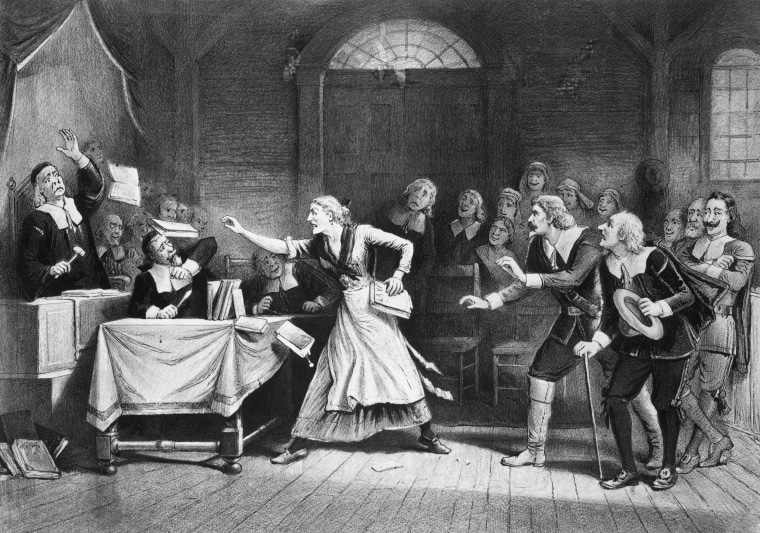

On a summer morning in 1692, Bridget Bishop, who was accused of being a witch, was hanged from an oak tree in Salem, Massachusetts, then dumped into a shallow grave. The thrice-married Bridget, 60, was decried for possessing dark powers by her stepchildren after her second husband’s death, in what may have been a bid to seize his property. She beat that earlier charge — but during the Salem witch panic, her luck ran out.

Out of the 16 falsely accused women of Salem and nearby villages who were either hanged or died in rat-infested dungeons awaiting execution, at least 13 were past their childbearing years, Jackie Rosenhek notes in “Mad with Menopause.”

In patriarchal societies — including our own — post-reproductive women have often been scapegoated as threats and burdens.

In patriarchal societies — including our own — post-reproductive women have often been scapegoated as threats and burdens. But many scholars now believe that these women’s presence is not only a defining characteristic of the human species, but the very thing that enabled us to flourish. (One theory is known as the “grandmother hypothesis.”)

Scientists know of only five species in which females outlive the reproductive stage. Humans are special in this regard, along with killer whales — where older females ensure the species’ survival by guiding their pods to food sources. Until the last few decades, many researchers assumed that in humans, this trait was a useless quirk or the “unintended” result of some other adaptation.

Turns out that the phenomenon is a happily adaptive feature, not a bug. In her deeply-researched new book, “The Slow Moon Climbs: The Science, History and Meaning of Menopause,” historian Susan Mattern presents strong evidence that menopause likely evolved in our Paleolithic past as part of a flexible reproductive strategy that bestowed our ancestors with crucial advantages. It helped them both thrive in good conditions, when older women were able to forage and help care for children, and make it through tough times, when resources were scarce and less reproduction was beneficial.

Unfortunately, in Puritan New England, Bishop’s age was likely a factor in her tragic fate. Historian Brian P. Levack reports that the majority of people accused during the witch-hunting spasms of early modern Europe (roughly the 15th century to the late 18th century) were women over 50. Those of middle age are thought to have been the most common victims.

Such women, historian Stephen Katz observes, especially those who never had children, were considered “the female group most difficult to assimilate” into the male-dominated social matrix. They may appear to exist outside the boundaries of society, using their knowledge and power to alter or escape the normal laws of the universe. They are unnatural.

Or are they? Mattern explains that from humanity’s earliest stages, women beyond childbearing years were not only energetic food-gatherers and essential caregivers, but also custodians of knowledge who passed along vital technological skills. We may have been formerly taught that the male Stone Age hunter was the hero of human success. But some researchers now speculate that it was actually the less-celebrated development of cooking that cast the die in our favor — a job typically performed by women, who may have been the first to domesticate plants.

From humanity’s earliest stages, women beyond childbearing years were not only energetic food-gatherers and essential caregivers, but custodians of knowledge.

