Migration is central to the human experience. For as long as we’ve been around, people have been moving from one place to another. Though it’s never been easier to get from point A to point B, the inequality between those places could be as great as they’ve ever been. We’re now on the front edge of a climate crisis, launching the greatest period of human migration that will ever have happened on the planet. The backdrop of this great migration, however, is a political landscape marred by virulent reactionary movements against immigrants.

So how do you reconcile this vitriol with the impending climate refugee crisis? Suketu Mehta immigrated to this country as a teenager. Now, he’s written a manifesto about his vision of America and what it means for the country to be welcoming to the stranger. It’s a book he says he felt compelled to write after seeing how Donald Trump stands as a threat to that vision.

SUKETU MEHTA: I can completely understand why Iowans might like to keep Iowa what it is. But then they also have to realize that these people who want to come to Iowa from El Salvador and from Guatemala, they're coming there because we have left them no choice. They are coming to Iowa, and to Illinois, and to New York because Americans have gone into these countries and ruined their countries for decades now.

CHRIS HAYES: Hello and welcome to "Why Is This Happening?" with me, your host, Chris Hayes.

Well, as long as humans have been on the planet, they've been doing a few things consistently. I mean, there's things they do at different periods in history, but there's a few things they have always done: eat, have sex, do some kind of worship of a god, and migrate, move around.

I mean, we know from the fossil record and that humans started in one very specific place in this world, and after enough time they got everywhere. The way they got everywhere was moving around, migrating.

In fact, for a long period of time, I think about 200,000 years before we get what we call civilization and we settled down, moving around is what humans do to survive. We are hunters and gatherers, and what hunters and gatherers do by definition is not stay in one place. They move around foraging for food, following animals that they can hunt and kill to eat.

And so, movement — humans moving from place to place — is as deeply embedded in us as a species, as almost anything that we do. It's wild to consider the fact that this continues on into early human history throughout civilization. I mean, human travel or going from one place to another, even way back during periods of time in which it was inordinately difficult to do so, is still a central human experience.

You go back and you look at the Bible, and you look at Sodom and Gomorrah. What is the sin of Sodom and Gomorrah? Ultimately, the reason that God brings his wrath down on Sodom and Gomorrah is because He sends in a few angels as strangers, as immigrants into the town, and they beat up and assault those immigrants. That's the test of virtue for this town. God's test for virtue — sending in strangers.

Read the writings of the Roman era, and it is just wild to imagine how much movement and migration and mixing of cultures there are 2,000 years ago. There's no airplanes, there's no fossil fuels, it's not easy to get from place to place, but people move around. Jesus is born in Bethlehem because people move around.

It is one of the fundamental constants of human life on the planet. And I say that because right now, that fundamental constant is supercharged by a bunch of things that are happening in our world. The lingering effects of colonialism, the distance between the developed world and the developing world in terms of access to things like health care, jobs, money and affluence, combined with the ease of travel. We can now fly around, we can take vehicles that have fossil fuels. It is easier to get from point A to point B than it has ever been in human history. And the inequalities between humans are probably as great as they've ever been in history.

So you combine those together and put atop of that, the fact that we are on the front edge of a climate crisis, which is going to chase hundreds of millions of people from the places they live, we are in the midst of and entering the greatest period of human migration that will ever have happened on the planet.

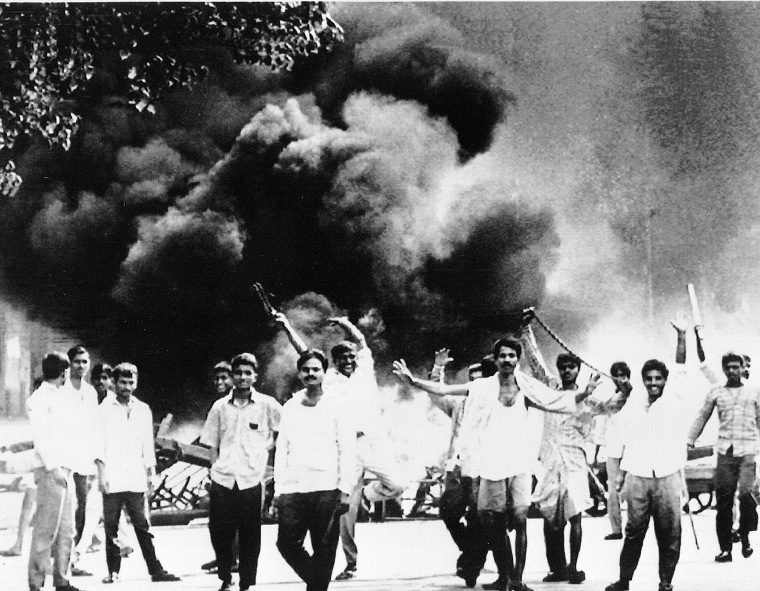

That's what's happening right now. And it is disrupting a lot of our politics. You see virulent, reactionary, in some cases, essentially proto-fascist movements against immigrants popping up all over the developed world. And not just in the developed world. I mean, there are riots against refugees in places in the developing world. It's not simply in a place like Poland or in Hungary. You're seeing it in Turkey right now, where the Syrian refugees in Turkey are a major political issue. In fact, the new mayor of Istanbul largely campaigned on and ran on all sorts of promises to get rid of Arabic signs in the city.

So all around the world we're seeing huge amounts of people moving and huge disruption to politics around that migration. And in a lot of ways this is going to be the central challenge for us, in this century. I really, truly believe that. The central challenge is climate and making sure that we have a habitable planet and we don't cook the earth past a kind of disastrous tipping point. But embedded in that is the fact that a lot of people are going to move to a lot of new places and we are going to have to figure out, as societies, how to create stable, equitable, welcoming, multiracial, multiethnic, multilingual democracies that give dignity and equality to the stranger.

The best traditions of America are that. I mean, America really is a unique place in its immigration history. It's a place in which on the ashes of ethnic cleansing and dislocation of Indigenous populations, and on the backs of slavery, a society was built that also produced a kind of creedal nationalism that welcomed all kinds of different people from all kinds of different places.

The welcoming was really fraught in a lot of places. There were all kinds of reactionary anti-immigrant groups. There's a piece of legislation literally called the Chinese Exclusion Act. Which, I mean points for accuracy, you can guess what the legislation does.

