It was so easy to hate on Mac Miller, at first. It was easy to deride him for his slackjaw and glazed expressions, his ostentatious tattoos, elementary rhyme schemes and clichéd lyrical content. Many dismissed him as a frat bro, a culture vulture, a lethargic Eminem knockoff.

This hostility was evident from the reaction to the white Pittsburgh rapper's first album, “Blue Slide Park,” released in 2011. “He's mostly just a crushingly bland, more intolerable version of Wiz Khalifa,” Pitchfork wrote; Spin called it “what would happen if the cast of Glee tried to make a rap album.”

But while Miller (real name Malcolm McCormick) could have faded into laughable obscurity like many of his early peers, from Asher Roth to Chiddy Bang to Far East Movement, something strange happened. His rhyme schemes got knottier, his lyrics became more probing. His production grew layers. His live performances gained snap and texture. Each album he released was better than the last, up through his fifth album “Swimming,” which came out in August.

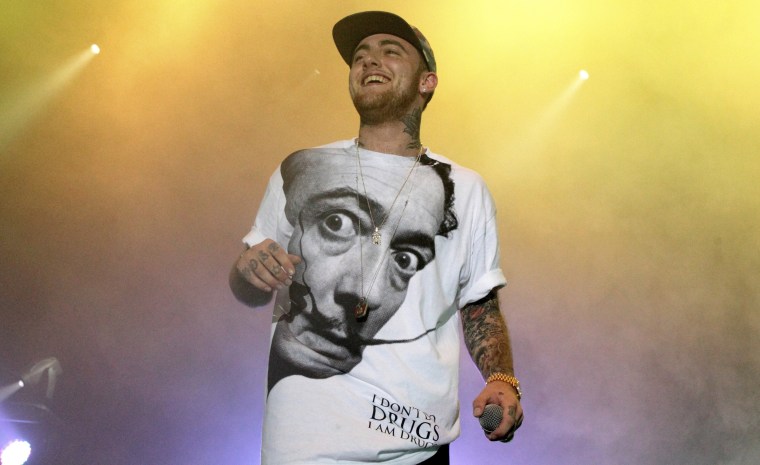

Mac Miller was preparing to embark on a headlining, cross-country tour when he died on Sept. 7 of a suspected overdose. He was 26. His continual progress in many facets — in music, as a mentor and as a person struggling with addiction — makes his death all the more crushing.

Miller could easily have taken a different path in the wake of “Blue Slide Park.” Considering its critical contempt and commercial success — it went number one on the Billboard 200 — he could have simply replicated the formula and enjoyed a comfortable if cookie-cutter career, full of bland motivation and cheesy excess.

But instead, Miller stayed with his independent label — the Pittsburgh-based Rostrum Records — and diligently honed his craft, embedding himself within an indie rap scene that was exploding in pockets across the country, from Kendrick Lamar in Los Angeles to Chance the Rapper in Chicago to Joey Bada$$ and ASAP Rocky in New York. Over the next two dizzyingly prolific years he would write hundreds of songs and release five projects.

Meanwhile, collaborators like Lamar, Tyler the Creator, Vince Staples and Jay Electronica helped him push his lyricism to new heights. His verses ranged from the philosophical to the uproariously crude to the shockingly personal — especially when he opened up about depression and his addiction to prescription opiate cough syrup.

While his biggest hooks still provided the soundtrack to many a kegger — like the defiant “America” or the braggadocious “Donald Trump,” which he has since apologized for — Miller also explored impulses that were increasingly dark, abstract and introspective. One of his lyrical peaks was an uncredited appearance on Earl Sweatshirt’s 2013 song “Guild.” While Sweatshirt himself is known for his technical wizardry, Miller more than matched his virtuosity with a minute-and-a half long marathon filled with sullen revelations, loopy non sequiturs and relentless internal rhymes: “This a hit of liquid heroin / Marilyn Manson channeling / Panicking, spar with Anakin / 'Til one of us leave in an ambulance.”

Miller wouldn’t be boxed into just rapping, either. On his second album, “Watching Movies With the Sound Off,” he turned to production, creating most of the album’s psychedelic beats under his alias Larry Fisherman; he would later produce songs for SZA, Ab-Soul, Riff Raff and other innovative artists. A 2014 episode of Mass Appeal’s “Rhythm Roulette” offers an incisive look at his all-encompassing creative process: Miller wades into the jazz section of a record shop, pulls unintuitive, polyrhythmic samples out of the music and records bass, piano and 808 drum machine parts to pull the disparate elements together into a texturally fascinating whole.

His exploration and affinity for jazz would seep into his most recent two albums, “The Divine Feminine” and “Swimming,” which drip with delicate piano runs, springy basslines and elastic drum pockets that perfectly compliment his plaintive and melodic voice. In an NPR Tiny Desk concert from last month, Miller sits next to the omnipresent and fleet-fingered bassist Thundercat; his face watching the bassist’s convulsive runs with what can only be described as joy.

Despite his age, Miller was also notably big-hearted. Throughout his career, he lifted up those around him: he took Chance the Rapper on tour when the Chicago emcee was just getting started and mentored a younger generation that includes Post Malone and Lil Yachty. Politically, he was a vocal supporter of #BlackLivesMatter and spoke openly about white privilege. Since his death, remembrances have been pouring in about his quiet generosity, like when he foot the bill for an entire dinner party.

Still, Miller fought a continuous battle with addiction and destructive habits. He hit a nadir in May when, following his public breakup with pop star Ariana Grande, he drove his car into a pole and was arrested on charges of driving under the influence.

“I needed that,” he said in a radio interview this summer. “I needed to run into that light pole and literally, like, have the whole thing stop.”

“Swimming” doesn’t shy away from these difficulties. It deals in heartbreak, disillusionment and betrayal. But Miller also resolutely offers glimpses of hope, etching a portrait of a man who was constantly working to better himself: “And I was drowning, but now I'm swimming / Through stressful waters to relief.” He will be missed.