Overnight, the number of Americans using ranked-choice voting to elect officials roughly doubled. That’s because voters in New York City (population 8.6 million) overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure on Tuesday adopting the new voting system for some elections in the Big Apple.

In cities where ranked-choice voting has been adopted, candidates devote less time to attacking each other, and voters say they are happier with more civil and more positive campaigning.

New York now joins more than 15 U.S. cities and one state (Maine) in using the voting method, which is a significant improvement over the traditional process of whichever-candidate-gets-the-most-votes-wins. This reform is increasingly taking hold because the case for ranked-choice voting is simple and profound: It gives voters more options, allows them to express their preferences better, and makes politics more civil and cooperative.

Is it so profound that it can fix American democracy? Maybe. If you believe the biggest problem in American democracy is partisan polarization (as I do), ranked-choice voting is proven to counteract some of the “I win by making you lose” zero-sum logic of our current election style, incentivizing compromise, civility and moderation, and leading to more diverse candidates.

Especially when paired with multimember districts (larger congressional districts that have more than one representative instead of our current one-district, one-representative setup), ranked-choice voting could have a transformative power in reshaping our party system into something more sustainable and less destructive.

Under traditional “simple plurality” rules, candidates often win without getting a true majority, especially in a crowded field — a problem since it can allow organized minorities to rule over disorganized majorities. This often happens when independent and third-party candidates take votes away from major-party candidates, playing the role of spoiler. But under ranked-choice voting, there are no spoilers. Voters can select their favorite candidate without having to make the internal calculation of whether that’s going to help their least favorite candidate get elected.

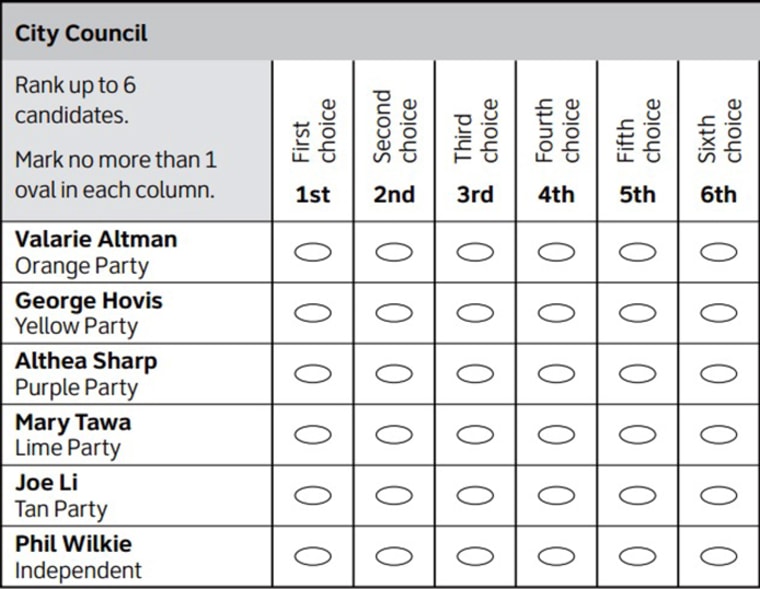

That’s because after selecting their favorite candidate, voters go on to rank the rest of the candidates in order of preference. If one candidate gets a majority of the first-place votes, he or she wins, as in the traditional system. But if not, as is often the case when there are more than two competitors, the candidate who comes in last is eliminated. Those who voted for that person then have their votes counted for their second-choice candidate. This retallying continues until there’s an outright majority for one competitor.

This encourages more candidates to run, expanding the field of voices, because minor party candidates are no longer dismissed as spoilers. It also changes the incentives of campaigning. In a whoever-gets-the-most-votes-wins election, it makes strategic sense to appeal to a limited but passionate base, so they turn out in large numbers, and go negative against your strongest opponents, so others shun them. But in a ranked-choice voting election, the strategic calculus changes. Since second and third (and sometimes even fourth and fifth) preferences matter, candidates have an incentive to appeal to one another’s supporters, and to build bridges instead of trying to tear one another down.

Thus, in cities where ranked-choice voting has been adopted, candidates devote less time to attacking each other, and voters say they are happier with more civil and more positive campaigning. This voting process also changes who runs and wins. Female and minority candidates, and especially female-minority candidates, tend to run and win more. Female candidates in particular tend to benefit from the less-negative style of campaigning that emerges under the new voting method because they tend toward a more cooperative style of campaigning.

While ranked-choice voting feels like a hot new reform, it actually has a long history in the United States — including in New York City, as part of the progressives’ broader municipal reform movement. In the first half of the 20th century, 24 U.S. cities adopted a multiwinner form of ranked-choice voting. New York adopted it in 1936, only to repeal it in 1947 when leadership of both parties saw it as a threat. Today, as then, it gives voters more choices, and has the potential to break the two-party dominance of American democracy.

It also has a long history around the world. Australia has used forms of ranked-choice voting for over 100 years. Ireland has used it for almost as long. Several other countries have adopted it more recently, including Fiji in 1999 and Papua New Guinea in 2007.

The more recent U.S. good government reform movement of the vote started when San Francisco approved ranked-choice voting in 2002 and replaced a costly two-round system with just one round, which also avoided the problem of serious turnout decline in run-off elections. It then got a big boost in 2018 when Maine voters approved the voting method. The state Legislature in Utah recently allowed all cities to use ranked-choice voting, and two piloted it this week. Next year will most likely see statewide ballot initiatives to use it in Alaska and Massachusetts.

Still, ranked-choice voting faces pushback from critics. Some argue it confuses voters, because it asks them to evaluate and research more candidates than they’re used to, and calculating the ultimate winner seems more opaque. However, we rank things all the time. What are you favorite flavors of ice cream? What movies do you want to see most right now? Thinking of ranked-choice voting as creating a political listicle can make it seem less intimidating.

Others argue that it allows reformers to manipulate election outcomes to obtain power. But all electoral rules favor some types of candidates over others. If ranked-choice voting is accused of privileging more moderate, compromise-oriented candidates over hard-line extremists, then it is guilty as charged. The fact that the first-round leader does not always win can also seem frustrating to them and their supporters, but the rules are clear from the outset.

Though critics assert that this change to the way we vote harms poorer, immigrant and minority voters, research shows that candidates of color have been elected in greater numbers once the change has been implemented. Other research shows that nonwhite and white voters both understand ranked-choice voting equally well, though older voters are more likely to find it a little confusing. In Minneapolis, which uses ranked-choice voting, 92 percent of 2017 voters described the process as “simple,” and by 66-to-16 said they wanted it to continue.And it seems to generate turnout on par with traditional elections.

Female and minority candidates, and especially female-minority candidates, tend to run and win more.

Certainly, it can sometimes take longer to get final results if there are many competitors and many transfers of votes as opponents are eliminated, and the process is not as straightforward as a simple winner-take-all tally. But contrary to scaremongering, that has not fueled conspiracy theories in the cities and countries that use it. In Ireland, vote tallying and transferring has even become an extended experience of civic involvement as the country watches the count.

To be sure, additional research is needed as more cities and states change their electoral rules. But from what we know so far, the benefits of ranked-choice voting far outweigh the costs. And they provide something our current political system has a short supply of: hope for a better future.