There are these two strains in America. There is the legacy of white supremacy, oppression and dislocation of Indigenous peoples, and the sort of pure evil of that. And there is in fits and starts, in ebbs and flows, at different moments through this process of extremely difficult trial and error and social mobilization, a vision of a real welcoming and multiracial democracy.

And that's like, in some ways the project of this podcast, is to talk about that. But it's also the project of today's guest, who is an incredible guy, incredible author. His name is Suketu Mehta, and he wrote essentially a kind of manifesto about his vision of America, welcoming the stranger, what it means for America to appeal to the better angels of this nature, with respect to immigration.

He lived it. It's called This Land is Our Land: An Immigrant's Manifesto. Suketu immigrated here as a teenager, as you'll hear, from India. But he's a New Yorker and American through and through. He wrote an incredible book about Mumbai, Bombay, that's called Maximum City, in which he moved his family there and wrote this just mind blowing book about how wild that city is, which I would recommend to you.

He is working on, and has been working on, I think, for more than 10 years, a similar book about New York City, which I cannot wait to read. In the interim and in the Trump era, he said he felt compelled with his distinct and unique perspective to write a book, a manifesto, a sort of cri du coeur about America as a land of strangers, and how beautiful and sublime that is and can be, and what that means, and how much right now that is being threatened and imperiled by Donald Trump and Donald Trumpism.

Suketu, where are you from? That's the question, right? I'm starting with the most loaded of questions.

SUKETU MEHTA: That's the question. Exactly. Where am I from? The planet Earth. The mother ship. Well, I was born in Calcutta. My mother's from Nairobi. I grew up in Bombay. And when I was 14, I came to Jackson Heights. So, I used to answer this question, "Where are you from?" growing up in Queens I'd say, "From Bombay." But increasingly now, when I go around the world, I say I'm from New York. I lived in Queens. I've lived in Brooklyn. I now live in Manhattan. So yes, I'm from the planet Earth.

CHRIS HAYES: When you came with your family, you've described some of this in the book, it's actually a harrowing moment when your mother's passport is basically rejected. You'd fly through Germany to come to New York, and your mother's rendered a stateless person at the border because she has a passport that had been issued to subjects of the British Empire in Nairobi. But you end up here.

What's your recollection of that experience? I've got a very good friend who grew up in Russia and immigrated when she was 10, and other friends who came here. It must be such an intense experience.

SUKETU MEHTA: So you know, it was better than coming across the Atlantic Ocean, and Jains were traveling in steerage. But we had this very strange experience where we all had Green Cards. Or we were supposed to be ... We were approved to come and stay in the United States and live here. Our Green Cards we're waiting for us at the JFK airport. I was 14, my sisters were seven and two.

And we just had to transit through Germany from Frankfurt to Cologne, and then get on a flight from Cologne to JFK. But at the Frankfurt Airport, the German passport control officer looks at my father's Indian passport, and mine, and my sisters' Indian passports, and we're fine. But my mother's British passport, it was a passport given by Great Britain to citizens of the former Commonwealth, that basically had no value. You couldn't take the passport and live in the country which was issuing that passport.

CHRIS HAYES: You couldn't go to Britain?

SUKETU MEHTA: You couldn't go to Britain. And-

CHRIS HAYES: It's just like, "Here's a document."

SUKETU MEHTA: Exactly. It has your name on it and if you need a passport, "Here, take this and make of it what you will." So then the passport control officer looks at my mother's passport and says, "Sorry you can't transit through Germany."

So we had to figure out what we were going to do now because my mother was essentially a stateless person in Germany. It was kind of humiliating for us, this little family looking to get to America. And I don't understand what the passport control officer was thinking. Was my mom just going to make a break for it and live by herself in Germany while the rest of us went to America? It made no sense.

So then we ended up going on an Air India plane that happened to be leaving from Frankfurt to go to New York. And we were all bundled on this plane. I remember on this plane as we get in, there was this drunk guy who had gotten on at Delhi, and the stewardess shakes the guy who sleeping and says, "Sir, where are you getting off?" And he says, "Huh? Where am I?" She says, "Well, you're in Frankfurt." He says, "Oh my God, I need to get off here."

If we hadn't gotten on the plane, he would have stayed on the plane and woken up in New York. So it was an absurd journey throughout. And then when we get to JFK, our first apartment in the country was a studio apartment in Jackson Heights, and there were five of us crammed in this studio apartment. And the super turned off the lights the first night because there were too many people in the studio apartment.

CHRIS HAYES: This was his way of being like, "I don't approve of how many people you have packed into the apartment I'm renting you."

SUKETU MEHTA: Right. Exactly. Yeah, yeah. He was.

CHRIS HAYES: So you won't get electricity.

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah, no electricity. Which didn't bother us because we were from Bombay where the lights went out every night. We were home.

CHRIS HAYES: Joke's on him.

SUKETU MEHTA: I remember going out to Roosevelt Avenue and looking at the elevated number seven train, this rusty train and this strange half yellow light of the New York streets and wondering, "Where is the Statue of Liberty?"

CHRIS HAYES: What was the first period of time for you as a teenager — which is a hard time for anyone in any situation if you're in a completely homogenous environment in a small town, or like me, if you grew up in New York, which I did, and traversed the city — it's hard. You're looking to fit in any way. What was that like for you?

SUKETU MEHTA: So my early years in Jackson Heights were really miserable. My parents put me into the nearest, what in India we might call a convent school. So it was a Catholic school.

CHRIS HAYES: Catholic school, yeah.

SUKETU MEHTA: Because the Catholic schools are the good ones in India. And they put me into the nearest Catholic school, which was this extravagantly racist institution. It was this all-boy school where I was among the first minorities. I was the meat thrown to the lions.

I remember my second day in this school, this white kid with red hair and freckles, coming up to me and glaring at me and saying, "Lincoln should have never let them off the plantations." And I said, "But what's that got to do with me?"

CHRIS HAYES: Wow. Wow. Wow.

SUKETU MEHTA: It was his way of saying, "Welcome to America."

CHRIS HAYES: That was the opening line, "Lincoln never should have let them off the plantation?"

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah.

CHRIS HAYES: In New York City in 1977.

SUKETU MEHTA: 1977, exactly. It was-

CHRIS HAYES: In Queens.

SUKETU MEHTA: In Queens, home of the current president.

