Last month, pop singer Billie Eilish reignited the well-tread topic of truth in art by questioning the validity of certain rappers' lyrics in a cover story for Vogue's March issue. Eilish disputed the legitimacy of the lyrical claims made by some of her peers, especially in regard to toting guns and womanizing — basically violence and general lifestyle excess.

Eilish's comments did not go over well with a handful of critics, which is unsurprising since this is a long labored-over discussion. It's also not likely to end anytime soon.

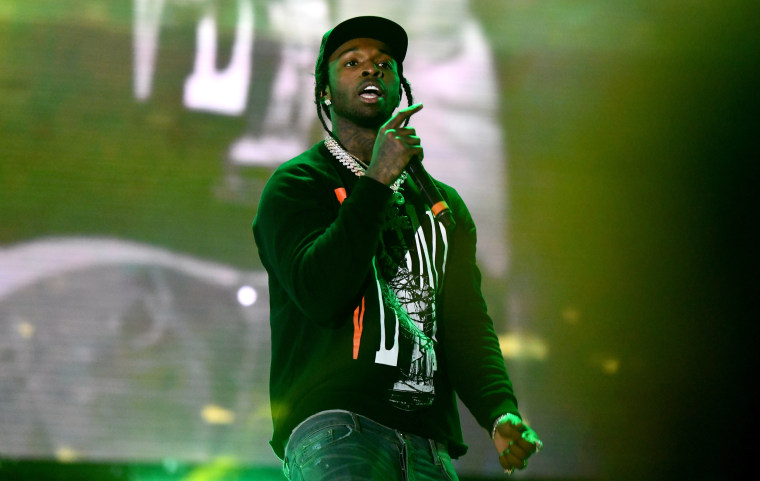

A number of recent tragedies suggest that the idea of authenticity can actually be pretty dangerous. The violent shooting death of the rising rapper Pop Smoke at the age of 20 has already yielded yet another grieving mural unveiling in Brooklyn as a tribute to a slain artist. The rapper was laid to rest on Thursday in Brooklyn after a procession attended by hundreds.

Rather than condemn Eilish, it is perhaps more helpful to talk about what truth means in the context of pop music — and who has to suffer for that truth.

Rather than condemn Eilish, it is perhaps more helpful to talk about what truth means in the context of pop music — and who has to suffer for that truth. This discussion starts with a paradox: If the artist is not actually living the life described in their music, they can be criticized as fabricators or worse. But if every line is even close to true — the drug trafficking, the suicidal threats, the boozing, the violence, the promiscuity — it will likely lead to a brief flicker of a career.

Because when it comes to the authenticity dispute, winning is hard to come by. Musicians are either faking it or are irresponsible shepherds leading society toward a hastened decline. Either way, there is evidence to support that artists have a shorter life expectancy than the rest of society, enough to render this infinite debate moot.

Twenty years into the next millennium and popular music has been plagued by untimely deaths, shooting incidents and overdoses. Amy Winehouse's drug and alcohol issues eerily harked back to the singers who inspired her, up until her death in 2011. Other more recent high-profile overdose deaths include Mac Miller, Lil Peep, and Juice WRLD — who died of a seizure after being confronted by police while carrying drugs.

As a 2016 study titled "Life Expectancy and Cause of Death in Popular Musicians: Is the Popular Musician Lifestyle the Road to Ruin?" noted: "Mortality impacts differed by music genre. In particular, excess suicides and liver-related disease were observed in country, metal and rock musicians; excess homicides were observed in 6 of the 14 genres, in particular hip hop and rap musicians. For accidental death, actual deaths significantly exceeded expected deaths for country, folk, jazz, metal, pop, punk and rock."

There is a veritable micro-industry of books reflecting on the often-dark lives of our favorite musicians. There are bible-size tomes with titles such as "Everyone Loves You When You're Dead: Journeys Into Fame and Madness,"; "The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars: Heroin, Handguns and Ham Sandwiches"; and "Better To Burn Out: The Cult of Death in Rock 'n' Roll." "The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars" — at 600+ pages — even has a handy calendar to keep up with the daily notable obituaries of fallen rap, rock, reggae and country musicians.

That's not to mention the glut of hastily fashioned documentaries that marked the late 1990s and early 2000s — “E! True Hollywood Story” and VH1's “Behind the Music” series brought an often sensational perspective to the descent and rapid decline of a number of artists and bands.

Jazz and blues biographies are filled with guns and drugs and violence and tragedy, from singer Billie Holiday's struggles with heroin use and harassment from vice cops to blues pioneer Memphis Minnie's rumored familiarity with weapons. Often these glamorized dalliances with lawlessness and self-medicating have more to do with the race and class issues of the era; Holiday said she would think of her father's death after he was barred from medical care at a Jim Crow-era hospital when singing the early protest song, "Strange Fruit."

