We live in a time when the American government encourages us to “see something, say something.” But, increasingly, it feels to people of color like being seen by white people means having the police swiftly called on us, because we make those white folks feel uncomfortable based on our presence alone. What they’re “seeing” is people of color in spaces they expect to be more white, and they’re calling law enforcement to reassure them of that — and it’s blatant racism.

The latest example to make the national news (after two African American men were arrested at a Philadelphia Starbucks, an African American former Obama administration official faced down the cops as he attempted to move into his New York City apartment, and three African American women were pulled over by police after they checked out of an AirBnB in California because neighbors called the cops in the belief that the women were stealing) is two Native American teen brothers. Last week, while they were on a tour of Colorado State University — their dream school — a white mother on the tour called campus police because they were “real quiet,” and she said, Mexican.

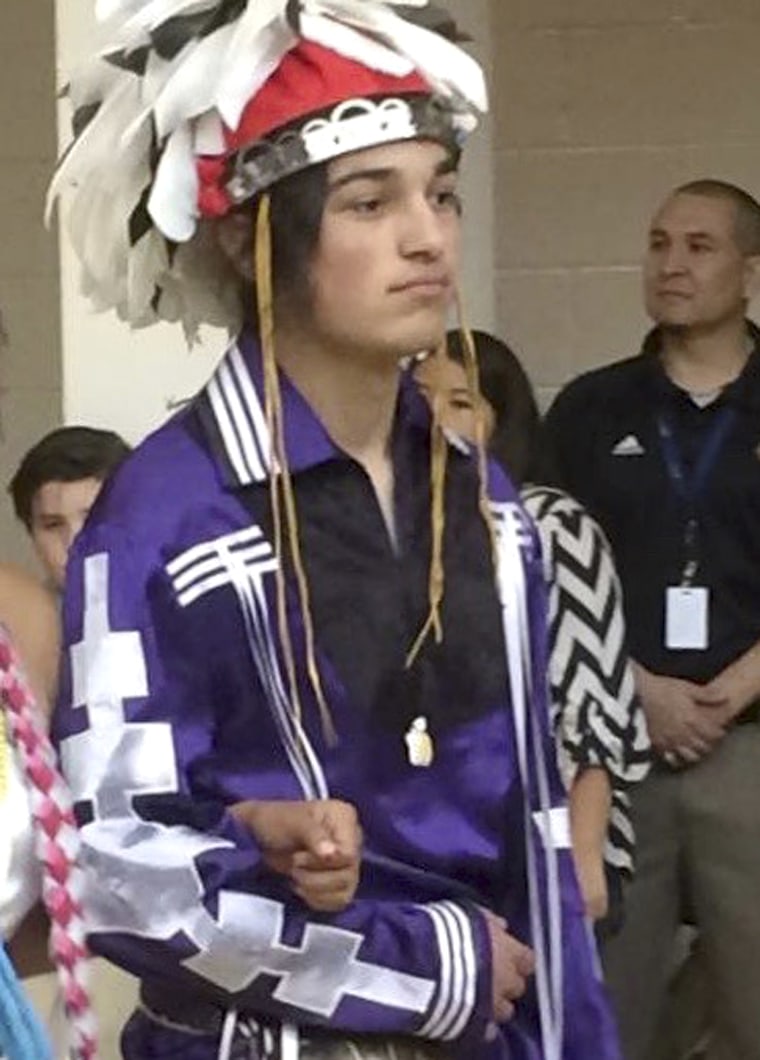

The two Native youths — Thomas Kanewakeron Gray, 19, and Lloyd Skanahwati Gray, 17 — traveled for seven hours to get to Ft. Collins, Colorado, with money they saved to make the trip, only to show up late to the tour and face that old-fashioned American racial profiling and a frisking by a pair of cops.

A woman, described in the police report as a white, blond parent who was along for the tour with her own son, called police on Thomas and Lloyd and told a 9-1-1 dispatcher that the boys made her “feel sick” because they were “real quiet.”

The only thing “sick” here is the unidentified woman’s haste to racially profile two teens of color on a tour of a college campus.

But of course, it is not that the Gray brothers were “real quiet,” it’s that they were “real quiet” and are not white: If the two were “real quiet” and white, it’s difficult to believe that the woman would have called the police.

Amid President Donald Trump’s ongoing threat to build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico, his attempt to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (currently blocked by the courts) and his recent order to end temporary protected status for hundreds of thousands of Hondurans, Nicaraguans and El Salvadorans, many of whom have lived here for decades, Americans tend to forget something fairly simple: Mexicans are also indigenous to this, our ancestral continent, and the establishment of a national border between the U.S. and Mexico — or some wall — does not make us all any less indigenous.

But the tired, centuries-old discrimination and demonization of indigenous people south of the border, as well as those living north of the border, continues, regardless of whether one’s Mexican or Native American like the Gray brothers, who are citizens of the Mohawk nation from the northeast United States. In my own experience, as an Oglala Lakota and Chicano, I have been told on numerous occasions to both “go back to the reservation” and “go back to Mexico.”

There is also a snippet of the woman’s call to police that is even more curious: “It’s probably nothing,” she said in a whisper. “I’m probably being completely paranoid, with just everything that’s happened.”

I wonder if by “everything that’s happened” she meant the white guy who shot and killed four people at the Waffle House in Tennessee? Or maybe the white guy who shot and killed 59 concert-goers in Las Vegas? Or maybe the white guy who shot and killed nine African-Americans in a church in Charleston, South Carolina?

Increasingly, it feels to people of color like being seen by white people means having the police swiftly called on us, because we make those white folks feel uncomfortable based on our presence alone.

Given “everything that’s happened” lately, the caller should have instead kept a sharp eye out for the quiet white people.

In response to the incident, CSU President Tony Frank said the situation was “sad and frustrating” and that he wants to offer the Grays a “VIP tour” of the campus. He added that the university will change its protocol to require campus police to notify tour guides if they need to pull anyone from their groups, The Associated Press reported and possibly offer all tour members identifying badges or lanyards.

“The very idea that someone — anyone — might ‘look’ like they don’t belong on a CSU Admissions tour is anathema,” he said in a statement. “People of all races, gender identities, orientations, cultures, religions, heritages and appearances belong here.”

Yet, according to the American Indian College Fund, only 14 percent of Native Americans have a bachelor’s degree, which is all the more reason why Natives should be treated fairly, with respect, and made to feel welcome at colleges and universities (and everywhere else for that matter), and not stopped and frisked.

It’s been a while since 1492, but from an indigenous lens, little has changed with regard to America’s fear of Native Americans, which is manifested today in police brutality in our communities, perpetuated by racist Indian mascots and, most recently, demonstrated in the discrimination of two Mohawk youths who frightened a white woman simply because they have pigmentation, showed up late, and were “real quiet.”

Simon Moya-Smith is an Oglala Lakota and Chicano journalist. His new book, “Your Spirit Animal is a Jackass,” published by Minnesota University Press, will be available Fall 2018.