Organizing guru Marie Kondo has built a multimillion-dollar industry by urging people to ask themselves whether each object they own “sparks joy”— and if the answer is no, to discard it. But that’s a difficult exercise for a person like me with multiple identities: refugee, first-generation Vietnamese American, daughter, mother, writer and family historian. Strictly following Kondo’s advice during the spring cleaning push to purge one’s home raises the risk of making decisions that diminish one’s family history and cultural memory.

Kondo’s approach focuses on our present joy in objects, rather than our past or future. But what we think we know about ourselves today vis-à-vis our possessions is incomplete, even erroneous, given that this knowledge evolves with time as our own identities shift. And making hasty judgments to throw things out may cause us future regret, as well as regret on the part of our descendants who might have found their own joy in these items.

What we think we know about ourselves today vis-à-vis our possessions is incomplete, even erroneous, given that this knowledge evolves with time.

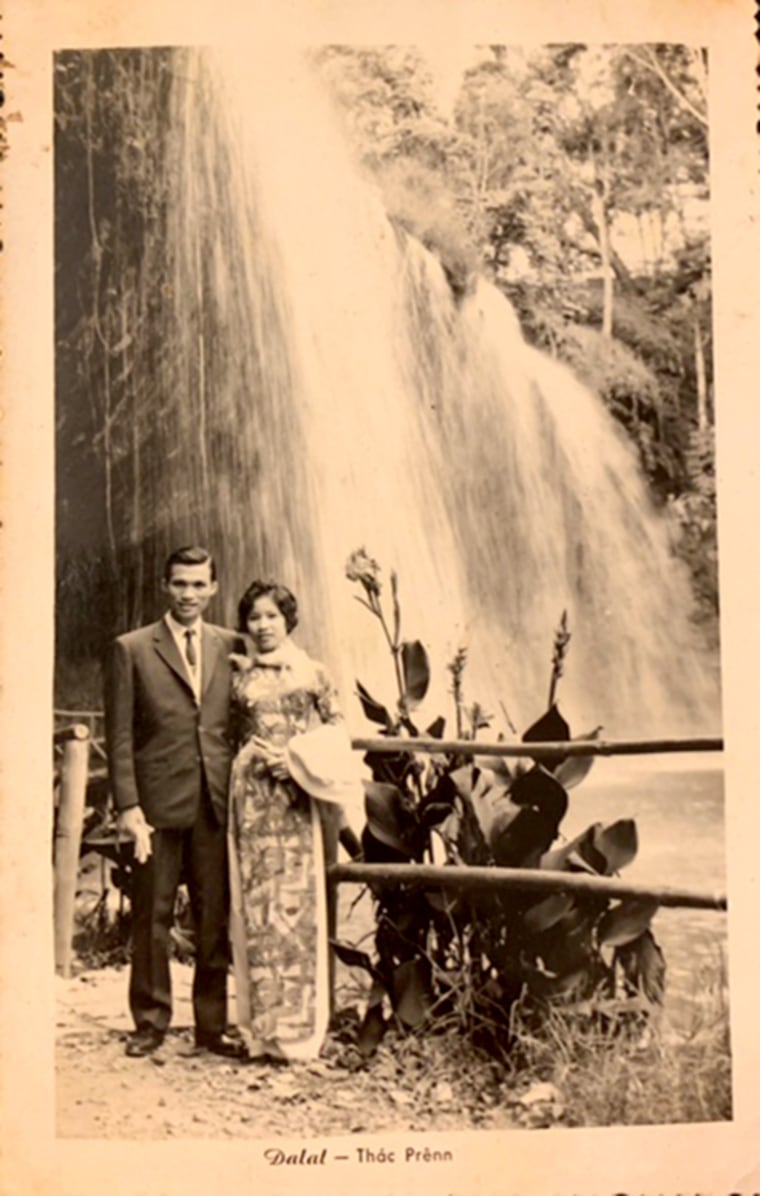

My family and I fled Vietnam 10 days before the fall of Saigon in April 1975, when I was 13 years old. My grandfather had worked as an interpreter for the U.S. Army, and the American officials who arranged for our departure told us to leave everything behind except what we could stuff inside a 6-by-12-by-14-inch traveling bag. My mother chose to bring the family photographs, three of her favorite ao dai — traditional Vietnamese two-paneled silk dresses — and love letters from my father. These objects were light in weight, but for my mother they evoked an entire universe: when life had seemed prosperous, immutable and safe.

