By the time the likes of Mötley Crüe, Poison and Guns N’ Roses had taken over Los Angeles’ Sunset Strip and, soon after, the then-all powerful MTV in the late 1980s, it seemed that the area’s once burgeoning punk scene had truly breathed its last. The Go-Go’s, once darlings of the genre, had topped the charts and then split, Henry Rollins had left the already legendary Black Flag for a mercurial solo career, and the granddaddy of L.A. punk, the band X, had splintered before a film of its remarkable rise, Unheard Music, had even premiered.

“It felt like shit,” X’s John Doe says today. “It felt like we got passed over. It felt like someone didn’t invite us to the party. You just keep doing what you’re doing, but once the stoplight has moved away from you, you feel like, ‘Wait a minute, I didn’t do anything wrong. I just got older, or things changed.’ It was a little bitter.”

It’s a remarkable read, making a compelling case that the do-it-yourself and truth-to-power ethos punk espoused is as alive and well in 2019 as it ever has been.

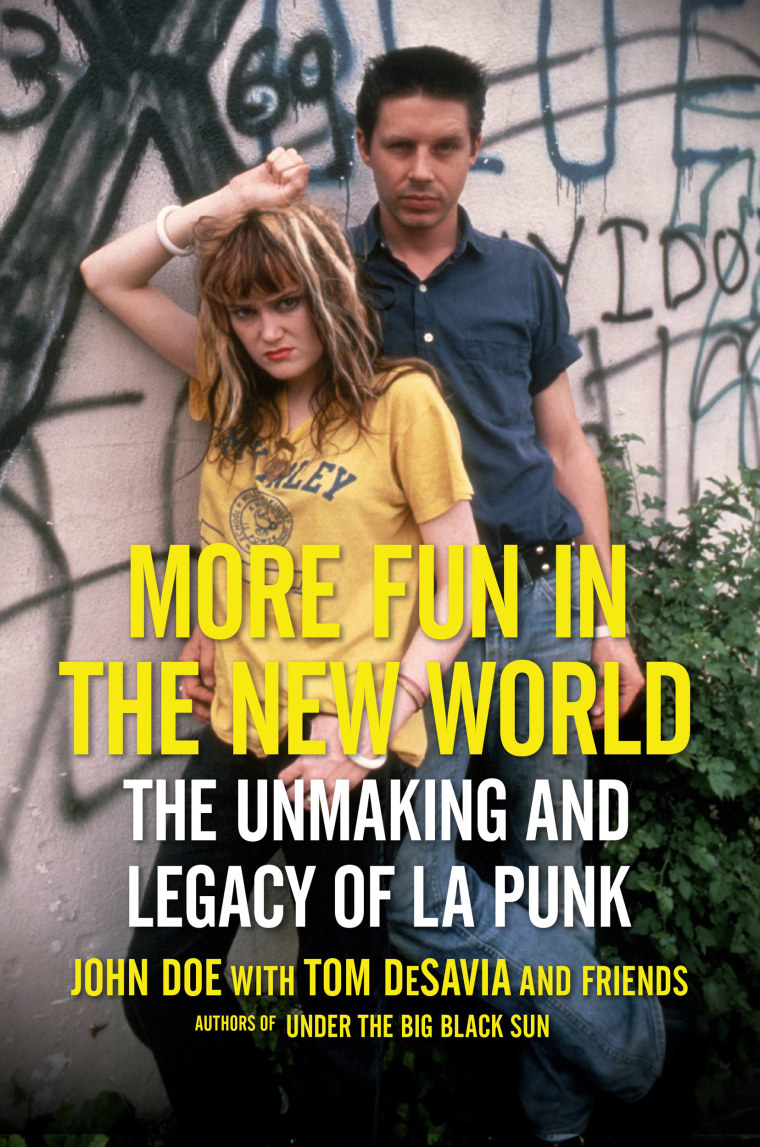

But did punk actually die? A new book written by Doe, Tom DeSavia and a who’s who from L.A. punk’s heyday, documents the rise and fall (and rise, again) of Los Angeles punk rock. It’s a remarkable read, and rewrites the latter history of punk — and most especially its LA-based version — making a compelling case that the do-it-yourself and truth-to-power ethos it espoused is as alive and well in 2019 as it ever has been.

