On Wednesday afternoon, the Milwaukee Bucks did not come out of their locker room for Game 5 in their first-round playoff matchup against the Orlando Magic. In a historic decision, the team refused to go out and play. A few days earlier, a white police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a town roughly 40 miles from Milwaukee, shot Jacob Blake, a Black man, seven times in the back at close range as Blake was getting into a car. Blake’s children were in the back seat. His family says he is now paralyzed from the waist down.

They revealed how emotionally, mentally, and physically sick and tired Black people — athletes included — are of the violence, the videos, the hashtags, the rinse and repeat of this cycle.

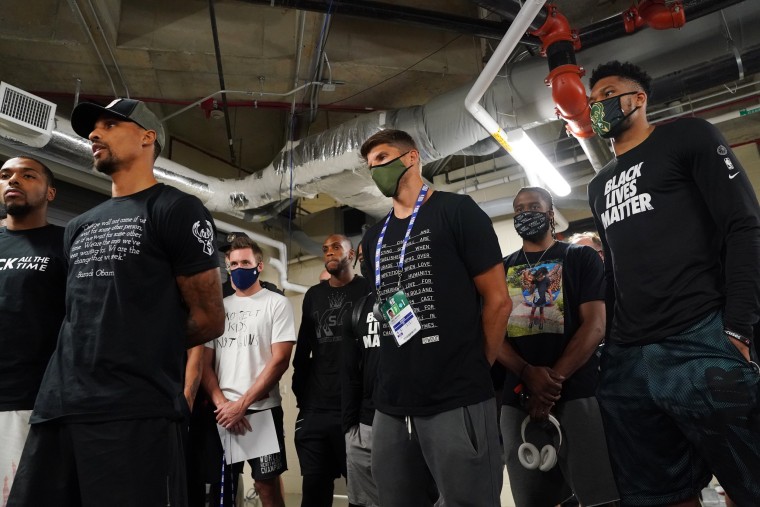

The Bucks players explained that on the court, they “are expected to play at a high level, give maximum effort and hold each other accountable” and they want that same standard applied to lawmakers and law enforcement. They want “the Wisconsin state Legislature to reconvene after months of inaction and take up meaningful measures to address issues of police accountability, brutality and criminal justice reform.”

Then the dominoes started to fall. First the players from the other four NBA teams scheduled to play Wednesday walked out, followed by the Milwaukee Brewers and other teams and players in Major League Baseball, the athletes in the WNBA, players in Major League Soccer, and grand slam tennis champion Naomi Osaka. They joined the Bucks in solidarity, sending a message against racist violence. They revealed how emotionally, mentally and physically sick and tired Black people — athletes included — are of the violence, the videos, the hashtags, the rinse and repeat of this cycle. And all against the backdrop of a major health pandemic that has disproportionately hurt communities of color.

This walkout of professional athletes is frankly unprecedented. There is a lot of money on the line here, as leagues have made clear in their push to return to play after the pandemic shut everything down. Back in March, the NBA feared it could lose $1 billion. And there is always the backlash that individual athletes have to weather, especially Black athletes, when they protest. It’s no surprise that we’d never seen anything quite like what happened on Wednesday evening.

At the same time, this moment feels somehow inevitable, as if there was no other possible outcome. This moment did not spring forth, fully formed, out of a vacuum. Athlete activism has a long history, as does protest against racist police violence. This activism stretches back decades, but the momentum building over the past seven or so years has reached an inflection point in 2020. It has been the professional basketball world, in particular, that has led the way.

In 2012, Miami Heat players, including LeBron James and Dwyane Wade, donned hoodies and posted the picture and hashtag #WeAreTrayvonMartin. #BlackLivesMatter was founded in 2013, after Martin’s killer George Zimmerman was acquitted. That same year, WNBA player Tierra Ruffin-Pratt’s cousin was shot and killed by an off-duty police officer.

