Joe Biden’s history of personal tragedy is woven into his presidential candidacy, especially when it comes to cancer. Biden’s grief when speaking to crowds about his son Beau, who passed away from brain cancer, touches voters. He asks his audiences if they or their relatives have been diagnosed with cancer. Most recently, Biden’s campaign press secretary, TJ Ducklo, was diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer.

On the campaign trail, Biden has even talked of trying to cure cancer, a disease that has vexed presidents ever since President Richard Nixon declared war against it in the 1970s. President Donald Trump, too, has vowed to cure cancer if reelected president.

On the campaign trail, Biden has even vowed to try to cure cancer, a disease that has vexed presidents ever since President Richard Nixon declared war against it in the 1970s.

But it is difficult to discuss a complex malady like cancer in the language traditionally reserved for other illnesses. No silver bullet is likely to exist, as cancer is not one disease but hundreds of distinct diseases with distinct causes, gene mutations and vulnerabilities. Progress on each form has thus varied, with some types more responsive than others despite a recent proliferation of new treatments.

While political rhetoric and metaphor may help fill the coffers of cancer research, therapies of significant consequence are likely to be found in decades and not by the end of the 2024 presidential term. And until the gap narrows between America’s hopes and our overall cancer science, we need to focus on the places where a sizable dent can be appreciably made now: prevention and greater health care access.

By the late 1940s, postwar America was changing in unprecedented ways. A synergy of miracle drugs like antibiotics, public health and hygiene had rescued society from the scourge of diseases and infection. New hospitals were rapidly opening, life spans were increasing and medical cures were becoming an expectation.

But cancer proved far more challenging.

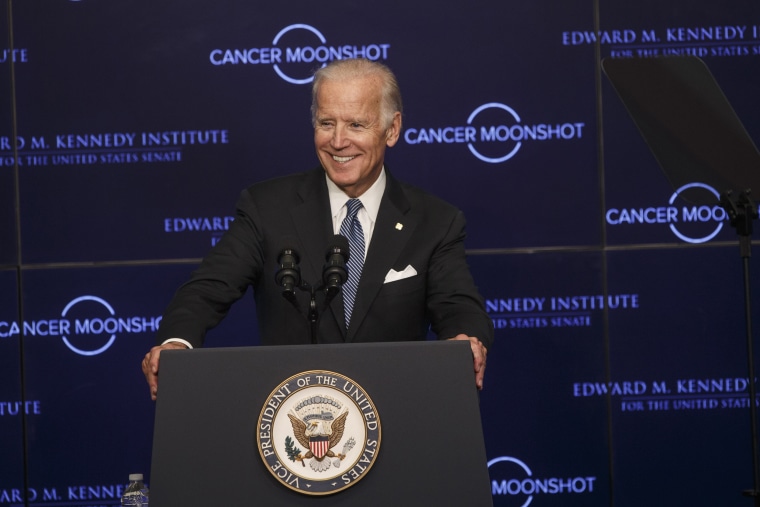

The knotty issue has since found its way into the Oval Office. Nixon entered the fray when he announced his war in 1971. Forty-five years later, President Barack Obama spoke of the need for a “moonshot” to end cancer. But despite the sizable reach of these nationally coordinated efforts, a cure continues to elude our grasp.

Every patient’s cancer is different because each cancer genome is different. Not only is breast cancer unique from prostate cancer, but one person’s leukemia can differ from someone else’s.

As oncologist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Siddhartha Mukherjee notes in his book “The Emperor of All Maladies,” most tumors are a “genetic bedlam” with “mutations piled upon mutations upon mutations.” The most consequential of these mutations, known as “driver” mutations, play a pivotal role in the biology of a cancer cell.

Because many tumors harbor a multitude of these driver mutations, molecular therapy that targets only one mutation may slow a metastatic cancer but it is unlikely to cure it. As Ravi Parikh, an oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania, observed for Vox in 2017, this approach inevitably falters because you are trying to “defeat an army of enemies by picking off individual soldiers one at a time.”

Similarly, immunotherapy, which harnesses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer, may only temporarily halt dynamic cancer cells before they become resistant to its effects. It’s important to note that even prior to the development of resistance, immunotherapy was only effective in 15 to 25 percent of patients.

Even patients whose cancers are in remission after being diagnosed at early stages rarely hear the word “cure” from their oncologists. A 2013 study in the Journal of Oncology Practice found that 81 percent of oncologists hesitated to use the word “cure” in front of patients and 63 percent never used the term. This is because residual cancer cells may remain years after treatment, genetic or environmental risk factors may persist or cellular damage from previously administered chemotherapy or radiation may lead to new cancers.

The researchers who are being tasked to assimilate these many gene mutations and cancer pathways in order to develop impactful drugs have a torturous journey of decades ahead of them. As Lev Facher and Andrew Joseph of STAT rightly note, “Discoveries cannot be predicted, research is rarely linear, and scientists often require false starts before they learn how to overcome particular roadblocks in research.”

The byzantine complexity of cancer biology likely precludes a single panacea for all forms of cancer.

The byzantine complexity of cancer biology likely precludes a single panacea for all forms of cancer. A more hopeful scenario has many cancers being reduced to a chronic disease in the vein of diabetes or hypertension, where a daily pill targeting a potent, far-reaching cancer pathway can keep things controlled for years. This was most notably achieved with the development of Gleevec (imatinib) for chronic myelogenous leukemia.

But there are opportunities already lying in plain sight to save lives that do not rely on the uncertain promise of new cancer drugs. Though no active moonshot funds have been allocated here, optimized prevention strategies (smoking cessation, weight loss, improved diet, etc.) and early detection (colonoscopy and mammography) can result in a 33.5 percent drop in cancer deaths by 2035.

In addition, improved health care access will ensure that today’s formidable armamentarium of drugs and cancer screening modalities are available to everyone. And this is why it matters how politicians discuss cancer. For example, the 2020 campaign trail provides opportunity to talk about how research shows Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act may be able to decrease racial disparities in cancer treatment.

Siddhartha Mukherjee concludes in his book that “Cancer is not a concentration camp, but it shares the quality of annihilation.” For a disease so potentially crippling, we need less campaign hyperbole and more policies that can be effective now.