CHRIS HAYES: That's right. Queens that gave us Archie Bunker and Donald Trump.

SUKETU MEHTA: Exactly.

CHRIS HAYES: And this boy. And there's a relationship between those three. I mean-

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah, Queens, the most diverse county in the United States, statistically, also home of the least diverse human being in the country. But this is why I feel like I really understand Trump's makeup, because I grew up in this place where the father of the kids I went to school with were essentially Donald Trumps. East Elmhurst, where my school was located, was this white enclave, working class white enclave, which was steadily being encroached upon by all these minorities. Indians, Bangladeshis, Colombians, God knows who. And for these-

CHRIS HAYES: Renting studios with five people in them.

SUKETU MEHTA: Right, exactly. With the strange-smelling foods, and their Bollywood songs. So the school was ... I mean the teachers called me a pagan. I mean, I had to run for my life many days of the school day.

But the building that I grew up in was quite another story. So we had people from all over the planet. We had Indians and Pakistanis. We had Haitians and Dominicans, the Russians, the Jews, Muslims. The super was a Greek, but the building was owned by a Turkish man. These were all people, Chris, who were killing each other just before they got on the plane.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah, the Pakistanis, and Indians, and Turks, and the Greeks, right?

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah, exactly. Here we are living in the same building, and the only thing we had in common was Sunday morning. There was a TV station, a Spanish language TV station, WNJU from Linden, Newark, which broadcast a Bollywood musical program called Vision of Asia, Sunday mornings. And the entire building, the Indians, Pakistanis, Dominicans, Russians, all sang along to the Bollywood songs. Because that's the one thing we had in common.

Now, it's not that we all loved each other and understood each other. It wasn't a paradise of racial tolerance, but we agreed to suffer each other. We all said extravagantly racist things about each other when we got back into our homes. "Oh, these Pakistani, if they eat all this meat, how can ..."

CHRIS HAYES: I mean, it's funny you say that because the cosmopolitan nature of New York City exists side by side with incredible amounts of racial stereotyping and ethnic stereotyping, from every group to every other group. Right? I mean, I remember ... in the Bronx, there's a lot of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans — Dominican friends about Puerto Ricans saying wild, crazy, obviously false stuff. Generalizing about Puerto Ricans all do this. I'm like, "I don't think that's true." Or like, Dominicans don't wash their clothes. I'm like, "That's not true. Of course they wash their clothes. What are you talking about?"

But these stereotypes, these sort of ethnic group stereotypes were so powerful, and it is a weird way that those sit aside the kind of agreeing to suffer each other. That is what a functioning, tolerant cosmopolitan society or city looks like.

SUKETU MEHTA: It's really quite marvelous. The Jewish Center in Jackson Heights ... there used to be a lot of Jews in Jackson Heights until the 1970s, 1980s, when they started going out to the suburbs ... so it's the community center with a lot of space. The Jewish Center of Jackson Heights hosts the annual Iftar celebrations for the Muslim community there. Because there isn't enough community space, so the Jews will happily let it out to the Muslims, to the Christians. So the clash of civilizations makes a joyous sound in Jackson Heights.

CHRIS HAYES: Okay, let's zero in on this a little bit because this gets to sort of the broader themes of your book. One of the things I like about the book is it moves between the particular and the universal. This desire to move to new places happens all over the world in all sorts of conditions. And fear and resentment of the new person coming in happens in all kinds of places. I mean, you mentioned this in the book. Like Bangladeshis coming over to India, subject of tremendous, terrible, sometimes violent xenophobia. Right now there's incidents in South America where Colombians have taken to the streets to protest against Venezuelans who are there from next door.

What's the recipe? What makes the culture work when these fear, resentment of the stranger is so universal? And even in the multicultural little apartment complex, what's the difference between the world that's instantiated there and the world that's instantiated in your Catholic school, where you are the subject of really nasty, racist bullying?

SUKETU MEHTA: Well, I think Jackson Heights points the way forward. The reason Jackson Heights works is because no one community predominates. You can't scapegoat say, Dominican or Indians because there's plenty of Dominicans and Indians and everyone else, Russians, Poles, Chinese, you name it. So that's one answer, not to cluster immigrants in these ghetto. Another one is, there were people in my building who would have liked to beat up other people because of their ethnicity. There were kids who called each other all kinds of racist names, but they also know that in this country, or at least in New York City, the hate crimes laws are enforced.

My sister, who was also bullied and beaten up in her elementary school in Queens when we came here, she grew up to become an assistant district attorney in Queens, and she was prosecuting hate crimes after 9/11. So there has to be a recognition that you could have really bad impulses, but you can't act on them because you will be held to account.

Now, this was not true in South Asia where I came from. I've written a book about Bombay, in which I write about how Hindus slaughtered Muslims with impunity in the 1992 and 1993 riots in Bombay. And I actually spoke to these murderers and they walked around the streets completely unpunished. The political leaders were unpunished.

CHRIS HAYES: The man that runs the country now.

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah, that's right.

CHRIS HAYES: Essentially someone who, in previous roles, incited this kind of violence.

SUKETU MEHTA: In 2002, there was an anti-Muslim pogrom in Gujarat, which Narendra Modi, who's now the prime minister, he was chief minister of the state during the time and did absolutely nothing to stop these rampaging mobs. In fact, there are indications that he moved the state machinery to assist these mobs.

So it's not enough to say, "You guys can live here and everyone's welcome." The legal machinery has to be in place to stop people from acting on their worst impulses.

CHRIS HAYES: What is your observation? In some ways, I think you say this in the book, it sort of forms the inspiration for writing the book, but the trajectory of immigrant life, understanding of immigration's role in the U.S., over the trajectory of your life, from the time you were 14 in 1977, to the Trump era.

SUKETU MEHTA: So I went to this Catholic school in Queens and somehow survived it, and then went down to NYU. But my parents were afraid I'd be Americanized if I lived in the dorm, so I had to stay home and commute from Jackson Heights to NYU. And now I said, "I'm getting into NYU housing one way or the other." So I'm an NYU professor now and I go to-

CHRIS HAYES: You showed them.

