Last week, the Annals of Internal Medicine published a set of guidelines by the Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians (ACP) addressing the problem of firearm-related injuries and death from a public health perspective.

The National Rifle Association (NRA) quickly rebuked the journal — and physicians in general — on Twitter, saying: “Someone should tell self-important anti-gun doctors to stay in their lane.”

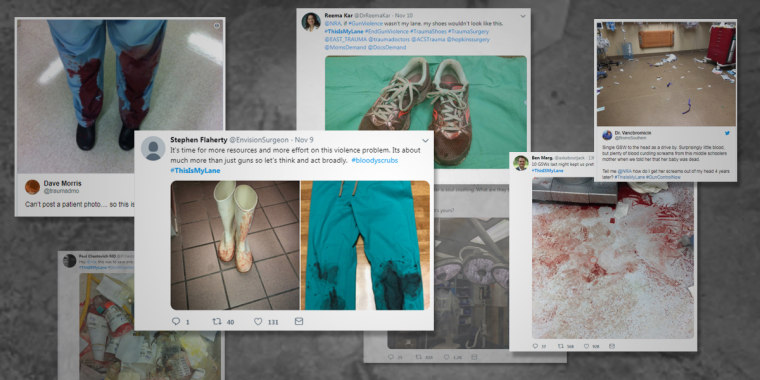

As a gun rights advocacy group, the NRA’s sharp critique was entirely expected. But the eruption from my physician colleagues on social media was startling. Responding to the NRA’s central point — that doctors should “stay in their lane” on the topic of guns — medical professionals created a viral hashtag, #ThisISMyLane (also #ThisISOurLane), sharing vivid stories of their clinical experiences with gunshot wound victims, arguing that, despite what the NRA might believe, the issue falls unavoidably into the laps of medical practitioners.

Physicians appeared on NBC and CNN, wrote editorial after editorial, and crafted an open letter to the NRA which read, in part: “physicians, nurses, therapists, medical professionals, and other concerned community members want to tell you that we are absolutely ‘in our lane’ when we propose solutions to prevent death and disability from gun violence.” As of this writing, the letter — which concludes with an invitation for the NRA to “collaborate with us to find workable, effective strategies to diminish the death toll” — has been signed by over 30,000 health professionals, an uncommon display of solidarity.

Why was the response so impassioned? Because the medical community has been censored on this issue before, and it was to our shame and regret.

Over the past 30 years, physicians — working in concert with epidemiologists, social workers, basic and clinical scientists as well as a wide variety of health workers, communities and industries — have helped achieve major public health victories, including reductions in cigarette smoking and motor vehicle accidents, as well as life-saving treatments for HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C.

But we have stood by helplessly on firearm safety as politicians and lobbyists blocked us from applying standard scientific approaches to gun violence. We weren’t admonished to stay in our lane, exactly — instead we were told to ignore a health crisis unfolding right in front of us, squarely in our lane. And for the most part, we did.

Health professionals have realized we can no more neglect searching for solutions to gun violence than we can decline to resuscitate a patient dying of sepsis or heart failure in front of us.

Ultimately, however, health professionals have realized we can no more neglect searching for solutions to gun violence than we can decline to resuscitate a patient dying of sepsis or heart failure in front of us — or to refuse to work toward preventing the next case. We don’t stand at bedsides categorizing health problems as “politically acceptable” or “too hot to handle.” We care about them all, and this is never truer than when harm is preventable, as with most injuries. The healthy toddler who fell out of an unsecured window, or into a pool with a gate left ajar. The suicide in which the most accessible means of self-harm was a particularly effective and irreversible one.

While doctors want to prevent harm as a general concept, the trauma of gun violence is accompanied by a specific experience. As signified in the #ThisIsOurLane hashtag, caring for trauma victims does not allow us to forget our responsibility to mitigate suffering. And now the country is witnessing what happens when the burden of this cumulative horror is borne by a new generation of physician-advocates increasingly uncomfortable with inaction.

Today, the notion that physicians should be restricted to bedside caregiving is hopelessly antiquated. Advocacy training is now a standard component of residency curricula. The roles of physician and public health advocate grow more intertwined with each passing year. Many of our healthcare leaders have been outspoken about the necessity of physicians to advance health through advocacy.

“It is chilling to see the great institutions of health care, hospitals, physician groups, scientific bodies assume that the seat of bystander is available. That seat is gone,” wrote Dr. Donald Berwick, the former director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, in a 2017 commentary in the Journal of the American Medical Association. “To try to avoid the political fray through silence is impossible, because silence is now political. Either engage, or assist the harm. There is no third choice.”

Sitting in silence while we treat gunshot wound after gunshot wound is no longer possible, unless we wish to be complicit in perpetuating the problem.

The rising generation of physicians is more wired to this message than any before, and it is their voices that moved me most this week. Sitting in silence while we treat gunshot wound after gunshot wound is no longer possible, unless we wish to be complicit in perpetuating the problem.

Is it difficult to fight the status quo? It is. But those who have been in a trauma room, soaked to the skin in the blood of a child who was healthy an hour ago, watching his eyes dilate to black and knowing all is lost — well, we have received a clear, strong directive.

Few physicians can tell you how a carburetor works. But we can tell you, with impressive accuracy, how every beer you consume affects the possibility that you will be in an accident if you drive afterwards. There is a tremendous amount of literature on this topic. And note: We don’t argue for universal abstinence from either drinking or driving. We can be both deeply interested in mitigating the established harms of alcohol, while still at peace with the six-packs of beer in the fridge and the cars in the driveway of homes across the country (including our own).

The same goes for firearms. Like swimming pools, hang-gliders and airway-sized chunks of hotdog, guns are not going away any time soon, and we hope to coexist with them while minimizing their potential to rip away the lives of our loved ones.

Doctors and other healthcare workers are not looking to be extreme in our approach to firearm injuries. We only wish to consider gun safety using the same bland, unexciting, methodical, scientific framework we apply to any other threat to the public’s health.

Stay in our lane? Doctors are comfortably in their lane, and that lane includes an imperative to reduce firearm injuries and deaths. It always has. We welcome all those invested in the health and wellbeing of Americans, including NRA members, to join us in our efforts.