Iranian Gen. Qassem Soleimani, head of the Revolutionary Guards’ feared Quds Force, was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of U.S. and allied troops. He personified values deeply at odds with those of the international community. He was a combination of senior military leader and regional political figure, a totem of his regime and a convener of terror operations. Several strong arguments can be made as to why he deserved to die. But does that mean the United States was wise to kill him on Friday?

3rd century Rome was a hotbed of attempts to kill emperors, most of them failures, that seriously degraded the empire’s ability to fight off threats — in particular from Persia.

Assassination has a long history in foreign policy and military affairs: on occasion, the surprise killing of a single individual can advance a cause or achieve a valuable military objective. But assassinations are a literal hit-or-miss undertaking: the target often escapes, and unintended consequences can mean a killing goes awry in other ways.

That makes it a risky, and sometimes reckless, tactic that U.S. presidents long tried to limit before the war on terror changed their calculus — a reversal that hasn’t endeared the United States to the international community or provided much sense of security for Americans. While U.S. advances in remote-controlled military capabilities, and its status as the sole superpower — largely protecting it from major retaliations on American soil — make targeted killings of high-level leaders an increasingly alluring tool, the Soleimani assassination may provoke a rethink, and could shift opinion in Washington away from assassinations in the future.

The problem of botched assassinations and unpredictable fallout isn’t new. Both Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolf Hitler were the subject of multiple attempts on their lives, none of them successful. Russian Czar Alexander II’s murder in 1881 only came after several unsuccessful efforts; and 3rd century Rome was a hotbed of attempts to kill emperors, most of them failures, that seriously degraded the empire’s ability to fight off threats — in particular from Persia, the empire whose modern-day descendant is Iran.

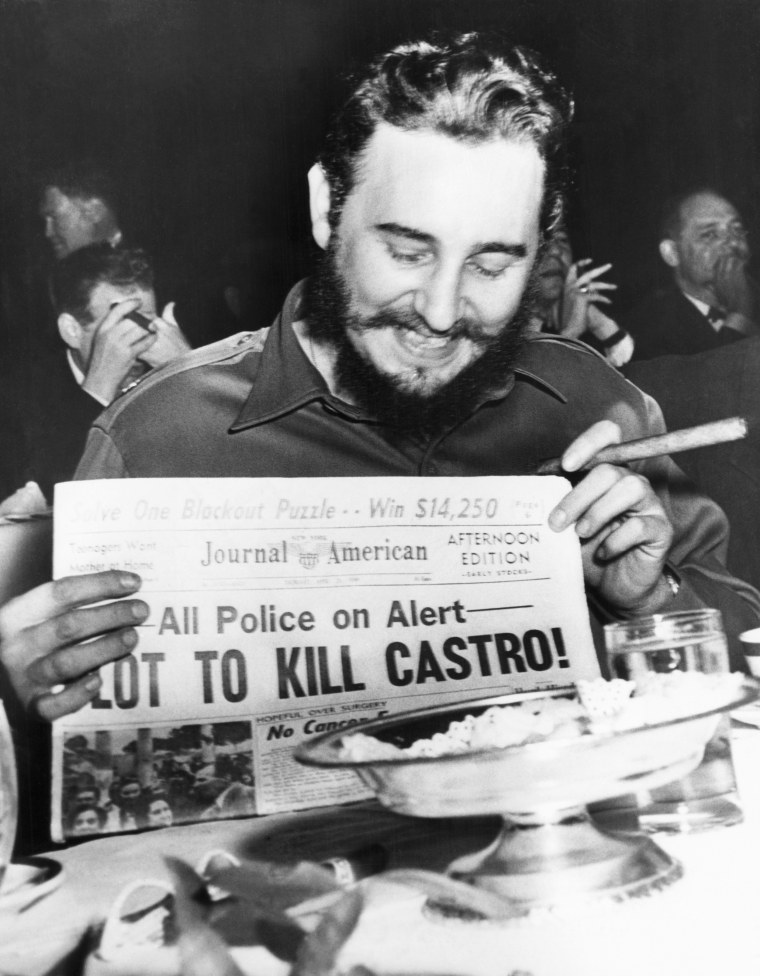

The U.S. has suffered its own misfires and humiliations in historic assassination attempts, most notably when President John F. Kennedy sanctioned numerous operations to kill Cuban communist leader Fidel Castro. These included cigars poisoned with botulism, exploding cigars and hypodermic syringes loaded with toxins and hidden within ballpoint pens. Castro’s former lover was approached to kill him, as were mafia hitmen. All the attempts failed, with each blunder bringing more ridicule and boosting Castro’s esteem.

That experience was a major factor in executive orders issued by a trio of subsequent presidents — Republicans Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan and Democrat Jimmy Carter — severely curtailing U.S. state-sponsored assassinations. In addition to the Castro misadventures, the U.S. was also implicated in a spate of highly controversial attempted and successful killings in the 1950s and the 1960s, often linked to the Cold War. These included the executions of Congolese President Patrice Lumumba in 1961 and Ngô Đình Diệm, president of South Vietnam, in 1963.

