The death of Stephen Hawking quickly prompted tributes from scientists, celebrities, and politicians, touting the brilliant physicist’s revelations about the nature of the heavens. For the disability rights community, however, his legacy is a little more material. Hawking’s life reveals what can happen when a disabled person receives all the supports they need to live their life to the fullest.

A life like Hawking’s might easily fall into one of two ableist (discrimination or stigma based on prejudice and misconceptions about disability) tropes: The “supercrip” and the body/mind split. In the former, his accomplishments might suggest he “overcame” his disability. In the latter, his disability vanishes from the story as we emphasize the beauty of his mind.

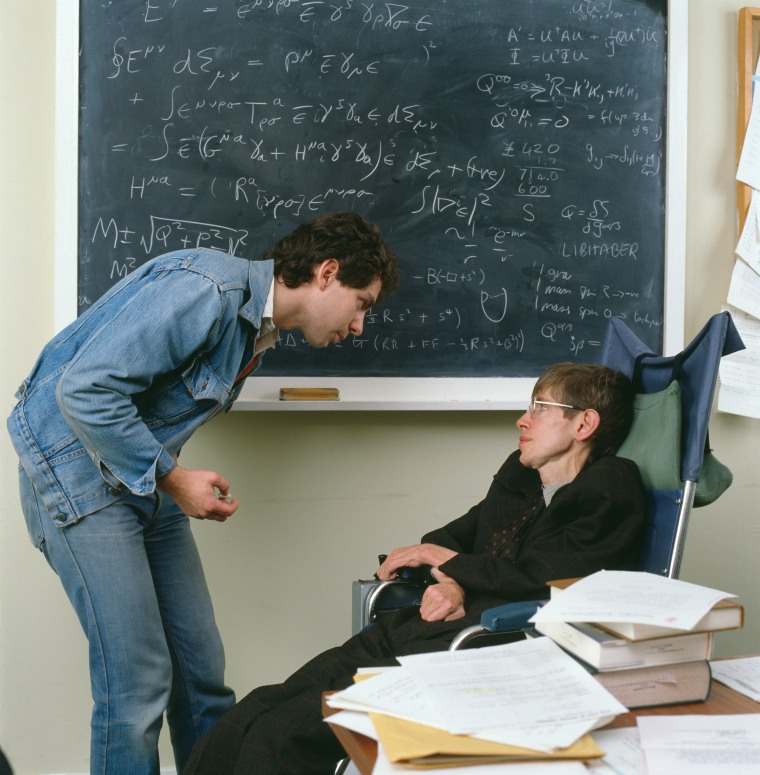

Not only would either be untrue to Hawking’s own words about disability, it sends the wrong message to others. We need to see the scientist as a whole person with a complicated life story. He was a genius, he worked incredibly hard, he had access to great health care and social support, he had plenty of privilege and received help from countless people behind the scenes.

Understanding Hawking starts by shifting our understanding of disability itself, and considering the ways that disability emerges from a complex matrix of social, political, cultural, economic, and biological systems. Societies — people — erect barriers, whether literal physical barriers or those emerging from ableist attitudes and stigma, and create limitations that make it even harder for people less privileged than Stephen Hawking to thrive the way that he did.

Take, for example, the ways that many disabled people are remembering Hawking today. Eb, a disability justice activist, argued that we should understand Hawking as, “An exceptionally privileged white English man who had access to the necessary supports to successfully navigate a world that puts little importance on making itself accessible.” Imani Barbarin, who identifies as a black disabled woman, wrote on her blog, “He never forgot to advocate for disabled people and often lamented the difficulties he faced in the academic community despite his well-known status. We celebrate the life of a man that made it to the stars and worked hard to take us along with him.”

Rick Godden, a professor of English at Louisiana State University, says that throughout his own life, people have tried to tell him that his mind was somehow compensation for his body, rather than understanding him as a whole person. He doesn’t want Hawking — or himself — to be used as inspiration because he "overcame" his body, but “for others who identify as disabled or non-normative in any fashion so that they know they are not alone.”

What’s more, Stephen Hawking himself wrote beautifully about disability and his own success. Writing for the World Health Organization in 2011, he argued, “We have a moral duty to remove the barriers to participation, and to invest sufficient funding and expertise to unlock the vast potential of people with disabilities.” Notice that he’s not talking about cures for disabilities, but removal of barriers to full participation in public life for people who have them.

He also knew that, in both the U.K. and the U.S., right-wing governments are busy erecting more barriers rather than taking them down. In 2008, he defended the U.K.’s health system against American right-wing attacks, by saying, “I wouldn't be here today if it were not for the NHS. In 2017, he castigated the the Tory government for cutting public funding and accelerating privatization. He had planned to go to court to fight Tory austerity plans before he died. He argued that in today’s Britain, access to disability-related supports and services is being stripped away.

Hawking was a complex, brilliant, well-supported, disabled man who did more than increase our understanding of the universe. He fought to increase our understanding of disability, and the social forces that create barriers to people that have them. To honor his legacy, we can't just look to the stars: We must create more possibilities for people like him here on earth.

David Perry is a freelance journalist and historian. He covers politics, disability, higher education and history.