While a string of rock star drug deaths in the 1960s and '70s added to the evolution of this discussion, the self-congratulatory mythology of those decades often rings hollow. But starting in the 1980s, the late 20th-century martyrdom of John Lennon marks a definitive break from the Rock Era — a man who preached peace in his lyrics but struggled with his own abusive tendencies was gunned down, assassination-style. The unsolved homicide of punk figure Nancy Spungen, the death by suicide of Joy Division singer Ian Curtis and the overdose of Germs' singer Darby Crash had a direct impact on three specific styles of music that would go on to shape the last two decades of the millennium. And all the while, hip-hop was beginning its rise.

While a string of rock star drug deaths in the 1960s and '70s added to the evolution of this discussion, the self-congratulatory mythology of those decades often rings hollow.

From the beginning, hip-hop's designation as a serious new form of music stirred controversy. As other genre purists protested, it was defended as a stand-in for mainstream news for the communities it served and as a vital cultural force that would reclaim much of the mainstream influence on fashion, radio, television and movies that had been lost to predominantly white rock music. But as hip-hop evolved, even some of its supporters weren't ready for it to take on increasingly grim subject matter.

Author and journalist Ronin Ro wrote a decidedly anti-rap book in 1995 titled "Gangsta: Merchandising the Rhymes of Violence" that took exacting aim at lyrical substance, particularly in the case of Houston rapper Scarface: "It was amusing: Scarface and his ilk sensed that the public was tired of the recurring motifs in gangsta rap and yet they would not, or could not change. ... Under the pretense of 'street reporting' they negated anything positive they may have had to offer."

While Ro is a devoted hip-hop fan, he spends nearly 200 pages sounding very much like the chiding politicians who railed against the music of the day. Criticism of content in rap and hip-hop music eventually reached the highest office in the land, with multiple presidents speaking out against artists — George H.W. Bush on Body Count and Ice-T, and Bill Clinton on Sista Souljah. Rap was the new scapegoat for all things wrong with America. (It should be noted that Ice-T’s band Body Count is actually a thrash metal band.)

Ice-T squaring off with the executive branch over lyrics now seems laughably quaint. And a spate of deaths in the mid-to-late 1990s pushed rock and rap fans more closely together. As Dax-Devlon Ross notes in "The Nightmare and the Dream: Nas, Jay-Z and the History of Conflict in African-American Culture," there was a shared interest for more adult subject matter across genres, or as he puts it: "MTV was beginning to notice the link between the rebellion reverberating from grunge bands like Nirvana and Pearl Jam and the outlaw aesthetic of mega-popular rappers like Snoop Dogg and Cypress Hill."

Ross spends much of his book exploring the lyrical feud between Nas and Jay-Z, who commented on each other’s legitimacy often. Diss tracks and artist disagreement is itself not new. Van Halen's David Lee Roth famously accused The Clash of drinking iced tea out of a Jack Daniels bottle in an enduringly goofy clip from the 1980s. Latinx rappers like Kid Frost accused NWA of lifting Chicano gang culture's aesthetic and lowrider car imagery.

There are even disagreements within groups. Black Flag vocalist Henry Rollins’ life-on-the-road epic "Get in the Van" memorialized the punk band’s brawl-plagued journey as it blazed yet unexplored trails across the international underground. But the band's founding guitarist, Greg Ginn — Rollins' own bandmate — has maintained that much of the rugged content is exaggerated.

All of which brings us back to the passing of Pop Smoke. Not many details are public, but police have confirmed that he was the victim of a home invasion after inadvertently posting his address on social media. A lone paragraph from the L.A. Times report on the artist's cause of death stands out: "Investigators suspect the home where the rapper was staying was targeted by the assailants. In recent years, Los Angeles residences being rented by musicians have been the target of several home invasions, according to law enforcement sources."

Pop Smoke's music is part of the Drill movement. Another young Drill pioneer — Chicago's Lil Mouse — was shot in 2017 but survived; He was 18 at the time. Kevin Fret, an openly gay Puerto Rican trap musician who challenged the idea of what a rapper could wear onstage and look like, was shot on his motorcycle in 2019. His death has yet to be solved. All of the above artists did not shy from self-expression on the dangers of contemporary life, from Lil Mouse's early single "Get Smoked" to Fret's unforgettable pink assault rifle.

The public expects artists to be arbiters of the truth. While Eilish raises interesting points on image versus reality that are important to fans, there should also be an awareness of the cost of true authenticity. Much of that cost feels as if it has already been paid. The world is often better off when it turns out the artist is lying.