SUKETU MEHTA: Exactly. I have do the reverse commute because I go to Jackson Heights to study those people, so I'm in a glorified NYU dorm, but every year that I was here, since 1977, I became more and more confident in my place in the country. And whenever I'd go abroad, I've lived in Paris, I've lived in London, I've lived in Sao Paulo, I went back to Bombay for two and a half years to write my book, and I'd feel this gladness when I came back to America, when I saw-

CHRIS HAYES: Visceral.

SUKETU MEHTA: Absolutely. When the plane would go over the Long Island, a view would come in, and you look at it and then you're descending into JFK, which is not an aesthetically pleasing airport, but still you feel great to come out, and there was some cabby from Uzbekistan or whatever who'd take your bags. Each time I came back to America, I felt happy and I felt more and more like, "Yeah, this is my place, America, New York is the last home for those who have no other home."

Until 2016, that horrible, bleak November day. My students at NYU were weeping on the streets, and there were all these people assuring us, "It's all right. Trump may have said extreme things during the election, but now he's president, he's got to be presidential. Every president has to be a president for all Americans." That's the day it really changed, and since then, since 2016, with every month, I've felt my position in the country being openly challenged.

Those kids in my Catholic School, who threw incredibly racist abuse at me, I realized they now run the country, and they're in power. This is new, and that's why I wrote this book, because I believe in the country, and just like I fought those kids in the Catholic School, going to fight the bigots who now occupy the highest offices in the land.

CHRIS HAYES: Do you experience that firsthand, that feeling? Is that kind of ethereal feeling, or is it a daily experience?

SUKETU MEHTA: I write in the book about an experience I had with my sister year last Thanksgiving. We decided that we were going to get a drink in Hoboken, in New Jersey, because Hoboken had just elected a Sikh mayor. As we were walking across the street, this car pulled up with these young white kids who were just yelling all kinds of things: "Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar," and they were gesticulating and making obscene gestures. I put my middle finger up at them, and this guy jumps out of the car, and he was this very stocky-built white bro. I'm not ashamed to say that he would have beaten me to a pulp. We duck into a restaurant. We called the cops. The guy jumps out but he doesn't come into the restaurant.

But he's still yelling all this abuse at me and my sister. The cops come, and this white cop asks, "What's the matter?" I tell him, I said ... "So, what were they yelling?" I said, "Allahu Akbar." He said, "What does that mean?" I said, "It means God is great in Arabic." He said, "What's wrong with that?" And then I had to explain to him that he thought we were Muslims. He looks at me and my sister and says, "Well, you don't look Muslim. You look Indian." Of course, I had to explain to him that India is the second biggest Muslim country in the world. There's 200 million Muslims, and it doesn't matter if we're Indians-

CHRIS HAYES: Right, yes, missing the point, really.

SUKETU MEHTA: And then he's like, "Well, what were you doing?" I said, "We were crossing the street." He said, "Well, did you press the walk button before you walk the street?" I said, "What? You're going to get me for jaywalking now?" Okay, and it was this absurd encounter, but the point was that there was this car full of kids, again, who could've come from my high school days, the bullies at my high school, and they were yelling the exact same insults. But they felt emboldened now in Trump's presidency, that they felt that this country was theirs.

Even inner city, which was nominally run by a Sikh mayor, they could drive around the streets yelling at people who weren't white. This was new. This hasn't happened to me basically since high school, but it's now happening to me again. It's happening to me all over again now that I hear the president yelling at these four women of color, congresswomen of color, "Go back to where you came from." This is exactly the same phrase that those bullies in my Catholic School used. Go back to where you came from. I did not think I would hear it in America from the president of America in 2019.

CHRIS HAYES: There's something really specific about that phrase, isn't there? I've had, over the last few days, conversations with so many people, African Americans, Americans of different racial and ethnic backgrounds and also immigrants. Everybody has a story of the first time they were told that, and the poison of it.

SUKETU MEHTA: Look, every immigrant group that's come to the country has had this phrase thrown at them. The Irish had it, the Italians had it, the Jews had it, and it hurts. It hurts every time because you come here and you really want to contribute to the country, and you think that this is one place where you can be American. I've lived in England, I never thought I could be English. I've lived in France, I never imagined I could be French. But yeah, this is America, and I was told, and this is the foundational myth of the country, that it's a country of immigrants. You can come here and be American.

But there's also this other side of America, which is where people get told, "You don't belong here. You're not like us." I, literally, am reminded of a gentleman named Ben Franklin, who in 1751 writes about the alien menace that is invading Pennsylvania at the time.

Quote: "Why should the Palatine Boors be suffered to swarm into our Settlements, and by herding together establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our complexion?" He's talking about Germans, the ancestors of our current president — Palatine Boors indeed.

CHRIS HAYES: What's so remarkable about this, and this came up in a conversation with Patrick Radden Keefe, who I think he's a friend of yours, was on the podcast, and you're reading about Northern Ireland, right? All ethnic and racial hatred from enough distance looks preposterous. Ridiculous. It looks like the Dr. Seuss, which side of the bread you buttered on. That's comical, like what the hell are you talking about?

But of course that's true with everything. Every single one of them, every single one of them, a culture you're embedded in where it seems wrong or vile, but not preposterous, is as preposterous as that statement. Every bit of ethnic stereotyping, bigotry, hatred, tribal, confessional, whatever it is, is literally that preposterous. But it doesn't feel that way to people in the moment, to huge swaths of people. Even very wise and smart people like Benjamin Franklin.

SUKETU MEHTA: This is why I think that the best way to fight at this kind of bigotry is stand-up comedy to really show it for how preposterous it is. At some point it gets so bad that it becomes funny, and you have to mock these people. But it's not funny when these people hold the levers of power, who they can actually do something about it. They can change the laws so that not just legal immigrants, but naturalized citizens can be unnaturalized if the Justice Department has a task force to go after naturalized American citizens now.

I don't know if those laws could be used against people who disagree with American policy. There's all kinds of really crazy thoughts running through every immigrant’s head right now. This kind of paranoia. But paranoia is not paranoia if it's justified.

CHRIS HAYES: Yeah, my therapist calls it catastrophizing.

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah.

CHRIS HAYES: The sort of thinking of the worst case scenario, but that's an entirely rational set of mental exercises to do for so many communities right now.

SUKETU MEHTA: Well, these ICE raids that are now supposed to defend across the country now. I know people, I know undocumented families, and I know undocumented, semi-documented, and fully-documented families all living together. So, they could be like a family in which someone doesn't have papers, someone is going through the process of getting papers, someone already has papers, someone is already a citizen. But if the state comes knocking at your door, and you let them in, they're going to arrest everyone.

