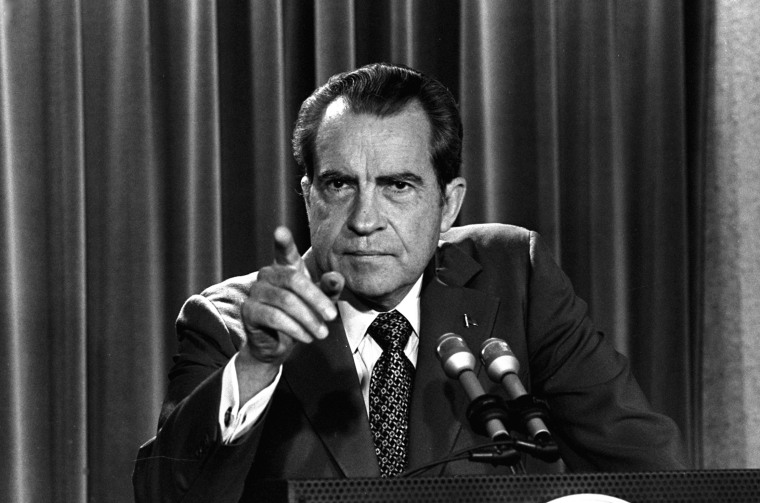

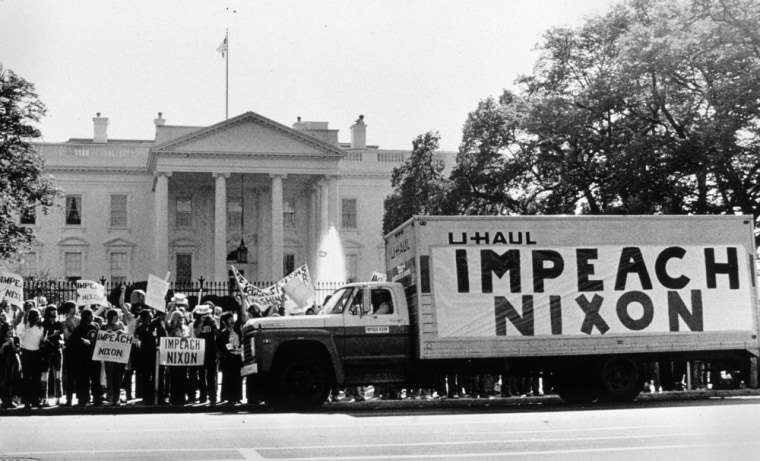

Forty percent of Americans, according to one recent poll, think President Donald Trump’s scandals are as serious as Watergate — the scandal that presidentially disappeared Richard M. Nixon 40 years ago.

This means roughly 75 percent of Democrats (though only 7 percent of Republicans) have been watching the Russian investigation with the same sense of anticipation as kids sitting in the back seat on a long car trip: “Are we there yet?” “No,” say the grown-ups, testily. “Are we almost there?” “No.” “Are we almost almost there?”

Opinion pages, cable shows and office lounges have been filled for months with speculation about whether Trump’s behavior could lead to obstruction of justice charges. His suspect actions include firing FBI Director James Comey, trash-talking investigators and journalists, hinting about pardons and crafting a misleading explanation about his oldest son’s meeting with a bunch of Russians in Trump Tower.

All I can say is: Don’t kid yourself.

Watergate was a Category 5 hurricane fed by a quarter-century of intensifying Nixon-hatred, 10 years’ anger over the Vietnam War and a background of White House misdeeds that Nixon knew put him in personal jeopardy.

Today’s Russia investigation looks more like slimy water sloshing around Trump’s germophobic ankles.

Watergate also culminated with powerful proof: tape recordings showing that the president had ordered a cover-up of the June 1972 break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate building.

What gave the tape such force, however, was that, by the time everyone heard it, the public knew Nixon was heading a vast cover-up. So far, at least, the Russia investigation looks unlikely to yield this sort of irrefutable evidence.

