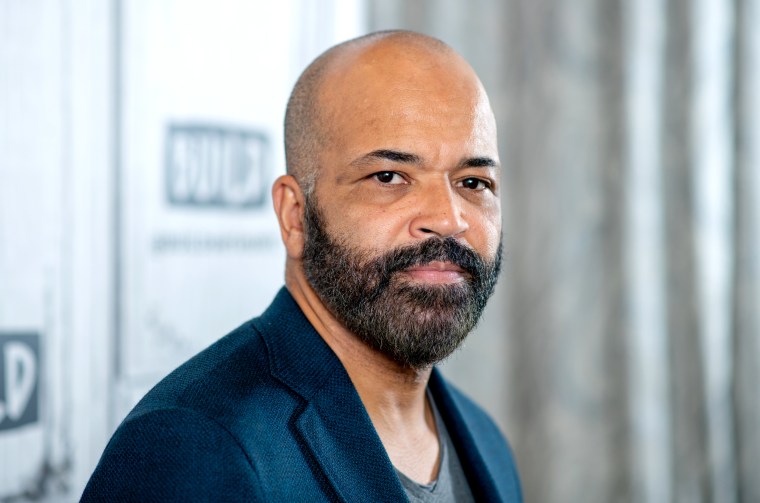

The transition from incarceration to reintegration into society is very much at the center of what our story is about in "O.G.": I play a man who's been incarcerated for 24 years, who is in the final weeks of his sentence. As a result, I had many conversations with folks on the inside, since we filmed in a working facility, and largely worked with men who are incarcerated in the roles of the other incarcerated men.

Almost to a man, they described what they feel is a universal period of anxiousness — of confusion — about what lies on the other side of the wall because, in many ways, time has stood still for them while they've been incarcerated, and the world outside has become foreign. But it's also because they've lived within an institution that has made every day-to-day social choice for them, and so their decision-making skills have really atrophied.

That's a real danger to someone who's reintegrating into society after having committed a serious crime, as the men that I worked with have. Reintegrating into society with your social skills having atrophied, but with your survival skills having been honed in a dangerous setting, is not necessarily the best combination for the general public, let alone for them.

They recognize that, too: I asked one guy, who had been in for 35 years, about this phenomenon very early on in the research process. He said, "Well, in here we have guards posted, they have cameras everywhere, so if I get into it with somebody, if we go at it, they're gonna stop me. If I get into it on the outside, who's gonna stop me?" It was a chilling confession to hear, because he was acknowledging his inability to govern himself; that has not been a part of the programming that he's been subject to while incarcerated.

For me, that was just another experience that reflected how well-informed these guys are about who they are, about the conditions that are endemic to incarceration and about the conditions that led them to incarceration. I think that, if legislators and prosecutors had access to the wealth of knowledge that these folks have in the way that I did, we could begin to form policy on a level that was much more preventative of criminality, preventative of violence and preventative of incarceration — if, in fact, that's our national intent.

Those guys have the answers; there's a universal theme that runs through their stories. Many of these guys checked off the identical boxes along the way: Parents who were negligent, perhaps drug addicted, which led to abandonment at an early age; on the streets by 10, 11, 12; involved in illicit activities once they're teenagers. They could each describe to me a chaotic story that led to their first case by 16 or 17, and to incarceration.

There were just these milestones along the way where, if we really pay attention to the kids out there now who are passing by those milestones, we can implement new policies to redirect them, and thereby do a lot more to decrease criminality and incarceration in our society.

One fix for me would be universal pre-K, because it's cheaper to educate kids and shape their minds and their aspirations at an early age than it is to incarcerate them for 40 years. It was evident with a lot of these guys that, in many ways, they were headed down this path by the time they were five years old.

Beyond that, I saw many men at Pendleton who were clearly trying to work through issues of mental health and doing it on their own for the most part. The most palpable sensation on the inside of that prison was trauma: The trauma that these men had delivered onto others, but, also, the trauma that they had gone though early in their lives was so evident. And I often encountered men — though not always — who were actively trying, with very little means, to address that trauma, to repair that damage and to create better selves and ideally better citizens.

But the guys in Pendleton are inside a system, in an institution, that is probably the least healthy environment for someone who suffers from mental health issues like post-traumatic stress disorder. That doesn't seem like a smart policy for the state of Indiana or any other state, especially because not all of them are in there for life.

If you view everyone who in incarcerated as undeserving of that treatment, or if you view them as only deserving of punitive measures, then it's almost understandable to have no help for them, but it's still not good policy. If we look at the situation in a more holistic way, in terms of the health of our society, we should probably reconsider our general perspective on what incarceration means.

We need to ask ourselves whether incarceration is rehabilitative, or whether it is purely about punishment — and about us, as citizens, in some way tacitly enjoying the state's punitive power. I think that some of us enjoy the state using its power in that way, or even feel somehow that's representative of justice.

I had the sense that most of the people who are incarcerated come from impoverished neighborhoods, both rural poverty and urban poverty. From a policy perspective, it feels like we didn't care about them before they got in there, so it makes it even easier for us to exert punitive power, as opposed to rehabilitative, once they've committed crimes. And when they're behind bars, we turn our backs to them entirely. Perhaps, we'd just as soon turn our backs to them anyway.

As told to NBC News THINK editor Megan Carpentier, edited and condensed for clarity.