In 2014, five St. Louis Rams took to the field before a home game with their hands in the air, modeling the “hands up, don’t shoot” gesture protesters in nearby Ferguson, Missouri, were using after the death of Michael Brown. That same year, players on the L.A. Clippers silently protested racist remarks by then-owner Donald Sterling, and NBA players around the league wore “I Can’t Breathe” warm-up shirts after an officer using a chokehold killed Eric Garner in New York.

In 2015, NYPD officers broke the leg of the NBA's Thabo Sefolosha, then with the Atlanta Hawks and now with the Houston Rockets. He sued, and the city eventually paid him $4 million.

Before quarterback Colin Kaepernick began protesting police brutality in the NFL preseason in the summer of 2016, the Minnesota Lynx wore shirts with the phrases “Black Lives Matter,” “Change Starts With Us — Justice and Accountability.” They honored Philando Castile, Alton Sterling and Dallas police officers killed while on duty. Other WNBA players joined in and — after the league fined the players — they continued their protest, refusing to answer any press questions about basketball. Eventually the WNBA rescinded the players’ fines.

Kaepernick started his protest on Aug. 26, 2016 — four years to the day before the Bucks stayed in their locker room. Soccer's Megan Rapinoe then began kneeling in solidarity with Kaepernick. More NFL players took knees or raised fists, but Kaepernick was gone after that season, blackballed from the league.

In 2018, Sterling Brown, a Milwaukee Buck and one of the players who read the Bucks’ walkout statement on Wednesday night, was aggressively questioned by police officers in Milwaukee for parking across two handicap spaces in an empty Walgreens parking lot. In early July, for the Players Tribune, Brown wrote, “The city of Milwaukee wanted to give me $400,000 to be quiet after cops kneeled on my neck, stood on my ankle, and tased me in a parking lot.” He didn’t take the money and instead told his story.

Maya Moore, at the height of her basketball career, left it all behind to advocate for Jonathan Irons, a man she felt was wrongfully convicted. He was recently released from prison, in large part due to Moore’s work.

Then COVID-19 hit. A few months after America’s cities shut down in response to the pandemic, Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer, kneeled on the neck of George Floyd, a Black man, killing Floyd. Protests against racist injustice took place in every state and in multiple countries. Athletes spoke out and participated in those protests. Kylin Hill, a running back at Mississippi State, successfully led the push to remove the Confederate flag from the Mississippi state flag. Bubba Wallace finally got NASCAR to ban the Confederate flag from its events. Two softball teams quit after the general owner of one team bragged on Twitter to Trump that the players stood during the national anthem. College athletes asserted their voices as schools put pressure on them to return to play.

When professional leagues decided to return, some players, like the WNBA's Natasha Cloud and Renee Montgomery and the NBA's Wilson Chandler, decided to skip playing this season to focus their attention on their communities.

The WNBA players, as a group, decided to honor Breonna Taylor, a Louisville woman killed in her own home by police officers, by wearing Taylor’s name on their jerseys and dedicating the season to her and other Black women killed by law enforcement (#SayHerName). When the co-owner of the Atlanta Dream, Kelly Loeffler, a Republican U.S. senator running for re-election, spoke out against the Black Lives Matter movement and the league, the players wore shirts supporting her opponent.

The NBA wrote “Black Lives Matter” on the court and players could choose from a set list of phrases pre-approved by the league to wear on the back of their jerseys.

As Kavitha Davidson and I write in our new book, “Loving Sports When They Don’t Love You Back,” which has a chapter on athlete activism and the politics of sports, “beginning in the early 2010s, and continuing today, we are witnessing a new wave — some might say an avalanche — of athlete activism.” Still, we weren’t sure if that wave would fizzle out before reaching land or crash on the shore. We know now. It’s crashed.

On Tuesday, L.A. Clippers coach Doc Rivers, responding to the police shooting of Jacob Blake, said: “It's amazing why we keep loving this country, and this country does not love us back. It's really so sad. Like, I should just be a coach. I'm so often reminded of my color. It's just really sad. We got to do better. But we got to demand better.”

The next day, in an extraordinary move, the Bucks demanded exactly that.