Her emphasis on the public provision of services for women and children infused the key international United Nations treaty on women's rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, which has been ratified by 187 countries (but not the United States).

After World War II, East European nations hoping to mobilize women into the labor force implemented updated versions of her early Soviet reforms liberalizing divorce, expanding parental leaves, building kindergartens and socializing domestic work, spreading what we now recognize as feminist ideas across the globe to countries like China, Cuba, Vietnam and Ethiopia before they were part of any U.S. presidential platform.

She also served as the Soviet ambassador to Sweden throughout World War II and was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize — in 1946 and 1947 — for brokering the Finnish-Soviet ceasefire.

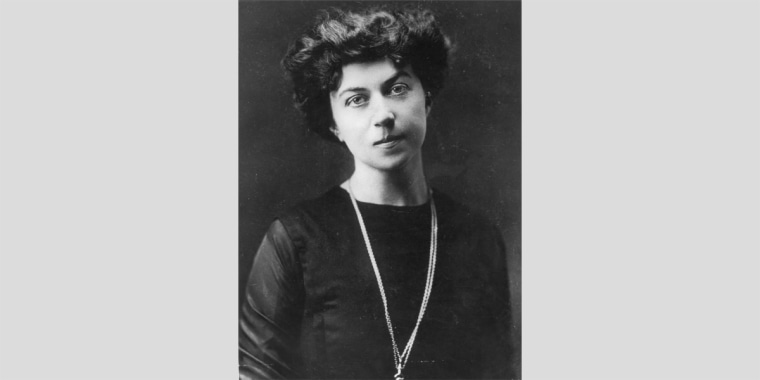

Despite all of that, even during Women’s History Month, you won’t read much about Alexandra Kollontai — a woman so dangerous that the United States government once deemed her a national security risk. Because she was a socialist and an early 20th century advocate of sexual freedom for women, Kollontai still gets written out of the “herstories” of global feminism.

Born in St. Petersburg in 1872, Alexandra Mikhailovna Domontovich hailed from the upper class and, as a child, watched an older sister marry a man 40 years her senior because he was wealthy, after which the budding feminist questioned the transactional nature of marriage. Later, over the fierce of objections of her mother, Alexandra, then 21, married a poor cousin named Kollontai and eventually had a son — but politics were her true passion.

Although there was already a women’s movement in Russia, Alexandra Kollontai questioned whether “bourgeois feminists” would ever really lift working-class women out of their misery. The women of the movement advocated primarily for suffrage, women's education and access to the professions — as well as married women's property rights — and often ignored the unique needs of their less fortunate sisters working in factories or on farms. Kollontai, though, understood that programs and policies to emancipate all women could only succeed in alliance with economically disadvantaged men and other groups marginalized within a capitalist economy. In the early 1900s, she worked among female textile workers in St. Petersburg, distributing literature and raising money to support women-led strikes.

Inspired by August Bebel's 1879 book, "Woman and Socialism," Kollontai also saw the institutions of marriage and the traditional family as contributing to women's oppression. Even if women worked outside of the home, they remained responsible for vast quantities of unpaid work in the domestic sphere, which they performed individually for their husbands and children. These household labors would continue to prevent women and girls from taking advantage of educational and professional opportunities even if they became available. Only collective childrearing and the socialization of cooking and cleaning would liberate women to pursue their own goals in the formal economy, which would provide them the economic independence to exercise full autonomy over their own lives.

In her 1909 pamphlet, “The Social Basis of the Woman Question,” Kollontai wrote: “In the family of today, the structure of which is confirmed by custom and law, woman is oppressed not only as a person but as a wife and mother, in most of the countries of the civilized world the civil code places women in a greater or lesser dependence on her husband and awards the husband not only the right to dispose of her property but also the right of moral and physical dominance over her."

Kollontai also promoted radical ideas about women's sexuality during an era characterized by Victorian prudishness. She argued that sex was a natural instinct, like hunger or thirst, and that women's natural sexuality suffered under an economic system where it became a commodity to be bought and sold on marriage markets. By granting women economic independence and liberalizing divorce, Kollontai believed state policies could usher in a new world where couples came together for reasons of love and mutual affection rather than crass monetary exchange.

Hounded by the czarist police, Kollontai spent years in exile, in and out of prison but returned to a Soviet Russia in 1917, where Lenin named her minister of social welfare in the first Soviet cabinet. Kollontai spearheaded drastic revisions in Russian family law and organized the socialization of women’s domestic work through a vast network of public children’s homes, laundries, cafeterias and mending cooperatives.

The new 1918 Family Code reversed centuries of ecclesiastical and patriarchal power over women’s lives, rendering women the juridical equals of men and reducing the previous obligations of marriage. Married working women retained complete control over their own wages. The new law also abolished the category of “illegitimate” child, making all children equally deserving of parental support and guaranteed state guardianship for orphans.

For the implementation of these policies, Kollontai became an international pariah to nervous male leaders in the West. In 1918, "Current Opinion" called her the “Heroine of the Bolsheviki upheaval in Petrograd” and announced to its incredulous readers that “she holds a cabinet portfolio, dresses like a Parisian and does not believe in marriage.”

In 1924, after she entered diplomatic service, The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that the “Communist Valkyrie is [a] match for any man in diplomacy.” A year later, The New York Times accused her of arranging fake marriages to promote “red propaganda” in Norway.

In 1927, The Washington Post revealed that the new Soviet diplomatic envoy to Mexico — “who has had six husbands” — had been refused a landing in the United States. Her worldwide reputation as “the Red Rose of the Revolution” or the “Jeanne d’Arc of the Proletariat” unsettled the Americans, who feared her mere presence might incite public disorder.

Stalin, meanwhile, paranoid about an imminent invasion of hostile Western powers, eventually reversed most of Kollontai’s work. The falling birth rate threatened his plans for rapid industrialization, as the Soviet Union required the bearing and caring of a new generation of workers and soldiers. The importance of alleviating women's domestic burdens faded into the background until the publication of Natalya Baranskaya's explosive 1969 novella, "Week Like Any Other," exposed the continued double burden Soviet women faced as they struggled to combine mandatory formal employment with domestic responsibilities.

Alexandra Kollontai, though, managed to survive the violent purges of the 1930s, and lived long enough to see her initial policies revived in the countries of Eastern Europe after World War II. Her early experiments in the USSR then infused progressive women’s organizations and movements around the globe. Even in the United States, many influential figures like Betty Friedan were leftists before they became feminists and African American women like Louise Thompson Patterson and Esther Cooper Jackson joined the Communist Party USA to advocate for gender equality.

From our vantage point in the 21st century, it's almost impossible to imagine how radical Kollontai's legislative reforms were in the late 1910s and ’20s. In terms of women’s rights, they were unprecedented not only in Russia, but in Europe and North America as well. Compared to women in the Soviet Union, women in the capitalist West would only achieve these rights piecemeal over the next six decades. In many ways, American women benefitted indirectly from Kollontai's long history of activism because Cold War superpower rivalries forced the U.S. government to pay attention to women's rights.

We live in a world that Alexandra Kollontai helped create over 100 years ago — but her accomplishments have been written out of our collective "herstory" both because of her allegiance to socialism and because of her radical ideas about liberating women's sexuality by building societies that guarantee everyone robust opportunities for economic independence.