This has been a summer of protest, with thousands upon thousands of people from all different backgrounds marching through the streets condemning racial injustice and the killings of men and women like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Astoundingly, during this powerful movement to fight the pervasive, structural and historical forms of racism in our country, just 18 days after George Floyd's death, another police officer shot and killed Rayshard Brooks, yet another Black citizen. If we do not want racist grown-ups in our political, education, health and criminal justice systems, we need to start changing these systems from the ground up. That starts with our children.

If we do not want racist grown-ups, we need to start changing these systems from the ground up. That starts with our children.

As social developmental psychologists, we recognize the challenges involved in forming egalitarian adults. Even infants see race, or at least skin color. Then, as early as preschool, children, especially from majority racial groups, show favoritism toward their own groups over others. Yet psychology also suggests strategies that can promote racial equality and positive interracial relationships starting from childhood. And these strategies begin with debunking the idea that children can (or should) be colorblind.

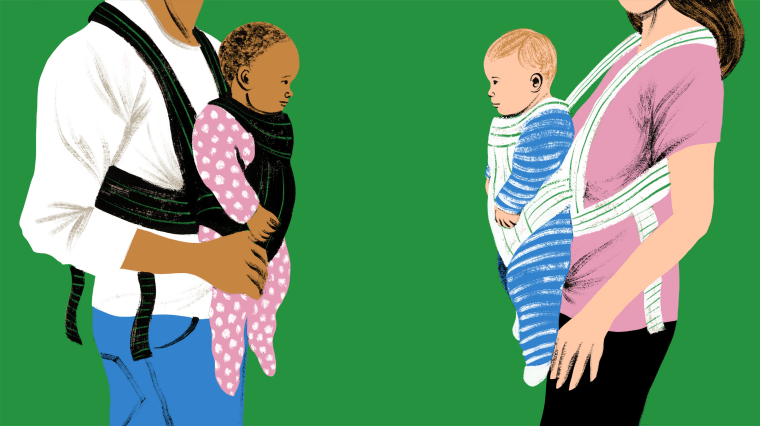

As early as 3 months old, infants begin to distinguish faces from their own racial group better than faces from other racial groups. This is even more true for infants with little exposure to people from different backgrounds. Thus, exposing our children to diverse children and adults has a direct link to how they will see race going forward.

Moreover, children in preschool and kindergarten already attribute positive traits to their own groups — their "ingroups" — over "outgroups," whether the group is based on race, gender or even random assignment (e.g., children given red versus blue T-shirts). In other words, children learn to think their own groups are nicer, smarter and friendlier than others.

Psychologists have posited several reasons for this tendency: It boosts our own self-esteem to think our group is better than others; we like what is familiar; as humans, we naturally categorize objects and people into groups; and in our evolutionary history, tracking which groups were friends or foes was integral to survival. And these tendencies might be particularly powerful when fear is involved.

Therefore, the above findings imply that colorblindness is impossible. Race must be acknowledged and discussed, since children clearly see race. Yet many parents, likely in an attempt to promote egalitarianism, take a colorblind approach about race with their children, meaning they simply never discuss it or ignore it entirely. That is a mistake.

In response to videos of Black Lives Matter protests, parents' first impulse may be to protect their children by not talking about race. However, silence interferes with the work of dismantling racism. In fact, in schools, silence on matters related to race has been linked to students' being less likely to call out explicit racial discrimination. Long-term silence will simply not protect the many children of color vulnerable to discrimination.

Your child sees race, which means you need to discuss it. The good news is that discussions about race can reduce both children's and parents' levels of bias. But here is where it gets more complicated. Although discussions generally about race are necessary and important, those discussions need to go beyond simply labeling or defining people by race.

Research suggests that racially labeling others ("Simone is Black") could be harmful because it might lead children to believe that all people with the same label share the same inherent qualities. And this fixed or essentialist thinking about race is associated with increased stereotyping of others. Therefore, although it might be necessary to racially label others to advance conversations about race, parents and educators should not dwell on these labels but, instead, delve deeper and expand conversations about the heritage of each group and the rich differences within them, too.

For example, teaching children to recognize and confront discrimination can change a school's climate, decrease stereotyping and increase desires for equity. For example, parents could explain to children that sometimes others do not treat Simone fairly because of the color of her skin. To promote racial empathy, parents could then ask children to think about how they would feel if that happened to them. Explicitly teaching elementary school-age children about racial discrimination experienced by historical figures is another effective approach. Or giving children practice verbatim phrases to use (e.g., "Give it a rest, no group is best!") can also lead to increased challenging of discrimination and less stereotyping.

Another action to take? Increase your child's diversity of activities by encouraging cross-race friendships, experiencing cultural events and visiting new places. Long-term, meaningful and positive contact or exposure to outgroup members is one of the best pathways to positively influence attitudes and behaviors. Finally, providing children with positive role models from other racial groups has also been shown to reduce prejudice.

Many of us want to live in an egalitarian society and want to make choices to make that a reality. But the change we need now cannot happen if the acknowledgment of race, racial differences and anti-Black prejudice, in particular, remains absent.

We may feel inept when trying to help our children talk about race, fearing we may say the wrong thing. We may want to shield our children from feelings of guilt or anger. But that discomfort can motivate children and adults to work toward equity. We need to find the courage to speak openly with our children about racial injustice. We need to acknowledge, understand and transform the racial bias that can lurk within us from childhood.