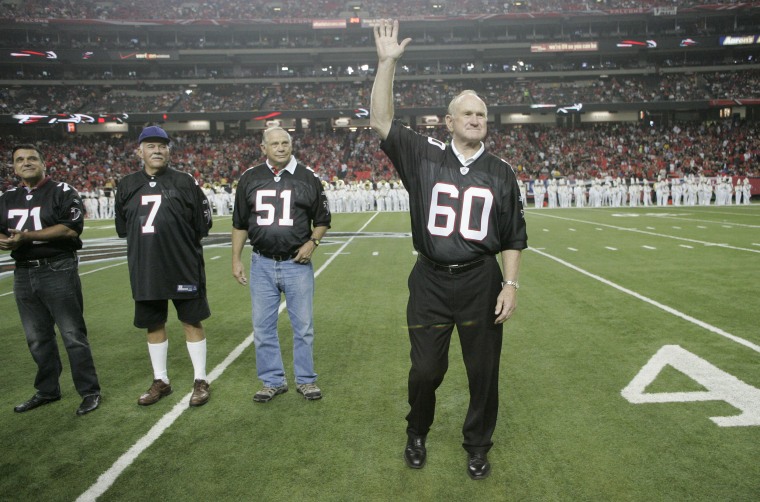

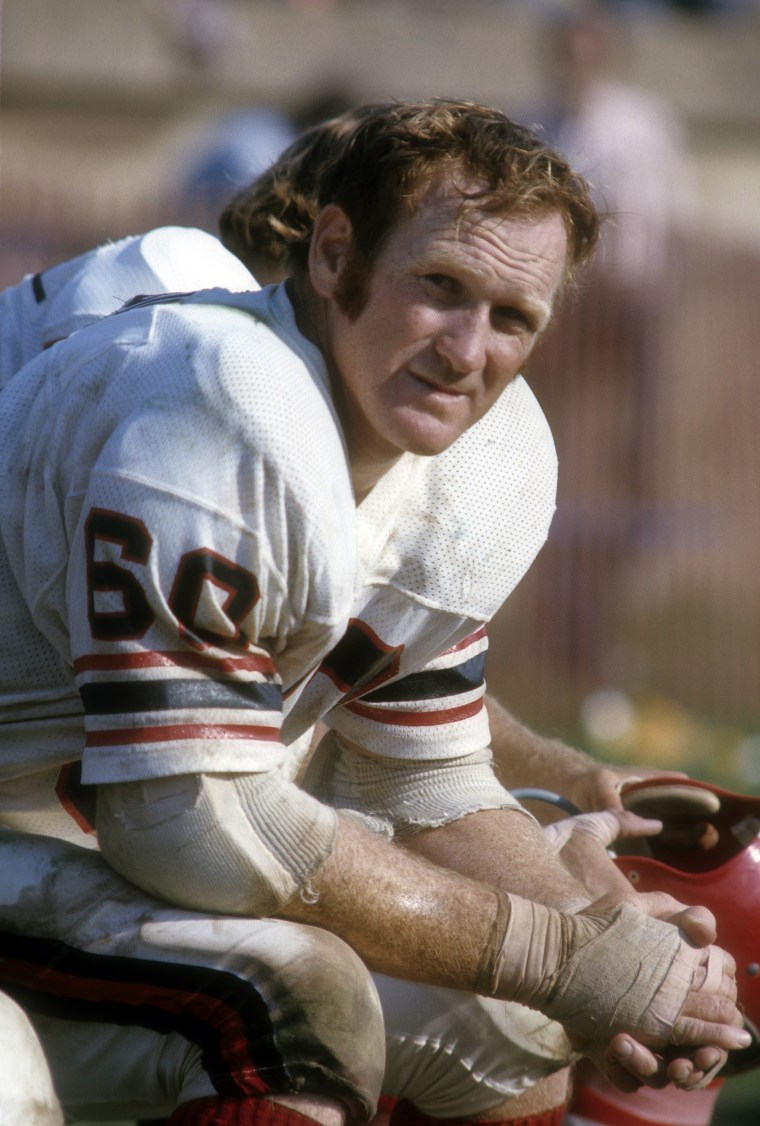

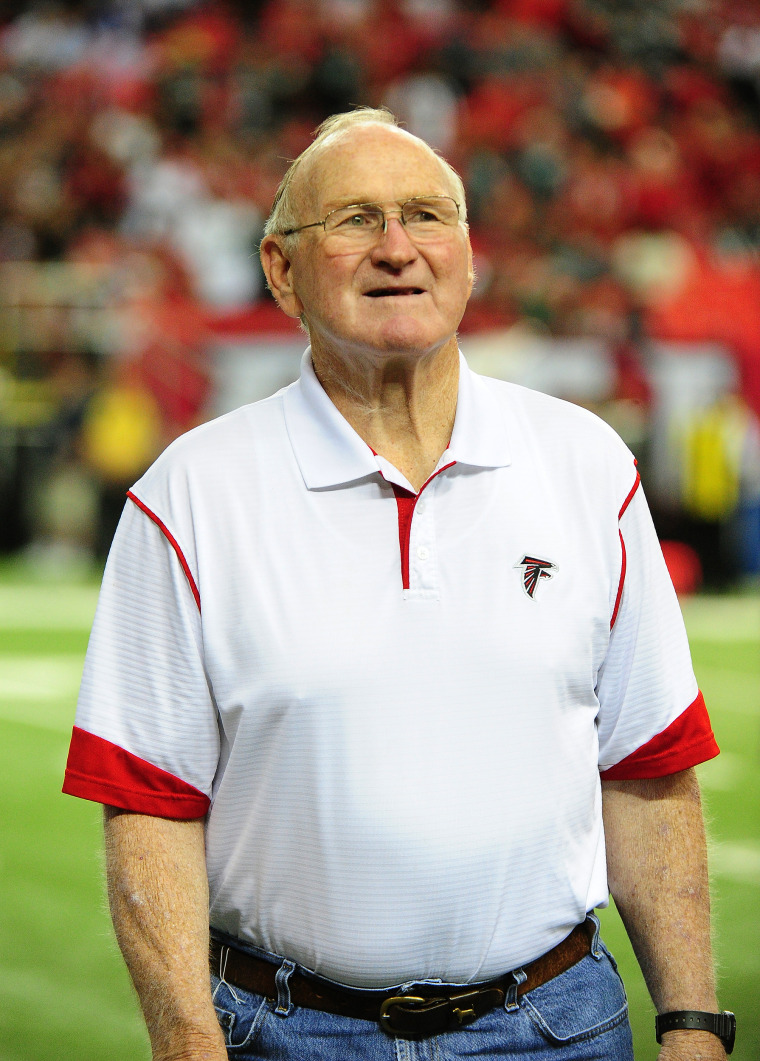

He had a lot of nicknames in his life: The Gentle Giant, Big Red, #60, Mr. Falcon, Huckleberry Finn with muscles, cowboy, Daddy, Good Samaritan. And there were so many other words to describe him: Prankster, dedicated, strong, humble, intense, unstable, full of rage, scared, paranoid, lost, sad, childlike and despondent.

But what we know now is that maybe none of us got to know the man he really was or could’ve been: A pathology report completed by Boston University’s CTE center after his death shows that he had stage four chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the most severe version of a condition caused by repeated blows to the head, and the worst the center had ever seen.

SIGN UP FOR THE THINK WEEKLY NEWSLETTER HERE

American football is an integral part of our society: It is our entertainment on a crisp fall Friday night, Saturday morning and Sunday afternoon; we use it to teach our children discipline, competition, and teamwork. It is the result of a strong brotherhood lured by the thrill of the battle; it is a diversion from the rest of our mundane lives.