A few years after settling in Virginia, though, she decided to give away her ao dai. She was not thinking about their historical significance to future generations, but how they painfully reminded her of the “irrelevant past” at a time when she and my father, then resident aliens of the U.S., had to work at low-income jobs to help feed a family of eight. Her once-youthful vision of the idyllic life must have saddened and embarrassed her, and out went those beautiful dresses.

Of course, “beautiful” might be my own wistful take on the past. My mother simply said that at some point the ao dai became “incongruous” with her American lifestyle. Her feelings about her clothing changed with time, as she herself changed. Indeed, something once cherished may later become an unpleasant reminder of our misguided aspirations; vice-versa, objects that spark shame at a particular period may trigger an epiphany years down the road. In deciding whether to keep an object, we are faced with either submitting to a burdened past or erasing the nucleus of some future revelation.

As displaced persons, our relationship to material possessions is also defined by our transplanted status and by historical forces, which keep us in flux. Assimilation is a process of editing one’s identity through space and time. Many immigrants believe that objects acquired in America are better than things from the old country. I had an Indian roommate in college who thought polyester was “fancier” than her old dresses made of Indian cotton, which she herself had discarded shortly after moving to the U.S.

Even if we decide to retain certain objects as keepsakes for future generations, though, there is no guarantee that our descendants will understand their significance. They need some memorializing context, especially if the objects in and of themselves “speak” nothing that can emit joy or excitement.

My mother still keeps, for example, my brother David’s Boy Scout uniform circa 1976. I had never thought of it as an important item, until she told me how happy my brother had seemed wearing it during the early years of our resettlement, enjoying the outdoors and adjusting well to his elementary school. His successful integration into American life has been my mother’s vicarious joy. She retains my brother’s uniform as a talisman.

We can’t retain everything, obviously. The act of tidying up, of editing and cataloguing a refugee’s life, requires a balancing act between the seemingly cohesive flow toward assimilation and the messiness of memory. Historical preservation calls for an in-depth inquiry into the objects’ purposes, their links to a person’s biographical timeline or family background, and the perceptions of the next generation toward them. Which of the things left behind are meaningful artifacts? Are their conservators equipped with sufficient sensitivity, knowledge and physical resources to undertake the preservation effort?

Ultimately, Marie Kondo’s approach works better if a more nuanced, less literal interpretation is applied. Her advice, by centering our experience in the present, at once acknowledges life’s impermanence and its potential for renewal. Tidying up, like the Beatles song, is about saying goodbye and hello. We have to trust that the things we give away, even in our imperfect knowledge, are not “lost” but continue to generate meanings to the other lives they enter while remaining latent narratives in our own subconscious.

The act of tidying up, of editing and cataloguing a refugee’s life, requires a balancing act between the seemingly cohesive flow toward assimilation and the messiness of memory.

Though I might mourn my mother’s decision to throw out her ao dai, I think she got the balance right when it came to shedding our first house in America — a 1950s rambler that we bought in 1978, our third year in the U.S. Though my dad lovingly planted hybrid tea roses in the front yard during the years of our American upbringing, one rosebush for each child, my mother hated the house, not least because it had intimately witnessed our transient, fresh-off-the-boat status.

Over time, the structure’s mid-century shabbiness could not accommodate her children’s physical growth or our family’s progress. We eventually succeeded in moving out, after the house was purchased by the county government so it could be torn down to make room for the Springfield Metro Line. My mother was overjoyed by this development, which she deemed divine intervention.

Days before the house was slated for demolition, she went back to uproot the rosebushes and transplant them to her new home.