Washington, a town loaded with lawyers, is talking about how President Donald Trump can’t seem to find even one.

The Russia probe has put Trump in desperate need of a first-rate attorney. But one key reason he is unable to hire good counsel, Washington legal analysts say, is that he’s a terrible client. In lawyer lingo, this usually means that a client won’t do what his attorneys advise. (Here, Trump’s critics also mean that Trump doesn’t pay his bills, but that’s another story.)

Certainly, that’s what John Dowd, Trump’s former lead attorney on the Muller investigation, meant. After Dowd resigned, The Washington Post reported that he had been complaining about how Trump ignored his advice.

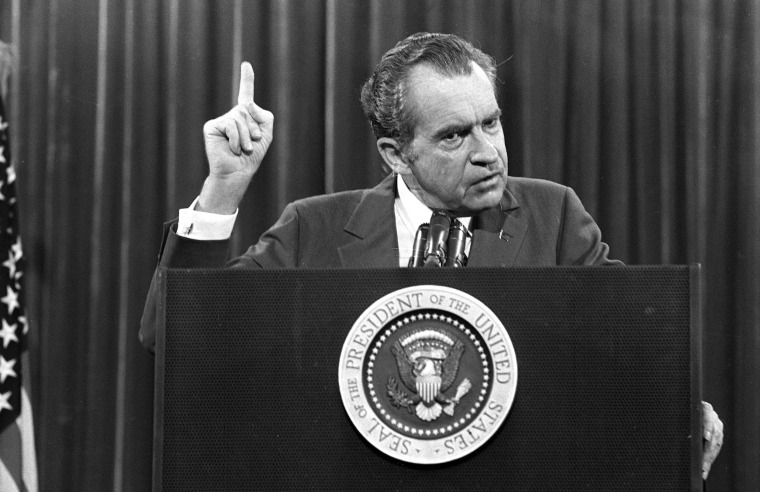

This problem is not new. During Watergate, President Richard M. Nixon wouldn’t listen to his lawyers either — as my late husband, Leonard Garment, found out while he was working in the White House as Nixon’s legal counsel at the time of Watergate. True, Nixon was himself a skillful lawyer, so he was ignoring his lawyers’ legal advice on a far more sophisticated level. But what played out during the Watergate scandal may help us predict what could happen now.

During Watergate, Nixon wouldn’t listen to his lawyers either — as my late husband, Leonard Garment, found out while he was working in the White House

To begin with, Nixon never really told his lawyers what was going on — violating a cardinal rule of the lawyer-client relationship. It meant that his lawyers couldn’t give him sound advice based on the facts of his situation. Garbage in, garbage out.

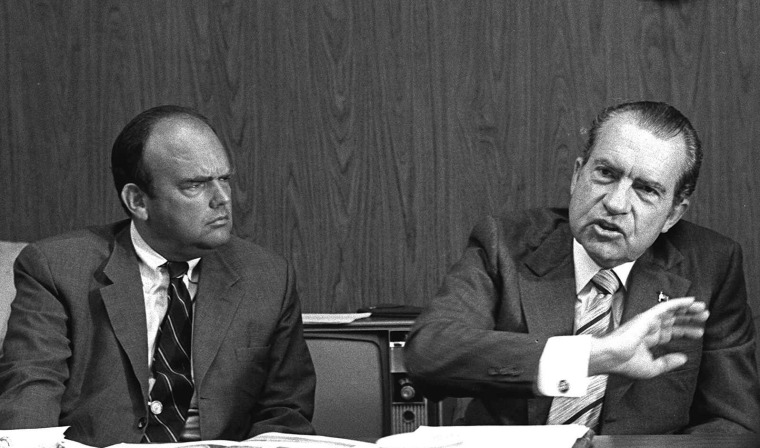

In fact, Nixon’s lawyers were often the last to know. They would hold earnest meetings, trying to piece together the facts of the case. Meanwhile Nixon would be conferring separately with political advisers like John Ehrlichman, then-Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman and White House Counsel John Dean in the Oval Office.

Among other missing details, Nixon never shared with his lawyers what turned out to be the fact most critical of his case: There was a taping system in the Oval Office.