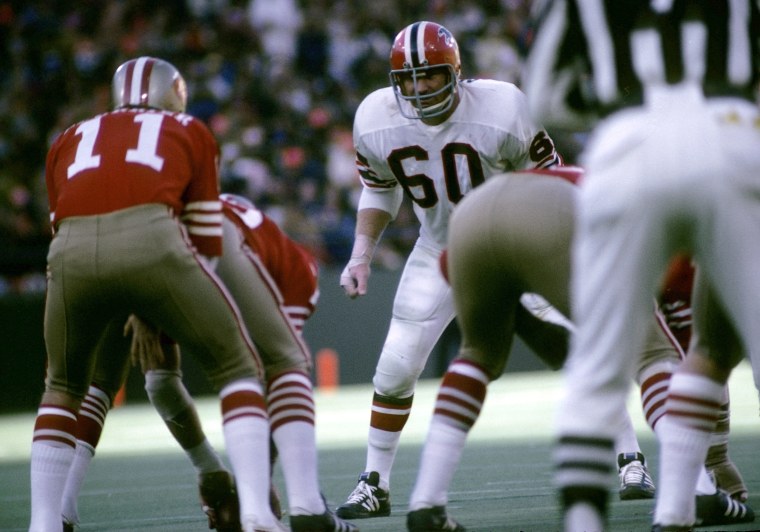

Football was the air my father breathed, and therefore the air we as his family breathed. It was my father’s identity, career, passion, and ultimately the cause of his death. He was trained to hit with his head, and he was good at it. From little league football to the National Football League, he played with reckless abandon. But every tackle was one more insult to his brain, which eventually became a muddled mess (not to mention his body).

Many memories of a childhood as my father’s daughter are as lost to me now as they were to my father before he passed; when you spend your early years on the defense, your only focus is to get through the experience, not delight in the moment. My father’s outbursts were not discussed but “brushed under the rug,” after which life went on without apologies.

Maybe he picked that up at work: A lineman who, at full speed, launches himself at his opponent knows that pain and injury might be a byproduct of the attack, but the harder the attack the better, and no apologies. But no one tells his family of the need for armor; we learned that the hard way

My father’s ability to remember anything faded slowly. As a motivational speaker, he was able to fool those who listened to him from the podium because he had a script, which was similar to his life. But, eventually, even having script began to fail him.

In his spare time, he helped found the Tommy Nobis Center — his second love — to help people with disabilities. But despite his love for the work, he had to scale back his participation in his last 10 years, and was unable to be involved at all for the last 5 years of his life.

Meanwhile, he became hostile and, many times violent. During his brief moments of clarity, he became more depressed about the reality of his loss of control. He became less “good” at things he used to be great at, like being a father or grandfather. In fact, for a period of 2 years, his children made the difficult decision to separate ourselves from my father’s volatile and aggressive behavior to protect our own kids.

By the end, my dad had lost the ability to remember where he lived, where he went to church, what meal he had eaten last. Before his death, he lived many days in a fog. Some days, we would find him in his favorite chair, either staring at the television or into space. Others, I’d wonder why my father had spent so many hours in the yard raking and sweeping; now I realize that it is a mindless activity. He was lost.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, caused by a career doing the thing he loved, robbed my father of his life long before he died. Although he finally lost his last battle at the age of 74, he fought like a gladiator with CTE for nearly half of those years. He was a true warrior who lived a life of humility, never crying out for the help we now know he deeply needed.

CTE has far reaching effects: Violence, crime, substance abuse, paranoia, depression and, ultimately, death. I find it increasingly difficult to believe that the game of football is worth it.

One day, maybe Americans become as wise as the Emperor Honorius, who closed the gladiator schools and ultimately prohibited gladiator contests. If we can’t end the game, then let’s at least stand firm to change this gladiator-like sport that calls our sons, brothers, husbands and fathers to sacrifice their lives for our passing entertainment. Our children would benefit; I know I would have.