So, all across community like Jackson Heights, through much of New York, there's this kind of fear of the state of the midnight knock, which is like Stalinist Russia. I never thought that we'd see the country come to this path.

CHRIS HAYES: I want to drill down on what I think is a really interesting philosophical tension in your book about people's right to move. Let's talk about that right after this.

You talk about, and I think I may be knew this somewhere but had not really remembered it or meditated on the fact that part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is adopted by the United Nations. And sort of the founding set of documents is that people have the right to move. So, a really important fundamental right is that you can leave the country you're in. We all recognize that, right? Why is the wall there in East Germany? It's not there to stop people from coming in. It's there to stop people from leaving.

We all understand that a country that stops its people from leaving, say North Korea, is just definitionally tyrannical. You can leave if you want to go, right? But then there's like, "Well, okay, well, if you leave you've got to go somewhere, right?" There's also embedded in that document the right to petition for political asylum. There isn't quite the right to go anywhere you want. Should it be the case that it is a universal human right to pick up and move to the country of your choice?

SUKETU MEHTA: But that's the question of open borders. Does the nation have the right to control who comes in, how many they let in? It's a very complex issue. I'd like to first point out that this whole question of borders and passports and visas is only about 100 years old. In the long history on the planet, we human beings have only started thinking about these questions about a century ago. Before that in the age of mass migration from the middle of the 19th century to around 1914, fully one quarter of Europe up and moved to the United States. What happened? The Republic did not collapse.

CHRIS HAYES: No, in fact the opposite. It was part of what converted it from sort of a colonial backwater into a super power.

SUKETU MEHTA: Exactly, the U.S. eclipsed Europe at the pinnacle of world wealth and power because of it had an open border policy.

CHRIS HAYES: Not only that. This is my favorite fact, and you write about this in the book. When people say, "Well, my ancestors came legally." It's like we had open borders. They came legally because literally there was one rule: no Chinese.

SUKETU MEHTA: Right.

CHRIS HAYES: It's called the Chinese Exclusion Act, and it had a quota on the Chinese and everyone else, it was like, "Come on down."

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah.

CHRIS HAYES: That was the legal posture of American immigration policy for decades.

SUKETU MEHTA: So, in my book I also considered these arguments by serious philosophers, not just crackpots, who say that any kind of collective has the right to define rules for membership, or there's this lifeboat here. The United States is a lifeboat in an ocean, and there are lots of people swimming around. If too many people get on the lifeboat, then everyone sinks — both the newcomers on the lifeboat and people who've been there before. And so, I've considered these arguments, but I really can't find any evidence that, if tomorrow we were to suddenly open up our borders, and there's a lot of people who'd like to move to the United States.

Well, first of all, GDP would increase enormously. There's a statistic that if the world had open borders, then world GDP would increase by $78 trillion a year. When people move, everyone benefits. If the United States were to adopt a policy, let's say, short of open borders. For every one million people that we bring in, the GDP will increase by 1.15 percent. So, there's just no doubt that immigration benefits the countries that the immigrants moved to, particularly the rich countries because we're not making enough babies, and we need young motivated immigrants to work because the United States by the middle of the century is going to be a nation of geezers. As the baby boomers retire, there's not enough working age adults to pay for the pensions of the old people.

CHRIS HAYES: If you want to see the future of America, go to a big facility for seniors, particularly in a metro area like New York, assisted living where it is like old white folks being cared for by 30-year-old immigrants and people of color. That's it. That's it. That's the future of the country in many respects.

SUKETU MEHTA: That's it. Look, the replacement rate is 2.1 babies per woman. The United States' replacement rate stands at 1.7 babies per woman. You see this around the world, Japan. Under 4 percent of the Japanese population is foreign born. It's ridiculous.

CHRIS HAYES: It's one of the most closed off society to immigration of any, probably it is the most closed off to immigration of any First World country.

SUKETU MEHTA: Exactly, yeah, because they want to keep their culture pure. As a result, the economy has stagnated, and in the villages of the north, there's only old people left because all the young people have moved to the cities in the south. They've been invaded by wild boars from the mountains. So, it's a common sight to see these old men and women being chased by wild boars in the villages. The Washington Post had this fascinating article about this, where old Japanese people are being menaced by wild boars because there's not enough young people to chase off the wild boars.

Is this what we want for our country? Wild boars chasing our old people? Bring in the immigrants. Well, the Japanese also have realized that they need more immigrants because they need labor. So, they're actually very cautiously opening up their doors. They're trying to recruit high-skilled immigrants, but not enough people want to move there because they feel it's a hostile atmosphere for them.

CHRIS HAYES: But I have to say that the economic argument always leaves me a little cold, right? It just sort of feels like it's a hard thing to persuade people of. It always feels a little like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is trying to sell me on something when I hear this argument, which I think is backed up by the vast majority of economists and wonks with a small dissenting group of economists and wonks.

SUKETU MEHTA: Yeah, there's basically one man, George Borjas at Harvard.

CHRIS HAYES: George Borjas, who's the famous contrarian on precisely this. He's the guy that you will see cited in every bit of literature and pamphlets from this anti-immigration coalition. I guess what I'm trying to get back around to is the basic moral principle. There are times when I think to myself it seems possible to me there's two things I feel it's about, eating meat and immigration, where it seems possible to me that in 100 years people will look back on the current policies as like obviously barbaric.

That it just makes no sense that just the natural lottery of where you happen to be born essentially determined all your life outcomes, and like if you're born in a slum in Bangladesh, like, "Too bad. Got to stay there. Can't go to the United States, because you’re SOL buddy." At some level it's like that's morally indefensible. Why is that the case? It shouldn't be that way, and yet it's crazy and radical to say like, "No, they should be able to come here because then where we have a billion people who move to the U.S., right?" There's all these sorts of catastrophizing thoughts we have about what that would look like. But I don't know, maybe that's right. I don't know.

SUKETU MEHTA: The central point of my book is a moral argument that all these people, and you're right, the greatest inequality in the world today is the inequality of citizenship, a disadvantaged lottery. I can predict a person's life depending on the passport that he or she holds. But the question I ask is, "Why is it that Bangladesh is in the state it's in right now?" The nation that's caused Bangladesh's misery, the United Kingdom and Europe, and the United States because of climate change.