Nixon made the situation even more abnormal by deciding to manage his own legal defense. In May of 1973, for example, the White House decided it had to issue a statement about Watergate that offered something more than the repeated boilerplate denials it had been providing. Nixon told his lawyers to draft the statement without any input from him. Then, the president said, they should send him their drafts, and he would revise them on the basis of his “recollections.” In other words, the lawyers didn’t have control of the product — the client did.

In 1973, Nixon appointed a new chief of staff, Alexander Haig, who often carried drafts of the statement between the lawyers and the president. Haig knew there was a taping system — but the lawyers didn’t. Some of Nixon’s “recollections” that he added to the legal statements were so detailed that my husband and the other lawyers thought there had to be a taping system. But they didn’t hear it from their client.

After Watergate, Nixon wrote that he was shocked when the tapes’ existence became public. He had expected White House staffers to invoke executive privilege when asked about them. Yet he had never even talked with his lawyers about whether an assertion of executive privilege would be justified, likely or successful. (It wasn’t; it wasn’t; and it wouldn’t have been.)

In fact, like Trump’s, Nixon’s legal defense team was quite small — fewer than a half-dozen attorneys. This may have been because hiring an outside lawyer to do personal legal work was viewed as an admission of guilt. But Nixon’s personal tics also kept the numbers small. He looked at the plausible candidates for the outside lawyer job and didn’t trust most of them — Joe Califano! Ed Williams! Experienced lawyers, yes, but Democrats! — with his political secrets. He would have trusted Bill Rogers, an old friend who was about to leave his job as secretary of state. But Rogers was too smart to bite.

The small size of the defense team was one factor that kept Nixon’s lawyers from being able to push back effectively against the hundreds of lawyers (literally) who had arrived in Washington to work for Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, for Sam Dash of the Senate Watergate Committee, for John Doar of the House Judiciary Committee — among others — to investigate and prosecute Watergate.

The final straw for Nixon’s legal team was also the starkest example of Nixon’s arrogance — and perhaps a warning for Trump.

Nixon remarked early in the Watergate scandal that he had John Dean “on tape.” When Archibald Cox heard about the remark, he asked what it meant. Nixon told his lawyers, who didn’t yet know about the taping system, that he was referring to a tape cassette (remember those?). So the lawyers wrote Cox a letter, saying just this.

In the fall of 1973, Judge John Sirica, who was in charge of Watergate prosecutions at the time, asked one of the Nixon lawyers where the cassette was. The lawyers asked Nixon about it. No problem, Nixon said: His lawyers could create a cassette from notes that Nixon had made.

Nixon, in other words, was asking — or telling — his lawyers to lie to the court. Within days, they began to make arrangements to leave the case quietly. Nixon’s defense continued to collapse until, nine months later in the summer of 1974, Nixon resigned rather than face impeachment.

Some of the troubles that Trump’s lawyers have had reflect the general problem of representing a president. But they also reflect personality.

Some of the collapse of Nixon’s Watergate defense reflects the difficulty of representing a president, any president. Presidents have political imperatives, president-sized egos and high-level secrets. In that sense, the legal representation of a president can barely be called a legal representation — it belongs to an oxymoronic category you might label “political litigation.”

But in other respects, Nixon sabotaged his own legal defense and made it almost impossible for his lawyers to do their jobs properly.

In the same way, some of the troubles that Trump’s lawyers have had reflect the general problem of representing a president. But they also reflect personality — and not just in the narrow sense that Trump is a “bad client.”

Even if Trump could become a “better client,” it’s unlikely he would be able to attract the superior lawyers who could save him from Special Counsel Robert Muller. They know that the Trump White House is simply not conducive to superior lawyering

“This is turmoil,” Theodore Olson, one of the lawyers who turned down the Trump defense, told NBC’s Andrea Mitchell. “It’s chaos, it’s confusion. It’s not good for anything.”

This is not the Nixon White House — but it could be another kind of graveyard for the reputations of even the best lawyers.

Suzanne Garment, a lawyer, is the author of “Scandal: The Culture of Mistrust in American Politics.”