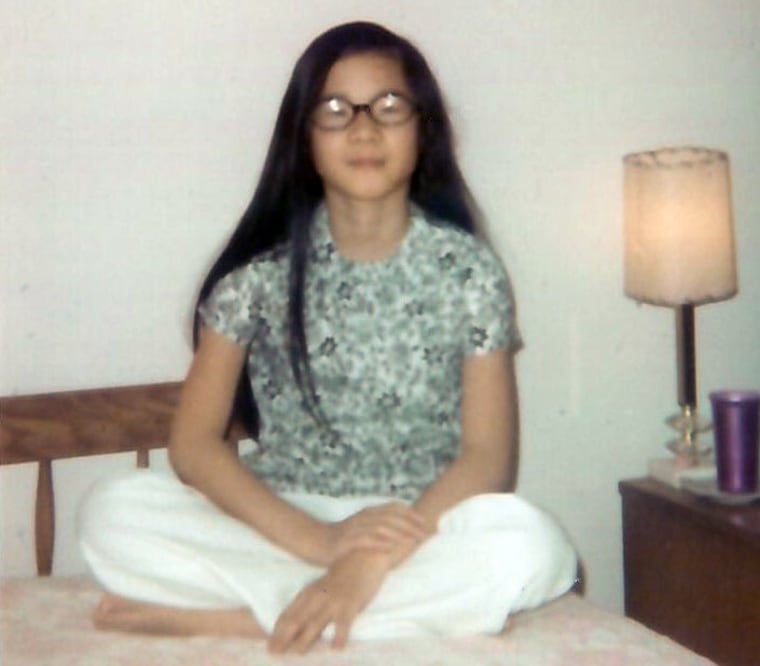

Relaxing on my bed in suburban Detroit, I was absorbed in yet another escapist novel from the library when my mother suddenly barged into my room. Her face was filled with a familiar madness as she grabbed my arm and dragged me toward the full-length mirror in the master bedroom. She had shears in one hand as she screamed hysterically and began hacking away at my waist-long hair.

It was the 1970s, I was 13 years old, and like most teenage girls of that time, I had faithfully grown my hair long to look like celebrity idols of the day. I sobbed as clumps of my shiny black hair fell to the floor.

She had shears in one hand as she screamed hysterically and began hacking away at my waist-long hair.

Mom grabbed a patch of the hair that people had called “black silk” and shrieked, “Frame this for memory.”

Decades later, curled up on my sofa in Los Angeles, I was reminded of that horrific day as I watched Andie MacDowell portray Paula, a mother with undiagnosed bipolar disorder, in the Netflix series, “Maid.”

A lot has been said about the platform’s most-watched limited series, with many focused on how the show sheds light on domestic violence through the experience of Alex (played by MacDowell’s real-life daughter, Margaret Qualley), but what I haven’t seen enough of is how the series highlights the struggle of having a parent with a mental illness.

In the U.S. where, according to a recent study, 7.2 percent of children have at least one parent or guardian who has poor mental health, it’s important that we continue to see examples on our screens of what mental illness looks like.

Watching Paula create chaos in her daughter’s life was like watching my mother’s volatile, narcissistic and paranoid behaviors. Both Mom and Paula left a trail of damage they were oblivious to.

It’s a trail that is all too common for children of mentally ill parents, which are a high-risk population. A 2020 Swiss study showed these children have a 3 to 5 times increased risk of developing mental health problems that require treatment. Compared to their peers, they are twice as likely to be abused and more than twice as likely to be placed in foster care than other children, according to a 2011 study of data from the Department of Social Services and the Department of Mental Health.

I never went into foster care, but like so many children who grow up in homes with mentally ill parents, I continue to endure the reverberations of years of emotional and physical abuse. After years of being screamed at by my mother, I avoided conflict at all costs, giving in too easily in my personal and professional relationships. I agonized over major and minor decisions, knowing my mother never let me forget a mistake. While raising my three children, I overreacted to normal childhood behavior and noises. After all, I tried to be the perfect daughter, dutiful and quiet, because I feared triggering my mother.

Like Paula, my mother’s mental illness caused her to shout hateful and damaging words. She blamed me for almost everything that went wrong in her life — from arguments with my father to her mother’s (who I called Mee Ma) debilitating stroke. I didn’t know any better. Guilt and shame engulfed me. I believed I caused Mee Ma’s stroke and eventual death because when I was 17, I pushed open her bedroom door to clean her room and my 90-pound grandmother fell to the floor. She was shaken but seemed OK. A few months later, she had a stroke.

Many moments with Mom were extreme and filled with outbursts, but there were also everyday signs of how her mental illness routinely played out in the background of our lives. Since she spent most of her days lying in bed reading, writing, napping or incessantly calling others about some imagined slight or drama, my brother and I ate a steady diet of Banquet chicken pot pies and Campbell’s soup.

I continue to endure the reverberations of years of emotional and physical abuse.

Different scenes in the series took me back to those everyday scenarios. Like when Alex picks up her young daughter, Maddy, from Paula’s care, she repeatedly asks if Maddy was fed. Alex had desperately needed someone to watch her daughter so she could keep her job. Her mentally ill mother was her last resort for child care.

According to the National Institutes of Health, nearly 20 percent of adults in the U.S. live with a mental illness (in 2019 that meant 51.5 million people).

When children couldn’t go to school because of the Covid-19 lockdown, I thought of the ones living at home with unstable parents, the way I did. I thought of the little triggers that might have set off episodes similar to my devastating haircut.

When Mom hacked away at my hair that day, she screamed that she couldn’t stand seeing it everywhere when she cleaned. This was ironic since my brother and I were the maids at home. Starting at a young age, we vacuumed, scoured and scrubbed.

After Dad, who also suffered bouts of depression, returned from work and saw my shorn tresses, he shook his head. He couldn’t rein Mom in when she was in a frenzy, though he did tell her to take me to a local beauty school that weekend to have the cut at least shaped. Dad believed in the Chinese cultural concept of favoring sons over daughters, so he gave whatever emotional labor he could manage to my brother.

In my traditional Chinese American family, we put on a good show and never spoke about mental illness openly. It was considered shameful, and my mother didn’t get adequate treatment because of that belief.

Long-term repercussions of having a parent with mental illness may include feelings of abandonment, difficulty trusting others, grief, low self-esteem and depression. I have struggled with these all my life.

In my traditional Chinese American family, we put on a good show and never spoke about mental illness openly.

For me, the most heart-wrenching “Maid” scenes depict Alex’s unfailing love for Maddy. I cried while watching them. Without the benefit of years of therapy, Alex was determined to minimize the damage of generational trauma.

It took years and hard work to claw out of the sinkhole that results from being the child of a mentally ill parent. The scars are still there, though time, maturity and therapy have helped cover the open wounds.

As a child and far too long as an adult, I tried to make my mother happy, to make her better ... until I realized I couldn’t. In order to save my own family, to save myself, I had to stop trying to save Mom. I limited my in-person interactions with her to fewer than six times a year.

I see the benefits of that decision in my own family.

My three children are now in college and graduate school. In between their visits home to see my husband and me, we meet on Sunday night family Zooms. My two daughters and I have dubbed ourselves “the Liu ladies” and enjoy sharing funny memes and interesting articles. They have even asked for my input on potential suitors on dating apps. These close relationships with my children mean everything to me because I never had them with my parents. I’m committed to giving my children what my parents couldn’t give me: steadfast love and emotional support.

April will be the 10th anniversary of Mom’s death. Looking back, I feel more empathy for her. As I often say, “mental illness is not a choice.” And yes, I loved her.