Yet even when the assassins hit their mark, as in these two cases, the outcome wasn’t necessarily desirable for Washington. The killing of Lumumba gave moral strength to his cause and led the U.S. to be cast as an enemy of the independence movement in Africa. The killing of Diệm led to the much-enhanced, and much-maligned, American military presence in Vietnam.

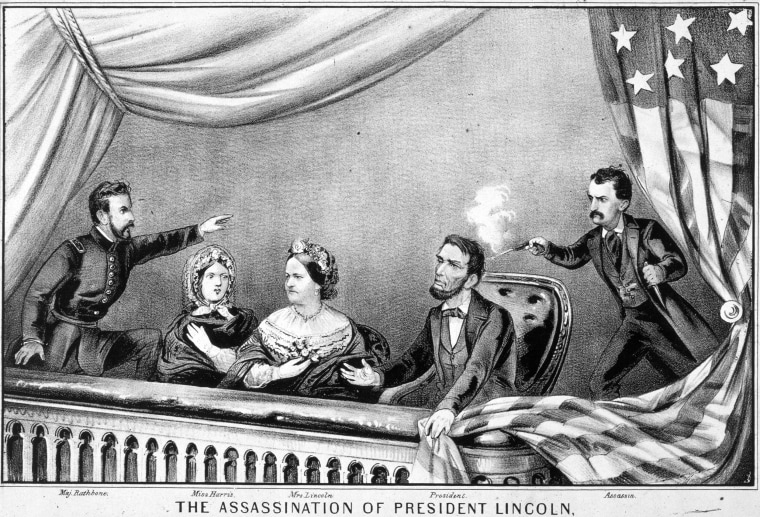

Indeed, high-level assassinations often bring about results that undermine their initial objectives. One compelling example stems from an American leader’s death: President Abraham Lincoln, whose killing had a complicated effect on the former Confederacy — in particular on the South’s Reconstruction — very different from the one sought by his assassin, John Wilkes Booth. More recently, the 1914 killing of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the 1948 assassination of Mohandas Gandhi in India both preceded geopolitical chaos and bloodletting on an epic scale.

The U.S. would also do well to remember that some of the most tragic unintended consequences of high-level assassinations include reprisals. Following the 1942 death of Reinhard Heydrich, a leading Nazi and architect of the Holocaust, Hitler order a revenge killing of Czechoslovakian citizens on a mass scale. Some 5,000 innocent men, women and children were executed, and the village of Lidice, mistakenly thought to have harbored the assassins, was eradicated.

Another lesson for the Trump administration to keep in mind is that assassinations can tarnish the reputation of those who conduct them. Vladimir Putin’s Russia was quite rightly ostracized for its attack on Russian agent-turned-British refugee Sergei Skripal and his adult daughter two years ago — including for their reckless use of a nerve agent whose remnants killed an unrelated British woman three months after the failed assassination attempt. More than 300 Russian diplomats were expelled from around the world in response, uniting opposition to Moscow.

Despite these pitfalls, the U.S. never abandoned the use of assassinations entirely. In 1986, following a naval incident in which Libya attacked U.S. ships in the Mediterranean and then sponsored a bomb attack in Berlin that killed two U.S. servicemen, Reagan ordered an airstrike on Libya that came close to killing Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi.

And in August 1998, following lethal bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, President Bill Clinton ordered a carefully targeted strike on al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden — another failed assassination.

But the incident does show that assassinations aren’t always unwarranted or unproductive; there can be cases in which selective killing can prevent great harm. Intelligence suggests Clinton was probably correct that, had bin Laden been killed, the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, would have been prevented.

Ironically, one upshot of that terrible day was to put assassination back into the mainstream of national security options, at least when dealing with unreconcilable terrorists intent on inflicting harm on the U.S. and its allies. Combined with advances in surveillance and drone technology, the use of targeted killing became a major instrument in the war on terror, initiated by President George W. Bush and continued by his successors in the White House.

President Barack Obama, for his part, sanctioned more than 500 such strikes on top terror leaders down to foot soldiers. Most famously, he finally succeeded in overseeing an operation to hunt down and kill bin Laden in Pakistan in 2011, which not only took out a weakened but still vital linchpin in a top terror organization, but also allowed for the collection of troves of intelligence that prevented future attacks. A similar benefit came from the elimination of Islamic State militant group leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October, setting back another global terror outfit.

The grim record of assassinations shows that sometimes they can achieve valuable objectives, but they are much less likely to achieve the desired results.

But bin Laden and al-Baghdadi were arguably the most successful assassination targets in recent American history because they were the head of terror networks without any affiliation to a recognized state. As such, the legal case for killing them was relatively straightforward, and the risk of consequences — both in terms of triggering retaliation but also stoking regional tensions — more limited. Compared with this week’s assassination of Qassem Soleimani, very few objections from the international community were raised following the killing of either bin Laden or al-Baghdadi.

The grim record of assassinations shows that sometimes they can achieve valuable objectives, but they are much less likely to achieve the desired results — and only the desired results — when targeting a senior government figure affiliated with a robust military power. Even when they are conducted selectively, legally and strategically, history suggests they can still turn out to be unwise.