Why is it that these Bangladeshis have to endure what they're enduring, which is the possible extinction of their country by the end of the century because of climate change. It's not their fault. They are coming here because we were there. The British went into South Asia, stayed there for 200 years, and destroyed the economy. When the British arrived in India at the beginning of the 18th century, by India I mean all of South Asia, India's share of world GDP was 23 percent. By the time they left, 200 years later in 1947, India’s share was four percent of world GDP.

So, basically the colonial empire will run for the benefit of England and France, who together made the 40 percent of all the borders in the world. Bangladesh is in its current condition, because first, the British looted it, prevented it from building up its industries. Now, we're worried about four million Syrians going into Germany because of the law. What happens when Bangladesh get flooded, and 400 million Bangladeshis have to find dry land? Where are they going to go?

CHRIS HAYES: Well, here's the thing. This is super crazy. They're going to go to India and Pakistan.

SUKETU MEHTA: Right.

CHRIS HAYES: This is what's so wild. The U.S. barricading itself behind the walls, when you ... Colombia has got a million Venezuelans, a million. Can you imagine if a million folks showed up? We're freaking out because several hundred thousand a month are showing up at the border from all of Central America. There were several million Iraqis in Damascus alone at the worst periods of the sectarian civil war in Iraq, in one city. It creates lots of tension. There's lots of fights. There's the Mayor of Istanbul is on a new crusade to get rid of Arabic signs, because there are so many Syrian refugees in Istanbul.

But the level of migration between developing countries and refugee populations at developing countries are constantly asked to take in, and the burden they bear from Jordan to Colombia to India to all across the developing world, for the First World to be like, "No, this is outrageous," it's crazy. It is crazy.

SUKETU MEHTA: Exactly. The vast majority of world migrants, 85 percent, moved from a poor to a slightly less poor.

CHRIS HAYES: That's right.

SUKETU MEHTA: We think that there's always the right wing — if you're to look at Fox News you'll think, "Oh, my God, we're so generous. We let in a million migrants.” We rank 23rd in the world in terms of how many immigrants we let in as a percentage of our population. If we tripled our intake, we won't even be in the top five. Even among developed countries, Australia, Canada, they take in far more immigrants than we do. Germany takes in far more immigrants than we do as a percentage of the population.

America is no longer a nation of immigrants. Officially, we're no longer a nation of immigrants because that phrase was removed from the Citizenship and Immigration Services website earlier this year because the Trump administration doesn't think of the country as a nation of immigrants.

CHRIS HAYES: So, I want to make the argument, the argument that restrictionists make. I've spent a lot of time going back and forth with these people and reporting on immigration, so I feel like I can give their arguments. The argument that restrictionists make, and I would choose the kind of most enlightened of them, and the least racist — Reihan Salam is one, who's got a book out, who himself is a child of Bangladeshi immigrants, a friend of mine, and someone that I like and respect — is more about sort of national character and also this argument about periods of big flows followed by periods of small flows. Right?

So we had this huge burst, as you say, and then 1914. And then there's a long period in which there's very little immigration relatively. It lasts until basically the 1960s Immigration Naturalization Act, INA. So you've got about 50 years where the idea being that, look, it's hard to bring different groups together if you've grown up in an apartment in New York you know there's some friction. And you need this period of homogenizing where everyone can kind of all Americanize together.

But if you keep adding to the mix and you keep bringing in new people, you're disrupting this process that's important to the civic binding. It's like you're not letting the concrete set.

SUKETU MEHTA: Right. I'm familiar with this argument and it's hogwash. Look, New York City's exhibit A in showing that immigration works: New York City is now at historically unprecedented levels of number of immigrants it takes, even as a percentage of its population is approaching the highs of the early 20th century. Two out of three New Yorkers are immigrants. New York has never been richer. New York has never been safer.

There's no evidence that these alleged waves of immigrants are actually disturbing the peace, or else making people poorer. However-

CHRIS HAYES: But the argument is that New York has never also been more unequal, right?

SUKETU MEHTA: Right.

CHRIS HAYES: There's a connection between that. You basically have huge swaths of a constantly growing pool of cheap labor that comes in the form of immigration, and then a bunch of plutocrats at the top, and that's the system they want to set up.

SUKETU MEHTA: Right. But the inequality wasn't caused by the immigrants.

CHRIS HAYES: Right.

SUKETU MEHTA: The anti-immigration backlash is something that the plutocrats use. And this is, I have a whole chapter in my book, and it's the phrase that Hannah Arendt uses, the alliance between the mob and capital.

I took a trip in that dread year in the summer of 2016, a road trip from California to New York. And I went through industrial Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, Trump country. And I remember going into this factory town called Warren, Pennsylvania. And this was a place where this one company, the Blair Company that made raincoats for American GIs during the war, basically employed everyone in the war.

Now when I walked through it in 2016, it was a zombie town. There were young white men and women in this empty town stumbling through the streets at noon, and they were basically hooked on opioids. The only industry left there was either the drug trade or the military. So these people had been gobsmacked by automation and the loss of jobs. And they were angry. Most of them voted for Trump. And they were wondering like what happened to their money?

Steve Bannon once said that the origins of the current way of nationalism, not just in America, but in Europe, originated in the 2008 financial crisis. Now, I don't agree with Bannon on much, but this is one thing where I feel he has a point. These people's money was stolen, and where did it go? To the plutocrats, it went to Wall Street. The government bailed out the bankers. America has never been more unequal. The top 1 percent make more than the bottom 90 percent.

But the plutocrats, the rich being no fools, knew that the peasants were coming for them with pitchforks and if they didn't direct the rage away from them, then all hell would break loose. They'd lose their Porsches and their fancy condominiums. So they directed the outrage away from them and onto the newest, the weakest, the immigrants.

CHRIS HAYES: See, I think that part of that story is true, but I think there's part of that that's not true, because I think part of it was actually organic. Having covered this, I think one of the things you saw with the Republican Party was the plutocrats didn't like all the anti-immigrant rhetoric. There's even reporting about Rupert Murdoch setting up meetings where the Republicans go to talk to Sean Hannity about like, "Don't do the." Like Murdoch is setting them up, right? Because it's actually bubbling up organically from the base.

