The highest criminal justice priority of the current Supreme Court majority is apparently to make the state’s machinery of death work as efficiently as possible — and if this means some major rights violations along the way, they seemed to say on Monday, so be it. That was made evident when a bare majority of the court held that the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment” does not forbid the state of Missouri from executing a prisoner in a way that would effectively torture him to death.

If that outcome seems perverse to you, you’re right. But the Roberts Court is committed to allowing states to execute people in any barbaric manner, no matter how difficult such executions are to square with the text of the Constitution.

The current issue is thus: The state of Missouri has had to adjust its lethal injection protocols because drug suppliers are increasingly unwilling — as is their prerogative — to participate in a practice that is considered contrary to basic principles of human rights by most democratic nations.

Missouri’s proposed solution to the lack of availability of its preferred execution drugs is a method of lethal injection would be particularly cruel to Russell Bucklew, who was convicted of murder and other crimes 22 years ago. As Justice Breyer described it in his dissent, Bucklew presented evidence that “executing him by lethal injection will cause the tumors that grow in his throat to rupture during his execution, causing him to sputter, choke and suffocate on his own blood for up to several minutes before he dies.”

Bucklew, then, was not arguing that the death penalty is categorically unconstitutional, or even that the method of lethal injection used by Missouri was always unconstitutional, but that the method applied in his particular case would be “cruel and unusual” because of his particular medical condition.

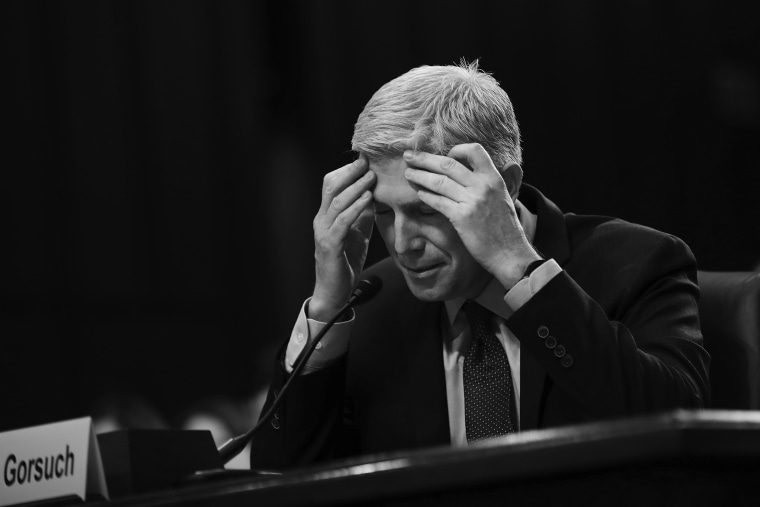

The majority opinion, written by Trump nominee Neil Gorsuch and joined by the other four Republican nominees, nonetheless dismissed Bucklew’s argument. According to Gorsuch, “the Eighth Amendment does not guarantee a prisoner a painless death — something that, of course, isn’t guaranteed to many people, including most victims of capital crimes.” Inflicting even excruciating pain on a prisoner in the course of executing him, therefore, does not necessarily violate the Eighth Amendment in the view of the Roberts Court.

Based on the majority’s textualist reading of the Eighth Amendment, a method of execution is unconstitutional only if a form of punishment is a “long disused” one that represents a “superaddition” of “terror, pain or disgrace.” Because lethal injection has been the dominant form of execution in the United States for decades, as states mostly abandoned the more visibly brutal methods of hangings, firing squads, electric chairs and gas chambers, the disuse condition makes challenges to lethal injection almost impossible to win no matter what the consequences — which of course it the point.

Gorsuch’s opinion also extends a very weak argument made by Justice Alito in Glossip v. Gross in 2015. Because of Glossip, even if a petitioner could show that a method of execution would inflict excruciating pain, the execution was constitutional unless the condemned prisoner could identify a less painful method available to the state. Gorsuch applied that standard to this case, arguing that Bucklew was required to demonstrate “a feasible and readily implemented alternative method of execution the state refused to adopt without a legitimate reason.”

Because of the availability of drugs commonly used in lethal objection has become heavily restricted by the manufacturers (a function of, you know, capitalism), this effectively sets up a Catch-22 for defendants: Legal representatives must imagine alternative forms of putting their clients to death and show that they are feasible and available but the state refused to adopt them. In other words, it puts the onus on criminal defense lawyers, many of whom are dedicated to limiting the application of the death penalty, to find alternative methods of execution for the state to adopt against their clients.

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor previously argued in her Glossip dissent, this argument makes very little sense. The fact that people’s moral revulsion to the death penalty makes certain forms of execution impossible for the state to carry out doesn’t render an otherwise unconstitutional execution constitutional. “A method of execution that is “barbarous,” or “involve[s] torture or a lingering death,” does not become less barbarous or torturous s just because it is the only method currently available .

Even assuming, for the sake of argument, that the Constitution does not categorically forbid capital punishment as cruel and unusual punishment, it doesn’t follow from this that the state must be able to carry out clearly torturous executions because it does not have a readily available alternative to its preferred cruel method.

Nor should it be the job of condemned prisoners to identify alternative methods of execution. As Breyer puts it in his dissent, “Even in the unlikely event that the state could not identify a permissible alternative in a particular case, it would be perverse to treat that as a reason to execute a prisoner by the method he has shown to involve excessive suffering.”

Gorusch’s aside about how “victims of capital crimes” generally do not have a “painless death” is telling, however. While his opinion uses historical factoids and dictionary definitions to dress up its predetermined conclusion, Gorsuch is unable to hide that he’s a soldier in a culture war, not a dispassionate judge reluctantly applying the law. His opinion is filled with palpable contempt for legal challenges brought by death penalty defendants and frustration for the fact that states can’t execute people more quickly.

The same contempt can also be readily seen in the recent refusal of the same five justices in today’s majority to stop a different execution, although the state’s refusal in that case to allow a condemned Muslim prisoner to have his imam be present is in flagrant violation of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.

But compassion for crime victims should not overwhelm the precepts on which the country was founded, and making sure the machinery of execution is well-oiled by the courts is the wrong priority. As Justice Sotomayor observes in her dissent in Monday’s case, “[t]here are higher values than ensuring that executions run on time.” Ensuring that people are not tortured to death are certainly among those higher values, and had the Electoral College not selected the runner-up in the 2016 popular vote, the Supreme Court would actually have represented them again.