Establishing obstruction of justice can be complicated. You have to find that someone acted “corruptly,” with intent to impede something like an investigation or court case. This is hard to do — unless you know what kind of misdeed the person is trying to cover up in the first place.

So what sort of misdeeds could Trump be covering up? We don’t know. But there’s no evidence yet that he’s engaged in — or even has the imagination to engage in — anything more exotic than garden-variety commercial corruption.

Shakespearean tragedy this is not.

In contrast, many details of the Watergate break-in were clear almost immediately. The burglars were arrested in flagrante delicto. Within hours, D.C. cops and the FBI had discovered the group’s ties to the White House and Nixon’s re-election campaign, and began following the money trail. Were higher-ups involved? Judge John J. Sirica got the answer by threatening the burglars with decades-long prison sentences.

We still don’t know everything, of course. We don’t really know whether Nixon ordered the break-in. No living person probably knows what the burglars were actually looking for. It may be that no dead person knew for sure, either. (Charles Colson, widely considered Nixon’s consigliere, once told The New York Times that the burglars were working for Howard Hughes. Don’t think about that too much.)

The scandal’s juicy parts — Deep Throat, Senate hearings, Saturday night massacre, 18-1/2-minute gap — were all about whether Nixon was involved in the cover-up. At the end, thanks to the tapes, we got the answer. But we still don’t know why Nixon went to such self-lacerating lengths to cover up the break-in.

Let’s leave aside the secondary scandals — like shady campaign contributions — that sprouted like mushrooms from the Watergate muck, and stick to the basics. Nixon had a keen (critics said paranoid) sense of domestic threats, from major anti-war demonstrations to the leaking of the Pentagon Papers in June 1971. That’s when Nixon talked to Colson and White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman about burglarizing — or even firebombing — the Brookings Institution, where one copy of the Pentagon Papers was stored. The next month, the White House Plumbers were born.

The reason the Watergate cover-up followed the break-in so seamlessly was that Nixon himself was involved in some of these previous events.

And the cover-up almost succeeded.

Even after John Dean’s 1973 testimony that he warned Nixon about the Watergate cover-up being a “cancer on the presidency,” the president thought he could just dismiss the former White House counsel as a liar. Nixon was probably right. In July 1973, even after the existence of the tapes became public, some Nixon advisers insisted he could destroy them and survive.

Why didn’t he destroy them? That’s probably the biggest mystery. My late husband, Leonard Garment, who then White House counsel, thought that Nixon couldn’t do it because he saw the tapes as virtually a piece of himself. Destroying the tapes would have been, Len wrote, an “act of self-mutilation.”

In August 1974, after another convulsive year, the nation finally heard the recorded words for which everyone had been waiting. Yet even after we all heard the smoking gun, serious people still counseled Nixon that, if he were impeached, the Senate would likely acquit him.

It’s become a cliché to say, “It’s not the crime, it’s the cover-up.” But the relationship between crime and cover-up is complicated. If Trump took all the actions we know he took against the Russia investigation — he hasn’t exactly been a master of concealment — is that grounds for impeachment?

Our answer would be different if we had direct evidence that he personally colluded with the Russians to influence the 2016 election. But what if we never have that evidence? What if, say, his advisers did but he didn’t know at the time? What if he knew, but didn’t know that it was collusion? Is ignorance an alibi?

What made a third-rate-burglary at the Watergate into "Watergate," the nation’s Ur-scandal, was the combination of Nixon’s underlying consciousness of guilt and his decision not to destroy the direct evidence of that guilt. He knew he was in a trap, but something prevented him from biting off his paw to escape it.

In contrast, with Trump, what we know right now is that, unless many and varied things break in the same direction, we’ll be getting three more years.

So while Nixon may seem the easy analogy, the jury is still out. We’re not there yet. We’re not even almost almost there.

Suzanne Garment, a lawyer, is the author of “Scandal: The Culture of Mistrust in American Politics.”