In agricultural societies, middle-aged women became the bedrock of peasant economies — essential to food processing, textile production, health care, medicine and a wide range of farm work. They frequently ran farms when male relatives died, went to war or left as wage laborers — a pattern still true today.

But agrarian cultures also tend to intensify patriarchal patterns that subordinate women. In these societies, men typically control all or most property and then pass it on preferentially to boys – investing less in girls, who traditionally married and left the family. In most cases, women were unable to inherit land, and forced into dependence on male relatives.

Some destitute older women may have been targeted as witches because poverty made them economic burdens. Yet when they managed to secure independence, they were punished for that, too.

Consider Ann Nutter, a rich widow of 50 hanged as a witch during the famous Pendle witch trials of 17th-century England. Evidence shows she was possibly targeted for running afoul of the examining magistrate in a boundary dispute.

Other women challenged patriarchal structures because they were nonconformists or healers whose knowledge was held in suspicion during bad times, like the Little Ice Age (between 1300 and 1850 that coincided with the height of the witch-hunting fever.

Women, especially older ones, are still branded as witches today when communities are under threat or sense challenges to traditional power arrangements. In India, they are persecuted for witchcraft as an excuse to seize their lands and goods. Older women in Nigeria are also accused of dark magic and blamed for natural disasters and other calamities. Many are maimed and killed.

In the West, starting in the early 18th century as modern medicine began to develop, doctors (usually male) began to construe menopause as a medical condition characterized by hysteria, murderous derangement and nymphomania.

In the West, starting in the early 18th century as modern medicine began to develop, doctors (usually male) began to construe menopause as a medical condition characterized by hysteria, murderous derangement and nymphomania — dangerous symptoms to be treated with grotesque remedies such as toxic douches or the abstinence of sex and love. In the 1960s, physician Robert Wilson (backed by drug manufacturers, Mattern notes) wrote a bestseller called “Feminine Forever” describing menopause as a disease and a “living decay” that must be treated so that women could retain their youth and sex appeal.

Though Wilson has been discredited, the notion that women must undergo plastic surgery or expensive medical procedures to stay young keeps its hold on our psyches. Some experts are now calling for menopause to be “demedicalized” — viewed as a natural process in a healthy woman’s life in which only severe or debilitating symptoms should be treated, much the way we would now think of menarche.

In the United States, women no longer meet the fate of Bridget Bishop. But powerful older women who lead and speak out, like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, are still routinely taunted as witches. In Australia, Julia Gillard, the first female prime minister, was abused with the slogan, “ditch the witch,” while in Britain, one member of Parliament’s Christmas card depicted former Prime Minister Theresa May as the Wicked Witch of Westminster.

Right now, it looks like the most dynamic Democratic presidential candidate is a post-reproductive woman — an experienced teacher and a fighter for economic and social justice. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, powerful enough to push society’s transformation on several fronts, is the kind of woman that has always been necessary to help human beings move forward. President Donald Trump, meanwhile, has consistently used the term "witch hunt" to describe anything he doesn't like.

Empirical research shows that women are key to addressing major global problems such as poverty, religious fundamentalism, overpopulation and environmental challenges. Freed from the cycle of birth to nurture and guide, they are repositories of knowledge, relational skills and experience that could help us to avoid a catastrophic future of societal breakdown. Their vision illuminates society’s ills, like 1983 Nobel Prize winner in literature Toni Morrison, and their critical insights show us how to manage the Earth’s resources, like Elinor Ostrom, winner of the Nobel Prize in economics in 2009.

They are particularly needed in the public sphere long monopolized by men, where women’s ability to critique power is a crucial asset. Think of the three women celebrated in a 2010 Time magazine article as the “new sheriffs of Wall Street”: former Securities and Exchange Commission Chairwoman Mary Schapiro, former chairwoman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Sheila Bair and Warren, then head of the Troubled Asset Relief Program. All post-reproductive — but breathtakingly productive.

Perhaps the guidance of such wise women can help us to survive and thrive as it did for our ancestors.

Transitioning through menopause is neither a disease nor an anomaly — and certainly not a decline of vitality. Like menarche, it is part of the natural human life cycle and a stage to be celebrated as an important passage to greater wisdom, creativity and potential for leadership. Hardly nature’s mistake, it is nature’s gift.

Let’s hope the future brings the season of the witch.