My 3-year-old can't say his R's, so every time I finish reading "A Big Guy Took My Ball" by Mo Willems to him, what he actually says is, "Weed it again."

Recently, I pointed out that, not only had I just read him this book, but I had also heard his mother reading it to him earlier. Unmoved by this reasoning, he countered: "Weed it. Again."

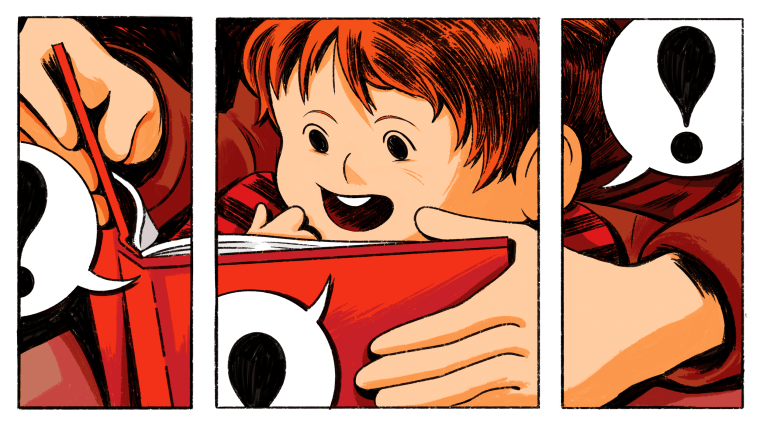

So I wed it again, and I've wed it again since then, too. Sometime around the 50th weeding — possibly the 55th — either Stockholm syndrome began to set in or I finally noticed the true nature of the book: "A Big Guy Took My Ball" is a brilliant graphic novel.

Then I picked up some of my son's other Elephant and Piggie books and discovered that they, too, are brilliant graphic novels. And I'm not kidding.

Generally speaking, kids' picture books get little love from great thinkers; they certainly get far less than prose books for kids — which are the subject of enormous and energetic (and sometimes toxic) debate — or the young adult genre. And they definitely get less thought than comics written for adults.

But then, most of us no longer think of comics as being (and remaining) hugely popular with kids. Dav Pilkey's "Dog Man" comics sell in the hundreds of thousands of copies every month — far more than any contemporary superhero comics — and they're also the only comic books I've ever seen a real-life kid carry around on the playground in nearly four years of parenthood.

It's all the sort of thing that literary cartoonists are justly praised for doing, but drawn in a way that can be understood by somebody whose consciousness is still developing.

Often, it seems that so many books and articles have been written about grown-up comics (usually with titles like "Pow! Zap! Comics Aren't Just for Kids Anymore!") that the kids' stuff — whether comic or picture books — is indicted, by implication, as silly non-art, not worthy of deep thought.

But children's picture books use the same storytelling tools as "The Hard Tomorrow," "From Hell" or "The Sandman" to teach our kids how to think.

Let's take my favorite Elephant and Piggie book, "Waiting Is Not Easy" — a sort of Samuel Beckett play by way of Fisher-Price: The background gets slightly darker every few pages until nightfall arrives and the pages are overwhelmed by a photograph of the star-filled sky. When he's upset about having to wait, Gerald the Elephant's groans fill the page, bowling Piggie over with his frustration, which is a perfect demonstration of the enormity of his feelings.

It's all the sort of thing that literary cartoonists like Chris Ware are justly praised for doing: using comics to map out early consciousness, as Ware does in his wonderful book "Rusty Brown," but drawn in a way that can be understood by somebody whose consciousness is still developing.

Kids' brains, after all, work through repetition. The Elephant and Piggie series has been read a bajillion times in our house not because of the brilliant lettering (which is brilliant) but because, in "Let's Go for a Drive," the characters dance and shout "DRIVE! DRIVE! DRIVEY-DRIVE-DRIVE!" every four pages, and my kid also dances and shouts "DWIVE! DWIVE! DWIVEY-DWIVE-DWIVE!" when they do. (Plus, he loves to find the pigeon from another Willems series playing with Gerald and Piggie on the books' endpapers — the most ambitious crossover event in history, in his opinion.)

And because of Gerald and Piggie, I have started to see graphic novels everywhere as I read to him. Maurice Sendak's "In the Night Kitchen" is a good time for little children, but it's also obviously a riff on Winsor McCay's "Little Nemo in Slumberland" cartoons — right down to the way the hero falls into bed at the end of the story. Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the Holocaust biography "Maus," quietly turned his groundbreaking grownup comics anthology "RAW" into the kid-tastic "Little Lit." Many of the contributors are the same people; they're just drawing fairy tales for children now.

And these are texts vital to the most important reader of all: my son.

Great comics creators know about this intersection. A few years ago, Neil Gaiman, author of "The Sandman," wrote a "last" Batman story with artist Andy Kubert called "Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?" As the Dark Knight dies, his brain shuts down and he tells his world goodbye in a moving homage to Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd's "Goodnight, Moon." (Gaiman also writes kids' books, including several that are illustrated with comicky word balloons. "Crazy Hair," by Gaiman and Dave McKean, is the one I have been recently sentenced to read over and over again.) "From Hell" writer Alan Moore has dropped picture-book interludes into several of his adventure comics. "The Hard Tomorrow" author Eleanor Davis adapted the nursery rhyme "The Queen of Hearts" into a swashbuckling anticapitalist comic strip for a kids' comics anthology.

The different-colored word balloons that make it clear which character is speaking and the simple syntax and cadence make eventually reading a book himself a less intimidating prospect.

Perhaps it's ridiculous to be shocked by this; after all, narrative picture books are narrative picture books. But my kid and I are very different audiences: I love the giant two-page spread in the middle of Willems' "The Pigeon Needs a Bath," in which The Pigeon runs through a classic list of reasons not to get into the bath, whereas my kid loves the spread three pages later of The Pigeon playing in the tub, because it has a picture of The Pigeon covered head to toe in bubbles, with only his eye visible. That's just way too many bubbles, and my son makes me stop reading and announces, through gales of laughter, "You can just see his eye!" (He does this every time we read the book, and he wants to read the book every day.)

Willems' books — and Pilkey's, which my 3-year-old also loves — are obviously speaking a language I recognize: the language of all comics. But they're also talking to a much younger, more malleable person's changing brain, and in terms he understands instantly. Plus, the different-colored word balloons that make it clear which character is speaking and the simple syntax and cadence make eventually reading a book himself a less intimidating prospect.

As the pandemic has worn on, I've been increasingly worried about my son's access to educational resources at a crucial moment, but Willems' books seem to be taking at least part of the load off my mind. At 3, my son has a few works he recognizes on sight, and he can tell me what some short combinations of letters spell. He can recite most of the Elephant and Piggie books from memory, of course; sometimes he assigns the part of the Gerald the Elephant to me and does all of Piggie's lines himself, like a little play. But if I point to a word on the page and ask him what it means, he knows it far more often than I expect him to.

I'm grateful to Willems for that, and to the language of words and pictures for helping fill in the gaps I didn't expect would have been here this year. And, thanks to a graphic novel with an elephant, a pig and some very simple syntax, I'm a little more hopeful for my kid's future.