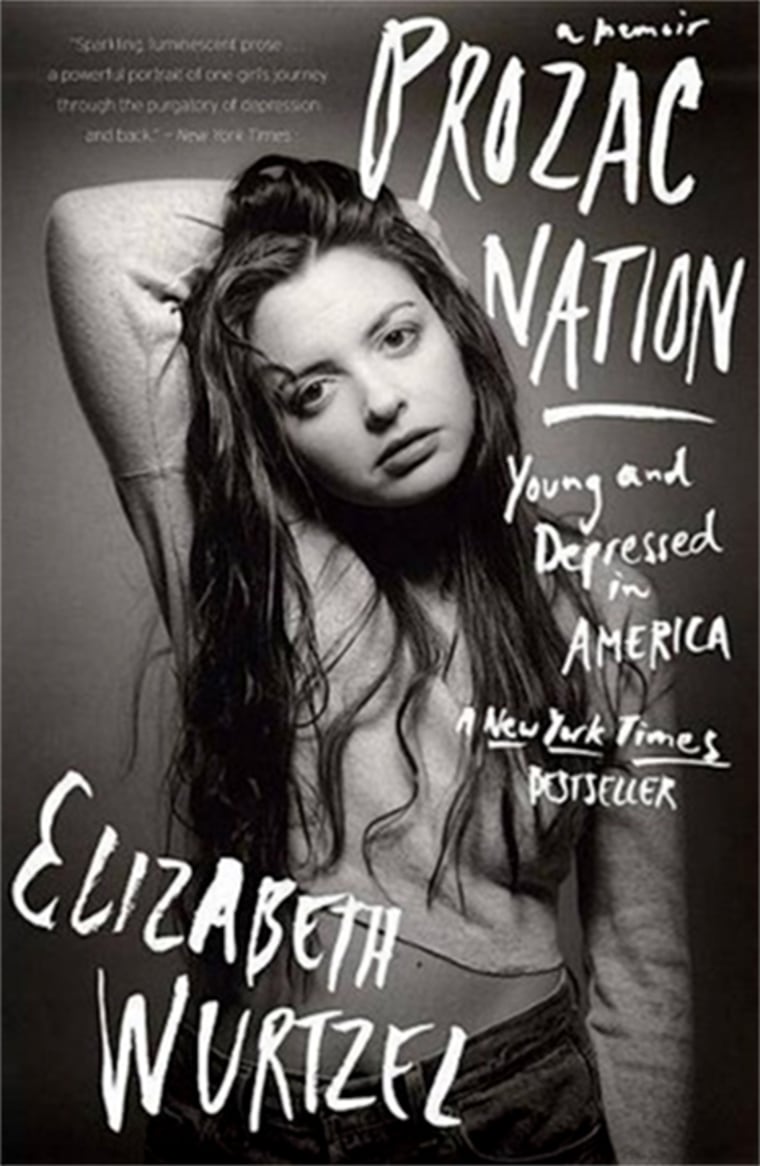

I was given the assignment of reviewing Elizabeth Wurtzel's "Prozac Nation" for a small weekly newspaper in 1994 by an editor who said something to the effect of “have at it.” Before reading it, the 23-year-old me didn’t know anything about the 27-year-old author, who was already an accomplished journalist and a rock critic. I had moved to a recession-ravaged New York City after graduating from Rutgers University just two years earlier with little more than one friend, two wide eyes, a blind faith and scattered ambitions, all of which landed me one egregiously underpaid publishing job after another.

I was on assistant job No. 3 — at HarperCollins — when I got the assignment. I was broke, unmoored and clinically depressed, and didn’t know where to begin to find a therapist, let alone medication to treat my depression. That is probably why I had such a visceral reaction to "Prozac Nation," with Wurtzel’s bold, naked evocations of longing and rage, and uncompromising descriptions of depression so acute that it led her to breakdowns and suicide attempts; the book sliced through me like a razor.

Part of me was jealous: Wurtzel described a seemingly enchanted New York City existence, with the kind of education and jobs, experiences and accomplishments I hadn’t even imagined the possibility of pursuing. I'd always been told that my fellow Gen-Xers were slackers (and had seen enough in media), but she was so industrious and accomplished even as my real-life peers and I were busting our butts, trying to hold on to jobs, scrambling to pay rent and bills and stay atop student loans. Mostly, though, I was cowed by her brave candor and her defiant voice; it demanded everyone's attention with such force, making us look at things we’d been socialized to compartmentalize, to turn away from, to outright deny.

