I have a soft spot for people who have spent time scrounging around for a rogue shard of crack, found it, and stuck it in a pipe only to realize they were smoking a bit of Parmesan cheese.

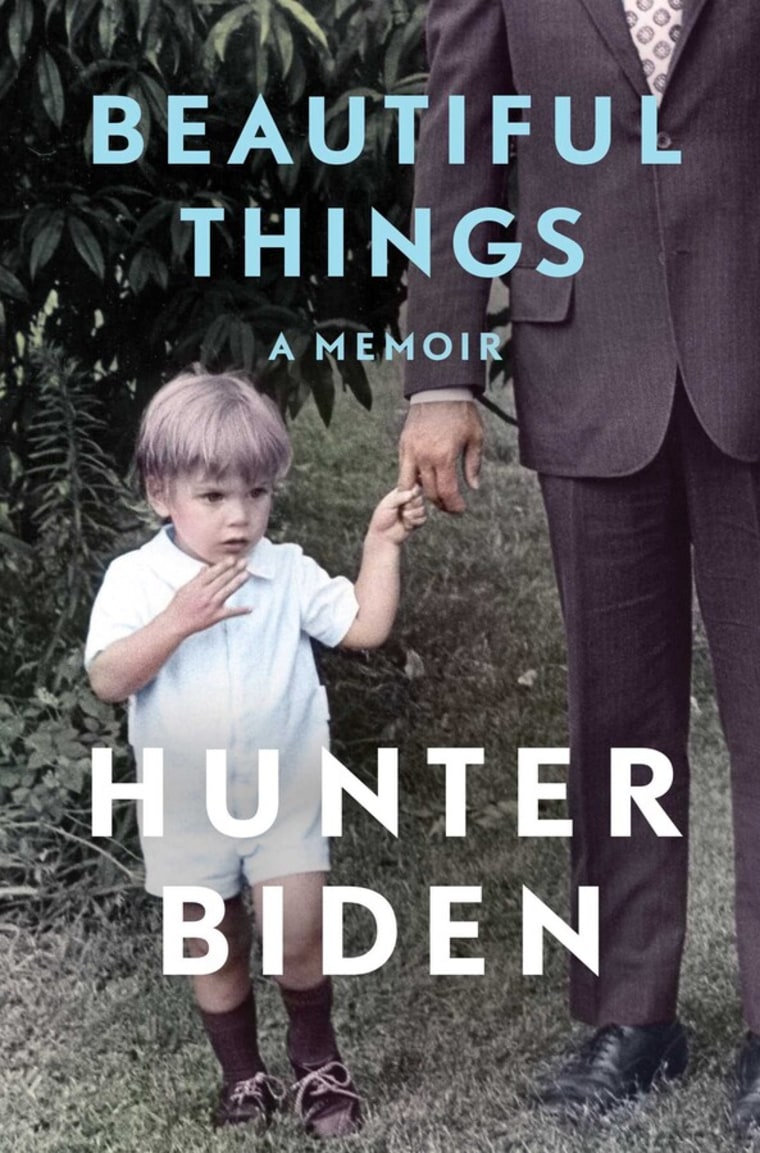

And so, after reading his memoir, “Beautiful Things,” I have a soft spot for Hunter Biden.

There are three things you should know about this crackocalyptic memoir: First, there are moments of great beauty and tenderness; second, that it is an interesting keyhole into the president’s family life; and third, you may not want to ask Hunter for advice on how to get sober.

“Beautiful Things” is an eye-popping “drunkalog,” AA-speak for the alcoholic’s origin story in which people tell, in a nutshell, what it was like, what happened and what it’s like now. The goal of these stories is to show newcomers that they, too, can get sober, and to talk a bit about specific solutions to the drinking problem.

The back cover of “Beautiful Things” features four blurbs, including contributions by Stephen King (recovered alcoholic), Anne Lamott (recovered alcoholic) and Bill Clegg (recovered alcoholic and addict), which gush about Hunter’s vivid accounts and his raw honesty. But conspicuously absent is that unmistakable sense of gratitude a person in recovery feels when confronted by a story that challenges and inspires them to not only hold on to the true north of their recovery, but also expands their sense of why sobriety matters.

While Hunter Biden very clearly states that AA wasn’t for him, it does work for many people.

