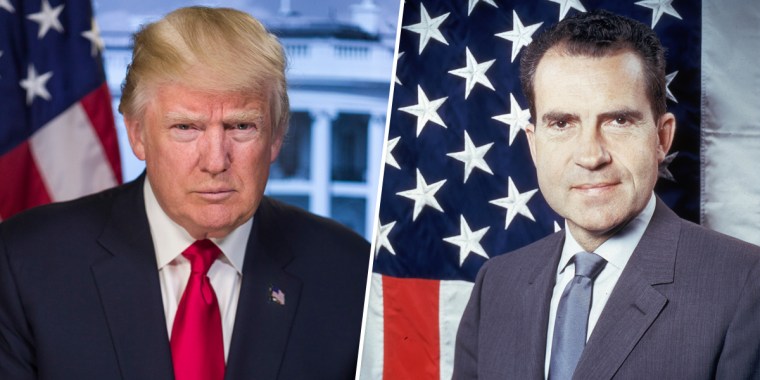

When President Richard Nixon resigned in August 1974, his successor, Gerald Ford, told the nation that “our long national nightmare is over.” But with Alan Dershowitz’s arguments during President Donald Trump's impeachment trial on Wednesday that a president can do almost anything “that he believes will help him get elected — in the public interest,” it is clear that Nixon’s resignation left a serious gap in the precedents of impeachments.

Indeed, Dershowitz may have some of the last words on the matter. On Friday, the Senate voted to not allow new witnesses, including John Bolton. It seems increasingly likely that the Senate will vote soon to acquit Trump. So what went wrong here, if you believed conviction was appropriate? The answer starts with the Nixon precedent, or better said, the lack of precedent.

On Friday, the Senate voted to not allow new witnesses, including John Bolton. Indeed, it seems increasingly likely that the Senate will vote soon to acquit Trump.

The precedents set by each impeachment are important. And what happened to Nixon can help explain what happened, however different, to Trump.

The nation has only faced an official impeachment vote three times: President Andrew Johnson in 1868; President Bill Clinton in 1999; and now President Donald Trump. It is often incorrectly assumed that Nixon was impeached but resigned before the Senate could convict. Instead, the House Judiciary Committee sent the articles of impeachment to the full House, but the body never got the chance to vote on them. An intervening event, the Supreme Court order that Nixon turn over his tapes, started a chain reaction that led quickly to Nixon’s resignation on August 9, 1974.

Nixon’s action, while saving the nation further agony in the short run, may be responsible for this trial’s mangling of the constitutional standards for impeachment. Trump’s lawyers have contended that “high crimes and misdemeanors” requires the showing of the commission of a crime. Dershowitz, contrary to his own statements during the Clinton impeachment, vehemently argued that a president cannot be impeached for “abuse of power” unless a crime in involved.

Had Nixon fought his impeachment there may have been some clarity on these questions. The House Judiciary Committee voted in favor of three articles: one on the cover-up of the Watergate investigation; a second on abusing the powers of his office; and a third on his willful disobedience of Congressional subpoenas.

The exact same arguments we see today broke out in 1974, also along party lines. The Democratic majority in the committee argued that a technical showing of the commission of a crime was not required. The question, rather, was what the English practice had been focused on: abuse of power. “The emphasis,” they wrote, “has been on the significant effects of the conduct—undermining the integrity of the office, disregard of constitutional duties and oath of office, arrogation of power, abuse of the governmental process, adverse impact on the system of government.”

The Republicans in the minority, on the other hand, insisted that impeachments “can lie only for serious criminal offenses.” The Republicans could find no provable crime with Nixon, even though they had John Dean’s testimony and transcripts of tapes that disclosed Nixon agreeing to the payment of “hush money” to criminal defendants to keep them from talking, to say nothing of dangling pardons for at least E. Howard Hunt. The Republicans quibbled about whether Nixon was really authorizing the payments or if there was enough proof of his misuse of the pardon power.

Had Nixon’s impeachment reached fruition in the Senate, a precedent would have been set, almost certainly establishing the majority view that impeachment is all about abuse of power.

But the Supreme Court intervened. In late July 1974, the court decided United States v. Nixon and ordered the president to turn over certain tapes. One tape of a conversation between Nixon and his chief of staff on June 23, 1972, hit hard. In the conversation, Nixon agrees that the CIA should tell the FBI to end the Watergate investigation on the bogus premise that the FBI might be getting into CIA operations.

Virtually overnight, the Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee announced that Nixon had “admitted” a crime in this “smoking gun” tape and they would join the Democrats, who had already voted out the articles of impeachment. Nixon’s support in the Senate evaporated and Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., among others, visited Nixon to tell him the gig was up.

What is highly ironic about this scenario is that if lawyers had carefully analyzed the smoking gun tape at the time, they would have noticed that one critical element of the crime of obstruction of justice was missing: No grand jury had been empaneled by June 23, 1972. Those who have studied the Mueller report will know that the crime of obstruction requires an obstructive act, a nexus between the act and an official proceeding and corrupt intent. Nixon could not be obstructing a grand jury investigation of Watergate if it did not yet exist.

This is why it was so unfortunate for history that Nixon didn’t face impeachment and a full trial in the Senate.

Thus, technically, there was no crime in that conversation. But, really, is there any doubt that when a president orders a government agency to shut down an investigation into criminal activity of his reelection campaign that that constitutes impeachable conduct? Is it not a classic abuse of power?

Dershowitz might disagree. But this is why it was so unfortunate for history that Nixon didn’t face impeachment and a full trial in the Senate: Abuse of power as a reason for impeachment would have been put on the precedential map.

The script has instead been flipped. In the famous David Frost interviews of Nixon, Nixon said, “When the president does it, that means it is not illegal.” In the movie version, “Frost/Nixon,” this is the dramatic moment in the film when David Frost finally breaks through and gets the better of Nixon. Today it would be a tagline for Trump’s presidency.

It is likewise unfortunate that President Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon before he could stand trial for the cover-up crimes as a co-conspirator (he was an unindicted co-conspirator at the time of Ford’s pardon). Another important precedent would have been established — that after leaving office, a president, as any other citizen, should face criminal charges and criminal consequences if warranted. The Constitution expressly reserves criminal punishment for one impeached after an impeached officer is removed from office.

So, the question now is: Are we just starting our long national nightmare?

Related: