After a monthslong trial, a jury on Thursday recommended Nikolas Cruz receive life in prison without parole after he pleaded guilty to killing 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in 2018. Though many were shocked he didn’t receive the death penalty, and many victims’ family members were visibly upset by the decision, it’s wrong to assume this would have automatically brought them solace.

The lengthy proceedings stirred up decades-old memories of waiting to find out whether my own mother’s murderer would receive the death penalty. While her killer was put to death, the sentencing and ultimate punishment he received in many ways made it more difficult to move forward in my life and achieve any sense of closure.

The pain of a drawn-out process is just one aspect of seeking the death penalty that doesn’t make capital punishment the salve for victims’ families that it’s often presented as, and I think it’s important that the public understands what they’re imposing on the victim’s family as well as the offender when they seek a death sentence.

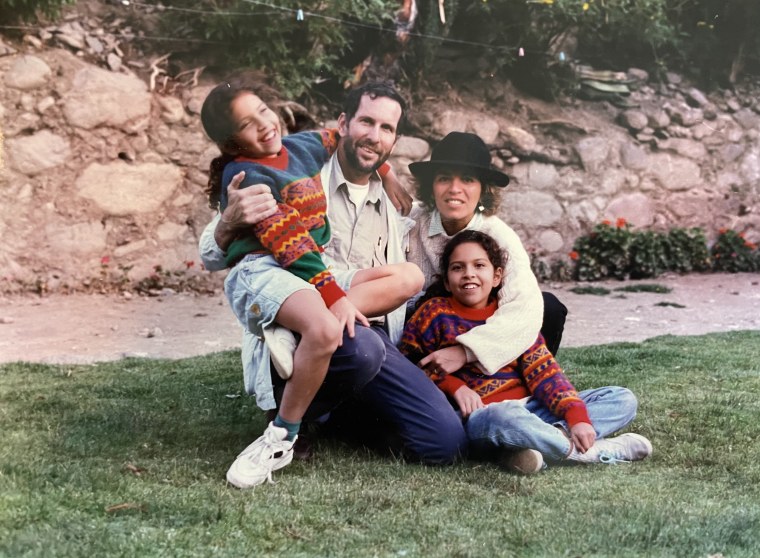

My mother, Claudia Benton, was murdered by Angel Maturino Resendiz, a Mexican immigrant in the U.S. illegally and known to many as the “Railroad Killer,” in 1998 when she was 39 and my twin sister and I were 11 years old. Before my mother was killed, I was aware of the concept of capital punishment (I lived in Texas, the most capital-punishment-happy state in the nation, after all), but at that age I unsurprisingly didn’t have a solid opinion formed.

As an adult, I can’t say I have a clear-cut stance on it, either. Yes, it’s our legal system’s duty to hold people responsible when they commit violent crimes, and it’s a slap in the face for victims’ families to not see that happen. My mother’s killer had been previously sentenced to more than 20 years in prison for assault and burglary but was released much earlier than that, leaving him free to kill her. It’s the prime example people use when they’re surprised to learn I’m not fervently in favor of the death penalty.

But as a person of color, it’s also hard for me to ignore the fact that the system is hardly equal, with the death penalty more likely to be invoked in cases involving Black defendants and white victims. My mother was actually a Peruvian immigrant, a fact much of the widespread media coverage surrounding her case conveniently omitted. I have often wondered if her case would have received the same level of attention or sparked the same widespread calls for justice if she hadn’t been a white-passing doctor who shared my white father’s last name and lived in one of the most affluent parts of Houston. Such disparities open the door to the risk of putting innocent prisoners to death.

Sometimes family members of victims do have clear-cut feelings that the death penalty is needed. My Republican-leaning father and his side of the family agreed that it would obviously be the only “right” ending to this whole ordeal.

But once Resendiz was finally captured, I couldn’t wait for the case to be over. Outsiders often don’t realize how much a death sentence actually draws out a murder case, further preventing the opportunity for survivors to feel any closure.

While my mother’s killer was sentenced to death in the summer of 2000, Resendiz wasn’t actually executed until six years later, when I was 19. As is the case with many similar verdicts, his execution was delayed by several appeals. In the process, his own lawyers cited mental health issues and the Mexican government challenged the decree as cruel and unusual punishment. (In the case of Cruz, jurors were presented with testimony that his mother drank heavily during her pregnancy and that he witnessed his father’s death when he was 5.)

These delays not only made the experience harder emotionally in terms of when I could start to search for closure, but also by having to continue to see people like Resendiz’s lawyers and the Mexican government try to humanize my mother’s murderer in their attempts to excuse his actions.

When the death sentence for Resendiz was handed down, those close to us expected my family to immediately feel vindicated. But I didn’t experience that at all. In fact, it only added to my emotional pain because his execution only made it all the more real that my mother was gone.

The verdict didn’t change the fact that my sister and I grew up without our mother. It didn’t allow her to live out her own professional aspirations as a physician and researcher, much less see us pursue ours. And it certainly didn’t help the media move on from their focus on her killer’s story, which continues today in true crime entertainment.

Want more articles like this? Follow THINK on Instagram to get updates on the week’s most important political analysis

Those deciding a convicted killer’s fate aren’t the ones who live with the impact and aftermath of the crime in question. It’s time for everyone in this country, from lawmakers to the general public, to prioritize the effect of the death penalty on a victim’s survivors over their own political ideologies.