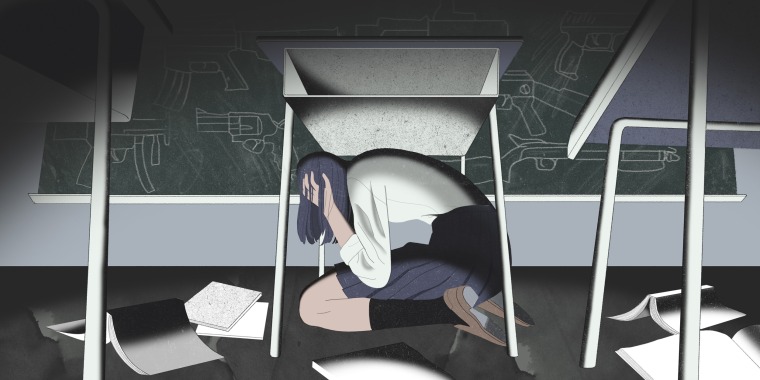

Last fall, during a particularly loud thunderstorm, one of our six-year-old sons ran under the coffee table and curled up in what looked like the yogic “child’s pose.” When asked what he was doing, he replied: “I’m doing turtle time, mom. At school, they tell me to do this and stay quiet if I hear scary noises.”

After the Parkland mass shooting, one of our 11-year-old nephews was having a conversation about what this latest tragedy meant to him. Very matter of factly, he said, “If somebody has a gun at school, everyone should run in different directions so that the fewest number of kids will die.”

A friend’s teenager told us that he “always looks for the closest exit” when he enters a crowded building. The child of a physician says that he regularly thinks about whether he would be brave enough to run at an assailant in order to save his friends. A teacher told us that she worries about which kids are too slow or too loud, and whether these traits — normal in young children — would get them all killed. Another child struggles with severe anxiety years after a mass shooting at her school.

The child of a physician says that he regularly thinks about whether he would be brave enough to run at an assailant in order to save his friends.

These worries should not be a normal part of childhood. In protest, students from around the country will be participating in this weekend's “March for Our Lives,” a large demonstration against gun violence. This generation of children has grown up with turtle-time, lockdown drills, ALICE maneuvers and the very real threat that a classmate will bring a gun to school.

Although, statistically, American youth are more likely to be exposed to gun homicide or suicide than to a mass shooting, no one knows whether or how the increasing frequency of mass shootings will affect our kids and our society. By day, we work as an emergency physician and violence prevention researcher and a clinical psychologist with a focus on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), respectively. But we are also parents. Our combined experience and expertise make us particularly concerned about these events’ psychological effects on American kids.

Research shows that exposure to terrorism leads to spikes in anxiety and post-traumatic stress among both children and parents. These spikes may last for months or years. Sixmonths after the Boston Marathon bombing, for instance, kids who had been at the marathon exhibited six times higher rates of PTSD than Boston youth who had not been physically present. Youth who watched more coverage of the Boston marathon bombing (and subsequent manhunt) were also more likely to have PTSD symptoms. Children who are exposed to war, even in a high-income country, have higher rates of substance abuse, post-traumatic stress symptoms and numbers of fights.

Research shows that exposure to terrorism leads to spikes in anxiety and post-traumatic stress among both children and parents. These spikes may last for months or years.

Mass shootings have many of the same characteristics as terrorism attacks. They are unpredictable. They are uncontrollable. And once they start, there is little that a kid (or a parent) can do to change the trajectory of violence. The survivors of such events are likely to see carnage first hand, and to know some of the victims who died. Indeed, one of the only studies looking at psychological health among youth after a mass shooting comes from Norway. In 2011, a single gunman attacked the youth and adults on a summer island camp. The youth who had been on the island during the shooting had six times the prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms, compared with other Norwegian youth who had not been on the island. Youth who had seen someone killed had even higher rates of symptoms.