I thought, reading her memoir, that I’d either love the crap out of her or be overwhelmed with exasperation, not realizing then that the two feelings weren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. Being a cavalier, petty 23-year-old, I un-cleverly and viciously panned "Prozac Nation," and quickly regretted it.

It was, you see, then one of two exciting new memoirs published by Betsy Lerner at Houghton Mifflin that would spark a literary zeitgeist (the other was "Autobiography of a Face," by the late Lucy Grealy). She was a rare young woman who took up space, commanded us to bear witness to what we’d later dismissively call "oversharing," seemingly unafraid to present herself on the page as what we, again, would later dismissively call "a hot mess" and, in doing so, she indelibly reshaped the memoir genre — the whole memoir genre, not just the women's memoir genre.

But her outsize literary influence wasn't the source of my regret. That came when, a month or so after my review, a mutual friend introduced us and I instantly loved her. As I'd suspected reading, I also soon found her to be intense and exasperating, but I loved those qualities about her, too.

There was no Google and no internet to out me as the author of one of her terrible reviews back then, but I became preoccupied by how and when to come clean about it. Before I could muster the courage, though, our mutual friend spilled the beans, relieving me of the guilt that had begun to cast a pall over our burgeoning friendship. I was mortified and truly sorry, but grateful it was out in the open. Elizabeth simply asked, “Do we need to talk about this?” and wondered whether I’d written it before or after we’d met. When she learned that it had predated our meeting, she forgave me.

I was reminded of both my review and her forgiveness Tuesday when I reached for my copy of "Prozac Nation" after being kicked in the heart by the news of her death from metastatic breast cancer, at the criminally young age of 52. It wasn’t the first time I’d revisited "Prozac Nation": A year after we’d met, I was in the grips of my own depression, exacerbated by the news of a close friend’s suicide months earlier.

Elizabeth came over to my tiny studio apartment in Park Slope, found my copy on my desk, picked it up and inscribed it. “Well, do you like this book better a year later?” she wrote. “Suffice it to say that of the many people who gave me bad reviews, you’re my favorite. I love you and am so glad we’re friends. Peace, love and snatchforce — FTW — Elizabeth.” ("FTW," which was tattooed on her shoulder blade, was not the modern day text message acronym “for the win” but one of her own, sometimes meaning “fight to win” but more frequently, its alternate: “f--- the world.”)

I did like the book better a year later. Actually, I more than liked it: I was ready to absorb her words, her stories, her rage, her humor, her longing. I was ready to allow "Prozac Nation" to resonate with me.

It had felt dangerous when I read it because genuine honesty is dangerous. At the time, many of us didn’t realize or fully appreciate how necessary it was for women of our generation to be loud, to be in your face or to testify. We were dismissed as slackers and losers, rendered invisible like middle children, burdened with debts and anxieties and responsibilities to our parents and future kids, caught between the 20th and 21st centuries. Elizabeth emerged as one of the most important voices for our generation — especially for those of us grappling with mental health issues — because she was able to demonstrate that in order to be heard, you have to demand that attention be paid to you, to your pain, to your generation’s battle scars.

She didn’t seek allies or apologies; as messy as she presented herself to the world, she was clear-eyed about who she was and what she needed. And so I loved it.

And I loved her, her intensity and loyalty, and the friends and experiences she generously shared with me. Her words and her friendship became life rafts for me during the worst and even best of times. Elizabeth and "Prozac Nation" gave me — and so many people of our generation, and even the next generation — a voice and, with it, a kind of road map forward.

About 15 years ago, we ran into each other at a book party after not having seen each other for a couple of years. She said, warmly but bewildered, “Oh, there you are!” as if we’d been momentarily separated, and she'd just been wondering where I'd wandered off to. But it was more than that: She’d enrolled in law school, I’d fallen in love with the woman I would soon marry — all the typical things you say about falling out of touch with people in your 30s.

But that didn’t mean I had ever stopped loving her or thinking about her. I continued to follow her through her potently honest writing in what I know now to have been her final years — not least of all, her pursuit to learn whether she carried the BRCA gene after her original breast cancer diagnosis, she discovered the truth about her father. And, her searing, fiery, breathtaking essay about having stage 4 breast cancer, in the Guardian, in which she, in essence, seals her legacy about who she is, as a writer, as a fighter, as a woman at the end of her life: “I don’t need you to be on my side — I’m on my side … I love being controversial, because that’s the closest you get to everyone agreeing with you — the other choice is no one is paying attention.”

I am gutted — I find it inconceivable, even — to have to consider that she’s not here to seize our attention.