In “Beautiful Things,” the jailhouse of addiction is always on the horizon. The happy, joyous and free part that sober alcoholics like to talk about — well, not so much.

Hunter’s story includes some familiar elements (a history of family members who “couldn’t handle their liquor”) and the usual cast of characters that inhabit a rich addict’s world — crooked drug dealers, soft-hearted bartenders, strippers, a couple Samoan gangsters — as well as his neat-freak crackhead roommate whom he calls Rhea. She weighs “85 pounds soaking wet,” and feels like a character from the cutting room floor of “The Wire.”

It also has Hunter in stints at fancy rehabs, on recovery trips spent on synthetic ayahuasca in Tijuana, Mexico, cooking crack at the trendy Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, and hiding out in mildewy motel rooms along the I-95 corridor. There are con jobs, unanswered calls from the future president, a smattering of interventions, supposedly curative Ketamine infusions and that recovery cure-all, yoga. The sheer volume of catastrophe and dysfunction is turned up to “movie deal” volume, which is where the rubber left the literary road for me.

While there’s no right way to get sober, “Beautiful Things” ends in what feels like a cliffhanger.

It’s too bad, because the first part of the book is so evocative I’d like to read it again. A vivid world is summoned in those pages — a narrative that weaves alcoholism and addiction into the heartbreaking experiences of loss and grief of both the Biden family and Joe's first wife's (Hunter's mother's) family. And that narrative did what it was designed to do — lead the reader to a trapdoor. That’s the one that opened under Hunter when his brother, Beau Biden, died.

The road accident that killed Hunter’s mother and sister is followed by a filigreed account of the days leading to Beau’s death. Beau emerges as a devoted sibling, shepherding Hunter to AA meetings and rehabs, always there, a forever best friend. As Hunter writes, “Beau left a hole that was hard to fill.”

But in the last few chapters in the book, Hunter suddenly fills it. In the middle of a crack binge, having not slept for days, a random couple at a pool decides he just has to meet their friend Melissa. Two decades younger, Melissa tells Hunter he is no longer a crack addict on their very first date. She commences to erase most of the contacts in his phone and commandeers his computer. Just days later, he proposes marriage

And that’s it — show’s over folks; there is no third act. Melissa talks to the Democratic presidential nominee on the phone, who thanks her for helping his son find love once again — which apparently is all Hunter needed to stay sober. Smash cut to credits.

In late-stage addiction, the odds of falling in love are pretty good — but the goods are usually fairly odd. While there’s no right way to get sober, “Beautiful Things” ends in what feels like a cliffhanger.

Full disclosure: I’ve been clean and sober for almost 13 years. The story about how bad things got and what I do to stay sober includes things my kids don’t need to know about yet. There are many near-relapses — including a time around year eight when I allowed a lover to replace my program of recovery. It includes staying sober after my sister committed suicide. Getting through it sober is the El Dorado here. And my sobriety is a commodity — something I can point to when someone else I know is having a hard time staying sober. It’s how we do it.

What’s missing in this beautiful wreck of a drunkalog is the rotating, ever-present cast of other characters in recovery.

People are pretty open about being in AA these days, even though it’s still against the traditions in Twelve Step recovery programs. The basic reason is that no one represents AA; the group exists to help people get clean and sober. One of the many reasons AA’s “maintain personal anonymity at the level of press, radio, and films” is because if you say you went to AA and then you get drunk, people will think it doesn’t work.

And while Hunter very clearly states that AA wasn’t for him, it does work for many people. And as every sponsor in AA says when talking to a newcomer who has an easier way than AA to get sober but keeps relapsing: “How’s that working out for you?”

What’s missing in this beautiful wreck of a drunkalog is the rotating, ever-present cast of other characters in recovery, helping Hunter help them and, with that, letting Hunter help himself stay sober. Hunter’s solution — relying on first Beau and then Melissa — is too fragile for the rough road people in recovery have to travel every day.

Our stories are our most valuable possessions; they have powers, like amulets, to ward off trouble and serve as guideposts for others. Hunter’s story is powerful. At some point, he will achieve a lasting sobriety, and make it his True North — or, like too many of us, he’ll die trying. I hope that doesn’t happen, because this book makes clear Hunter Biden has a lot to offer.