But while there are similarities, there is also reason to suspect that mass shootings in the U.S. are different from other types of terrorism. The perpetrator is often a classmate or someone known to the youth, which is likely to disturb their sense of safety. The children exposed to mass shootings are often younger than those exposed to other forms of gun violence. The growing frequency of mass shootings, and their rapid dissemination and re-dissemination via the media, increases the “dose” of terror to which a youth is exposed. Thanks to Twitter, Snapchat and 24-hour news channels, it’s possible for youth and their parents who are far-removed from an incident to feel like they’re experiencing the trauma first-hand.

The more times someone is exposed to violence, the higher the likelihood of long-term behavioral health issues. The sheer frequency of exposures for our youth — in terms of frequency of attacks and ease of watching coverage of past attacks — is likely to have a negative effect with regard to amplifying traumatic stress responses and/or increasing “numbness” to these types of events. The effect of this “secondhand terrorism” on kids is, however, largely undocumented.

No one knows whether mass shootings lead to unique types of post-traumatic stress symptoms. Acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder can manifest in a myriad of ways, ranging from bedwetting to numbing to flashbacks to aggressiveness.

The effect of mass shootings on parents is also unknown. As specialists in this area, we suspect that the anxiety and worry we feel when we send our kids back school the day after a shooting is likely to trickle down to our kids. Parental anxiety is a strong predictor of mental health disorders after exposure to other forms of trauma; we expect the same is true for mass shootings.

More research is needed — and it is needed now.

Thanks to work with victims of community violence and other kinds of trauma, we can use our expertise to make best guesses for what we should do to help our kids and our communities to be resilient after a mass shooting. (Due to a continuing lack of Congressional appropriations for gun research, however, expert opinions are the best evidence that we have in this area.)

First and most importantly, parents need to take care of themselves. It’s like the old saying: put your own oxygen mask on first. It’s normal to feel anxious after an event like Parkland, but kids need adults to show them the way. If you’re feeling stressed, talk to someone; if you find that you’re not sleeping, are drinking too much, or are getting depressed, it’s particularly important to reach out for professional help.

Second, it’s critical that parents set limits around watching TV and social media that shows the aftermath — or replays the scene — of the tragedy. This repeated exposure will increase children’s (and our own) risk of post-traumatic stress.

Third, research shows that social support is one of the biggest factors in being resilient. Withdrawal is the worst thing to do in the aftermath of trauma. If you or your kid is feeling upset, even though the inclination may be to withdraw, reach out to friends and family. If you go to church, spend more time with your religious community. If your child belongs to a sports team, or if your extended family lives nearby, try to set up fun and distracting events. Creating normalcy will help prevent downstream consequences.

Research shows that social support is one of the biggest factors in being resilient. Withdrawal is the worst thing to do in the aftermath of trauma.

Finally, work with your kid to create a sense of control, and a sense of hope. This is one place where social media may be a real force for good.

Many Gen X kids were entranced by the story of Samantha Smith, a 10-year-old girl who caught the attention of the leader of the Soviet Union with her plea for peace. Her mission to eradicate nuclear weapons was inspiring. In the aftermath of Parkland, youth like Emma Gonzales are leading a different kind of movement. This movement is critically important for American communities: It may lead to change. But it’s also important for this generation: It gives them hope.

Not every child is Emma Gonzales, but almost every child can nonetheless take some action to help feel in control and to help feel like they can make a difference. Some ideas include writing letters to students at the affected school; volunteering to help youth who’ve been injured or who are sick in other ways; or raising money to cover community service projects.

Yes, America’s kids deserve better than living under this constant threat of mass shootings. But in the meantime, adults can try and prevent long-term psychological consequences. Parents especially can help children to find resilience. And as a society, the first step towards a world without “turtle time” is to support the belief that change is possible.

Dr. Megan Ranney is an Associate Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Rhode Island Hospital/Alpert Medical School of Brown University. and the director and found of the Brown Emergency Digital Health Innovation program (www.brownedhi.org) and director of special projects in the Department of Emergency Medicine. She is on Twitter @meganranney.

Dr. Rinad Beidas is an Assistant Professor in Psychology the Perelman School of Medicine at Penn. Her research focuses on the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) for youth psychiatric disorders in community settings. She tweets at @Rsbeidas.