“The metal bands, I’m not sure they were singing anything that was life-changing or inspirational, or even super thoughtful,” the Go-Gos’ Jane Wiedlin recalls. “Whereas I think part of the punk ethic, especially with bands like X, they really had something to say. Something deep. Something profound. Something beautifully stated. And that’s why I will always be proud to be in the punk side, because we brought an art form to music, which is already an art form. We doubled down.”

“More Fun In The New World: The Unmaking and Legacy of L.A. Punk,” picks up where Doe and DeSavia’s first volume, released in 2016, left off. It tells the tale of the riotous times and thrilling exploits of some of L.A. punks most notorious names, as well as the long, slow demise the scene faced as rampant drug abuse took hold, and the 1980s, and the Reagan era L.A. punk so neatly chronicled, wound down.

“The first act was over, and the second act was to be determined,” Doe says of the period where the new book picks up. “It wasn’t so much that the hair bands won, or that hardcore took over, but that the community and Camelot had dissolved.”

“When you have a smaller scene and bands break out of that scene and become famous, there’s a lot of resentment and hostility,” Jane Wiedlin adds. “There’s always that whole idea of being a sellout, but in the punk scene, it was super hardcore, the idea of being a sellout. There was very little that was worse than that.”

But while “More Fun In The New World” is a rollicking tale of punk’s hedonistic heyday and ultimate disintegration, it’s also a thoroughly engrossing redemption story.

“When you’re a kid, you don’t think in terms of legacy and what’s going to be around forever,” Doe’s co-author Tom DeSavia says. “Five years seemed like 20 years back then, because everything about punk seemed so urgent at the time. It was all-consuming.”

Once punk went into its downward spiral, some in the music industry wrote it off for dead. But people such as skateboarder Tony Hawk and artist Shepard Fairy weren’t ready to let it die.

Once punk went into its downward spiral, some in the music industry wrote it off for dead. But in fact, people such as skateboarder Tony Hawk and artist Shepard Fairey, not to mention the kids who had grown up in the punk scene, weren’t ready to let it die. Indeed, the punk aesthetic remains prevalent today in pop culture.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but that sense of community, and how we were this secret society that no one knew about, was so exciting,” Wiedlin recalls. “I had been raised to be a good girl, to keep my mouth shut, to always be pleasant. When I discovered punk, I also discovered there was another way to be: To be bold, to be yourself, to have opinions.”

Want more articles like this? Sign up for the THINK newsletter to get updates on the week's most important cultural analysis

For Doe, despite the rampant drug use he recalls as “rampant and destructive,” late-era L.A. punk was far from a spent force. There was a power there, a creative force that maybe blurred the lines between punk and rock a little, but still stayed true to the attitude of punk itself.

And while the London and New York punk scenes often take precedence in terms of media attention, as well as market nostalgia, “More Fun In The New World” makes a compelling case that L.A.’s remarkably diverse group of bands left behind a special legacy that’s still thriving and inspiring new generations of artists.

“You can take that punk rock attitude and, if you apply it to film, you get Allison Anders,” Doe explains. “If you apply it to acting, you get Tim Robbins and the Actors’ Gang, if you apply it to art, you get Shepard Fairey and if you apply it to skateboarding, you get Tony Hawk.”

Most of all, however, Doe seems grateful for the second look many first-generation punk fans are giving the work he and his contemporaries created, as well as the fresh eyes so many younger people are giving it.

“When I see a 15-year-old looking at (X frontwoman) Exene, thinking, ‘She’s cool,’ as a role model, that makes me really happy,” Doe says. “It makes me very gratified.”

Ultimately, Doe hopes that people who read his book are inspired by the characters in it. “You discover something whenever you’re ready for it, and then your world is changed. That’s what we hope we’ve done by continuing the story with this book,” he says. “You hope that it turns people on to something that they didn’t know, because then you’ve got another person whose mind is a little bigger, a little more open. The first book was sex and drugs and rock and roll and destruction and alienation and the country going to hell. So finding the legacy part of it, in writing this book, was a bit of redemption.”

“I don’t feel people are going to be throwing punk rock music out with the bathwater anytime soon,” Wiedlin adds with a laugh as we wrap up our interview. “What surprises me, though, is that my boyfriend has two sons in their 20s, and they listen to real punk music, California punk music from the 70s and the early 80s. I find that so exciting, but shocking at the same time.”

Shocking indeed. While London’s art school-fueled scene and New York’s nihilistic preening may have been short-lived, as Doe and his punk co-authors have laid out so persuasively in two best-selling books, the spirit of L.A. punk is alive and well, with no end to it in sight.