You know, the anti-immigrant rhetoric, there are people who are cultivating at the top and Donald Trump is one of them. But it's also a bottom-up phenomenon. People are showing up at town halls and Republicans are getting their hair blown back. Eric Cantor is the perfect example, right? He's the plutocrats' best friend. He's a Wall Street, Republican guy and he loses this shock primary to an insurgent who basically goes after him solely on immigration.

So I think there's, the reason I say that is because one of the things I feel like that we all have to deal with in this era is the universality of that rage, anger, fear of the newcomer, as a human experience that people are experiencing and channeling because we have to deal with it head on and look at it clear-eyed, or it will literally destroy the world. And I mean that literally. It will destroy the world. We will end up in either a world war or we will cook the planet, unless we can figure out how to get people over that fear. Don't you agree?

SUKETU MEHTA: I totally agree that in the beginning to never-Trumpers, the country club Republicans, they had it known that they didn't liked Trump. Once he was in office, he gave them the biggest Christmas gift in history, the tax cut. And now, they're all behind him. And he is planning to get re-elected on the basis of immigrant hatred. This is going to be his signature policy, and all the plutocrats are behind him and they've never been richer.

CHRIS HAYES: But Trump is, as you write in the book, he's part of this broader phenomenon. We've seem it in Poland and Hungary. We've seen it in the UK with Brexit. We've seen it in Italy. Italy is, particularly, a place that I've lived for six months, and is near and dear to my heart, where there is extremely ugly, ugly, ugly anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies from the Interior Minister Matteo Salvini. This is a global phenomenon right now.

SUKETU MEHTA: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. I've gone around the world, and looked at the phenomena in Hungary, Spain, Morocco. I've spoken to all these migrants coming over. So yes, there is populist around the world, whether it's Trump or Orbán in Hungary or Duterte in the Philippines or Erdogan in Turkey or Modi in India.

And a populist is basically a gifted storyteller. Someone who can tell a false story well. And the way to fight them is by telling a true story better. I think you're right, that a lot of the resistance to migration is cultural. People, they're afraid of the country being nonwhite. Most of the people who voted for Brexit, the biggest own goal in British history, weren't people living in London. They were white English people living in rural England. And the people who had everyday day-to-day lived experience of immigrants really liked the immigrants and voted to remain.

CHRIS HAYES: And that's literally the exact same thing in Le Pen votes in France. It's the same thing at Trump votes in the U.S. An absolute iron law of all this is that people who are not immigrants in the most cosmopolitan areas which have the most exposure to immigrants are the most pro-immigrant populations in every respect.

SUKETU MEHTA: Right, like so many other things, it's an urban-rural divide. And the other thing, the other part of my writing career is about cities. The biggest human development of our lifetime is that for the first time in human history, more people are living in cities than in villages. So all across the world there's a stampede to the cities.

CHRIS HAYES: It is the first time in human history. This is important.

SUKETU MEHTA: The first time in human history.

CHRIS HAYES: And in fact the biggest migration in the world is the internal migration of Chinese rural folk to the Chinese cities, right? That alone is the largest internal migration that's ever happened.

SUKETU MEHTA: Right. But there is the backlash to this migration. There is this idea of the city as Sodom and Gomorrah, the city as this entryway to these foreign forces. There's a backlash of homogeneity against heterogeneity. There's huge part of America that thinks that Jackson Heights is not an attractive place to be. They don't want to donate to Jackson Heights. And they don't have to. I've lived in Iowa for three years and Iowa was a perfectly fine place.

CHRIS HAYES: It's lovely, but the food is better in Jackson Heights.

SUKETU MEHTA: The food is much better in Jackson Heights. I went actually from Jackson Heights to Iowa City, from the most diverse county in the United States to the home of the world's biggest hog. And that hog was impressive, let me tell you. It had its own zip code.

But I can completely understand why Iowans might like to keep Iowa what it is. But then they also have to realize that these people who want to come to Iowa, from El Salvador and from Guatemala, they don't want to come there to hang out with the world's biggest hog. They're coming there because we have left them no choice. They are coming to Iowa and to Illinois and to New York because Americans have gone into these countries and ruined their countries for decades now.

Anytime there's been any kind of decent government that could have come up in this countries, the United States Armed Forces have toppled them in favor of malleable despots in these countries. At one point, the United Fruit Company owned 42 percent of all the land in Guatemala. We put 1.8 million guns in Honduras to arm the Contras during the Nicaraguan conflict.

So these countries are coming here, and what I faced formally in my book is that people are moving not because they hate their homes or their families, but because of colonialism, war inequality and climate change. These people are coming here because we have literally made their homelands uninhabitable. So I want to turn the tables on the whole migration debate.

Not ask so much, "Is it good for us Americans to let in immigrants? Should we let in high-skilled or low-skilled immigrants? How many should we let in?" But look at it from the migrants point of view. Why are they moving in the first place? Why would someone take their daughter and their hands and swim across the Rio Grande? Why would someone take such incredible risks for their children?"

Like that the horrific photo of that father and daughter who were drowned in a Rio Grande. I looked into that story. They were working in this minimum wage jobs in this fast food places, and there was no life possible for them in El Salvador. As climate change really kicks in, this is you ain't seen nothing yet.

CHRIS HAYES: No. This is what, I'm obsessed with this because I think people under-appreciate that we're on the front edge of what will be the largest migrant... We're already seeing the largest migrant flows in the history of the world. But they will increase exponentially as climate disaster hits with unequal force in different parts of the world, and particularly hits the hottest places, which are also the least developed places, which are also the most exposed places.

SUKETU MEHTA: And also the least responsible for the climate crisis.

CHRIS HAYES: And the least responsible in the world.

SUKETU MEHTA: Americans are four percent of the world's population, but we put one third of the excess carbon in the atmosphere. The EU, another quarter. It's our responsibility. So if you're not going to let them in, the least you can do is flood these countries with aid for them to stay down on the farm. There's a giant moral bill that is due to the West, and it's a bill that can be paid one of two ways. Either we pay them what they're owed in terms of reparations or we do the reparations another way — we let their people in. And when we let the people in, everyone benefits.

We benefit because we're not making enough babies. They benefit because it's the difference between life and death literally for many of them, and the countries that they move from benefit because remittances are the best and most targeted way of helping the global poor. This is the money that people in Jackson Heights, they go to these gyro stations, and they send back $100, $200 to their grandmothers, to their children, to their cousins for medical treatment, for education to build a small home.

