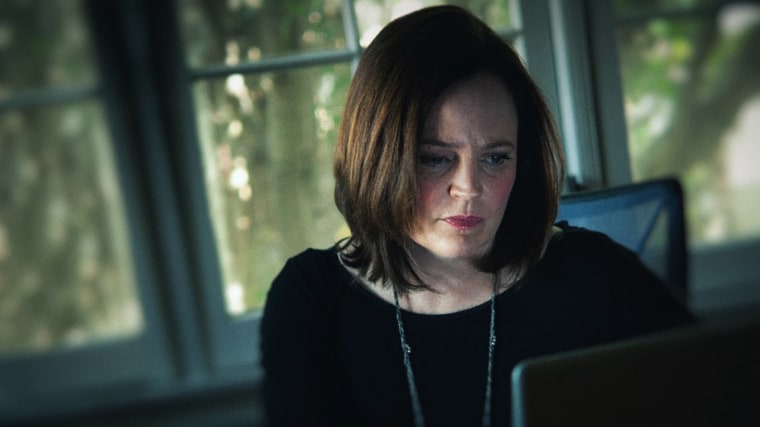

To true-crime aficionados, Michelle McNamara is a hero. HBO’s six-part docuseries “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,” named for McNamara's book, departs from the genre by charting not just the Golden State Killer's crimes, but also McNamara's evolution from true-crime blogger to published author whose book about the crimes became an instant classic.

McNamara spent years investigating an increasingly violent spate of burglaries, rapes and murders in Sacramento and its environs, as well as a series of similar crimes in Southern California that law enforcement had deemed unrelated. Police attributed the former to the East Area Rapist and the latter to the Original Night Stalker, but McNamara coined the moniker "Golden State Killer" for the criminal responsible for them all.

Although she didn’t live to see her book's publication — her research partner Paul Haynes and fellow reporter Billy Jensen finished it with help from her widower, Patton Oswalt, after her death in 2016 — some believe her work had at least something to do with resurrecting law enforcement’s interest in the cold cases. Eventually, authorities arrested retired police officer Joseph DeAngelo in 2018. (He is set to plead guilty as early as Monday in a deal to avoid the death penalty.)

McNamara is beloved for many reasons — her dogged determination and curiosity, her voice as a writer, her ability to win the trust of survivors and wary former detectives alike — but especially because she was one of us true-crime fanatics who spend sleepless nights skimming subreddits, even when it gives us nightmares or seeps into our daytime life.

Oswalt gave director Liz Garbus incredible access to McNamara’s files, both professional and deeply private. The final product shows her as a sister, friend, daughter, mother and wife — and as a flawed human who, like many of us, was drawn to true crime for reasons all her own.

It is, however, an odd time — when people around the world are demanding a sea change in policing — to look back at when true crime as a genre was in its ascendency. True crime, like police procedurals, has often reinforced myths about the justice and carceral systems. The genre has been, more broadly in the last four years, justly criticized for playing into the fears and interests of white women. There are, of course, far fewer Ted Bundys (or Joseph DeAngelos) lurking outside our suburban windows than there are murdered and missing Black, brown and Indigenous people, and there are far more Asha Degrees than JonBenét Ramseys.

True crime has often played on white people’s fears of being victimized, which has been used to justify increased policing and mass incarceration, when the simple truth is, and always has been, that the more marginalized you are, the more at risk you are for violent crime. This includes crimes committed by agents of the state, like Joseph DeAngelo. As a lover of the genre, it’s fair to question why we have focused so intently on criminal outliers when the immediacy and widespread nature of police brutality is, and has been, constantly in our faces.

That said, true crime can also push the conversation about justice and free survivors of domestic and sexual assault from shame, as “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark” helps show. The director, Garbus, used her work to offer survivors the chance to talk about their experiences both at the hands of the Golden State Killer and at the justice system and society at large in the 1970s and '80s. As the Los Angeles Times reported in its series about the rapes, “Man in the Window,” sexual assault was, at best, treated like any other kind of physical assault back then and, more often, treated like something of which the women themselves ought to feel ashamed.

While some of the victims seemed retraumatized by DeAngelo’s arrest — or were perhaps addressing their trauma for the very first time, given how little space they were allowed to deal with it then — it’s clear they found power in speaking out about their experiences and in the bonds they formed with each other.

The unspoken question here is whether or not anyone could have stopped the Golden State Killer at the time. Speculation then that the unknown suspect could be a member of the police or military — DeAngelo was briefly a member of law enforcement and is a Navy veteran — didn’t prompt any agency to scrutinize themselves that hard. Plus, what screenings for psychological issues there were, or are, in law enforcement regularly missed abusers.

And, of course, there is the ever-present question of what could happen if police made sexual assault a priority. But even now, RAINN reports that while about 3 out of 4 survivors do not report their sexual assaults to the police, the rate of arrest and conviction for the ones that are reported is dismal — and that’s not even getting into the enormous backlog of rape kits. For some survivors of sexual assault, going to the police can literally add insult to injury.

One argument for not defunding the police at the moment is what to do about men like DeAngelo, or rapists in general. But the truth is that it took people like McNamara — and the publicity she generated about the white victims in this case — to remind police that these cases were open. When it comes to survivors of sexual assault, the police have hardly acquitted themselves particularly well in the broadest of senses. These arguments against defunding play into the same fears as the true-crime genre itself: that we, as white people, are likely to be victimized, and need something to save us from that chaos.

But that’s not really how the police operate.

In a recent episode of the podcast “The Murder Squad,” hosts Billy Jensen (McNamara’s posthumous writing partner) and Paul Holes (a retired cold-case investigator who focused on the Golden State Killer and was an unofficial partner of McNamara’s) dedicated an entire episode to the idea of defunding the police and what that might look like for the future of crime. While the episode didn’t go far enough to explain how and why defunding the police might be necessary or how it would really work, it is pretty remarkable for a former detective to address the inherent problems in the system as it currently stands.

Maybe in the future, we can and will find a better way to get justice for all victims — not just the ones who look like me and McNamara — whatever that may look like.