So when people move everyone benefits. But it'll take some time for people to get accustomed to this culturally, in the receiving countries. And I think that's the argument that the restrictionists make about a kind of cultural accommodation. And there are ways to deal with that as well.

CHRIS HAYES: So there's two ways, I think, to look at where we're at. And I think that your book lays this out starkly, right? One is the optimistic way, which is the California example, right? And it's based on both history and the fact that, as I said earlier, places that have the most exposure to immigrants are the most pro-immigrant. Right? So, you know, it's only a matter of time when you get to know them, you love him. Right?

SUKETU MEHTA: To know, know, know them is to love, love, love them.

CHRIS HAYES: That's right. And so California went through this. It had a lot of immigrants. It had this massive and ugly nativist backlash. It had a Republican governor who aligned himself that nativist backlash. And that nativist backlash won a small temporary victory that led to long-term strategic defeat, that basically took California from being a swing state and actually the birthplace of a certain kind of conservatism, Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, etc., to being a permanent super majority blue state democratic one.

So that's one idea, right? That we're just inevitably heading in that direction. And this is the last gasp, it's a dead cat bounce. The other is that we're in the global situation that is in 1935, 1936 where proto-fascist forces are gathering strength as populist movements of reaction across the western world that will inevitably lead to conflagration. Which is it?

SUKETU MEHTA: Both. They've definitely incredibly alarming things happening in Europe. I've been traveling around there and yeah, the Fascists are coming back to power, and in this country as well with the rise of the alt-right.

There's this one number which strikes fear into the hearts of the alt-right here, which is 2044, which is when the country's slated to become majority minority. But then what does the term white mean? And what's it going to mean by 2044? Is Obama half-white or half-black? I never understood that concept of white and black in this country.

When I first came to the country, I had to tick off Caucasian on my census form. So there wasn't a separate category for Asian Indians. And my ancestors would have been gladdened to know that in this country we were actually Caucasian and not brown or you know. Finally we could be white too. And with the rate of intermarriage that we're seeing, it's accelerating, is that this whole concept of race I think is going to matter less and less. But it's a cultural construct.

I think that the way to deal with this is to recognize that there are communities who are genuinely impacted. So, for example, the high school dropouts, or communities along the border. So the way to deal with it isn't to restrict immigration, but to keep more people in high school, to keep more of the native born in high school, and the communities along the border whose schools and budgets are being affected.

There should be an expansion of the earned income tax credit. And also a tax or a levy on the companies that benefit by immigration. So the tech companies, for example. There should be some sort of fee that they pay, which could be directed towards those communities along the border who definitely are suffering, and that goes into their schools, into their hospitals. And it's something that the tech companies could actually be convinced to pay because they depend on immigration for their business.

So there's intelligent ways to do it but we're not having an intelligent debate. It's all heat and very little light. There's no hope of any kind of immigration bill passing through Congress anytime soon. So we're just going to have a bitter, drawn-out fight in the courts. And also in the public space.

Stories help. People don't respond to numbers. I've got lots of numbers in my book. I've got 50 pages of footnotes because I want my stories to be backed up, but ultimately I wish every American could go to this place I went to on the Tijuana-San Diego border. It's called Friendship Park. It's a little park where there's a fence. And it's the only place along the entire southern border where, if you don't have papers and if you miss your family who's on the other side, you can go there on weekends and the Border Patrol will let you go there between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. on weekends to look at your family.

You can't really hug them because there's a rusted iron fence between you and them. But there's these little holes in the fence where you can go up and your mother, who you haven't seen for 17 years, can come up to the other side of the fence. And you look at her and you see her face and you smell her, you feel her breath and you tell her how much you miss her. And then she puts her pinkie through the hole in the fence because the hole is only big enough to put her pinkie through, and you put your pinky through. And you have what they call the pinky kiss. And in that touching of pinkies, you communicate all the love and longing that you have for your mother.

I spent two weeks in Friendship Park, and it was most heartbreaking place. And it's also an affirmation of family like I've never seen. Anyone who doubts that immigrants have family values, anyone who thinks of immigrants as criminals or rapists, should go down to Friendship Park and see all these families doing that pinky kiss. And it'll change hearts. I'm not calling for open borders in my book. I'm calling for open hearts.

CHRIS HAYES: Suketu Mehta is the author of "This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrants Manifesto." He also wrote a remarkably wonderful book called "Maximum City," which is about a Mumbai, Bombay. It's so politically loaded. The Mumbai, it's like a weird, right, it's like a weird BJP thing, isn't it?

SUKETU MEHTA: It could be both. I call it Bombay when I'm speaking English, I call it Mumbai when I'm feeling speaking Gujarati and Hindi. It's a city of many names and any of them is fine.

CHRIS HAYES: It's a great book. You should check that out, "Maximum City." Suketu, thank you so much.

SUKETU MEHTA: Thanks so much Chris.

CHRIS HAYES: Once again, my great thanks to Suketu Mehta. Really remarkable guy and like I said at the top, you should absolutely check out "This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrants Manifesto." You should definitely check out "Maximum City" which is just a phenomenal nonfiction book. And I eagerly await his book on New York City.

As always, we'd love to hear your feedback, and we got great feedback after the last show.

Did you hear, by the way, did you hear that part?

We got great feedback after the last show when I gently discourage you from emailing us to relieve the burden of Tiffany Champion, and instead tweet us. And you did tweet us at the hashtag #WITHpod.

Last week we solicited ideas for topics for podcasts about things that are happening in the world. We got a lot of great feedback on that.

This week, I'd love to hear from the listeners what your own migration story is, whether that's a story of your family, maybe that's a story of migrating from one place to another in the United States. Internal migration is migration as well. In fact, it has different legal structures, but people move places for jobs. They go to new parts of the country and then discover new things.

So tweet us hashtag #WITHpod and tell us about what your migration story is. I'd love to hear about that.

Related links:

"This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant's Manifesto," by Suketu Mehta

"Maximum City," by Suketu Mehta

"Why Is This Happening?" is presented by MSNBC and NBC News produced by the "All In" team and features music by Eddie Cooper. You can see more of our work, including links to things we mentioned here by going to nbcnews.com/whyisthishappening.