President Donald Trump ignored the professional advice of his senior uniformed military leadership as well as Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and intervened in war crimes cases involving three U.S. service members — Lt. Clint Lorance (U.S. Army), Maj. Matthew Golsteyn (U.S. Army Special Forces), and Chief Edward Gallagher (Navy SEAL). On Friday, Trump issued pardons for Lorance and Golsteyn and restored the rank Gallagher had lost based upon his court-martial in July (Gallagher was acquitted of murder but found guilty on one minor charge related to taking a picture with the dead body of an ISIS fighter in Afghanistan).

The Pentagon leadership as well as numerous senior retired military officers strongly opposed this action. They firmly believed such pardons could undermine the military justice system.

The Pentagon leadership as well as numerous senior retired military officers strongly opposed this action. They firmly believed such pardons could undermine the military justice system and run contrary to long-term American national security interests. Retired Gen. Chuck Krulak, former commandant of the Marine Corps, characterized the president’s decision as betraying the ideals of the American military profession and further objected that it “undermines decades of precedent in American military justice that has contributed to making our country’s fighting forces the envy of the world.” Similar comments were made by retired Gen. Marty Dempsey, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

As a combat veteran, former dean of the U.S. Army War College, as well as a former faculty member at two service academies, I must wholeheartedly agree with these two distinguished officers.

There is no doubt that Trump has the legal authority as both the president and the commander in chief of the armed forces to make this decision, just as he was legally within his rights to pardon controversial former Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio or conservative provocateur Dinesh D'Souza. But legal authorities quickly noted that presidential intervention in murder cases is unprecedented. For example, Lt. William Calley, who was convicted in 1971 of murdering 22 unarmed civilians during the Vietnam War, was paroled by the secretary of the Army in 1974 (rather than pardoned) after pressure from President Richard Nixon. (Nixon resigned a few months before Calley's parole became official.)

Every one of these cases was different. Lorance was convicted of second-degree murder in 2013 after ordering his men to fire on three Afghan motorcyclists. Members of his own platoon testified at the trial that the Afghans posed no threat. It was further proven that Lorance falsified reports in an attempt to cover up the attack. Lorance’s conviction was reviewed and confirmed by the Court of Military Appeals due to the nature of the charges.

Golsteyn’s pardon ends a decadelong process following the killing of a suspected Afghan bombmaker in 2010. At the time of the murder, it was unclear whether enough evidence existed to charge Golsteyn. But in 2015, he admitted to the killing in a CIA job application and publicly reiterated his guilt on Fox News in 2016. His court-martial was scheduled to begin in February, so it was particularly unusual for the president to pardon him prior to trial — where his guilt or innocence would be determined.

Furthermore, the president had previously suggested he might intervene in this case, leading to concerns of inappropriate command influence that would have likely complicated the legal process.

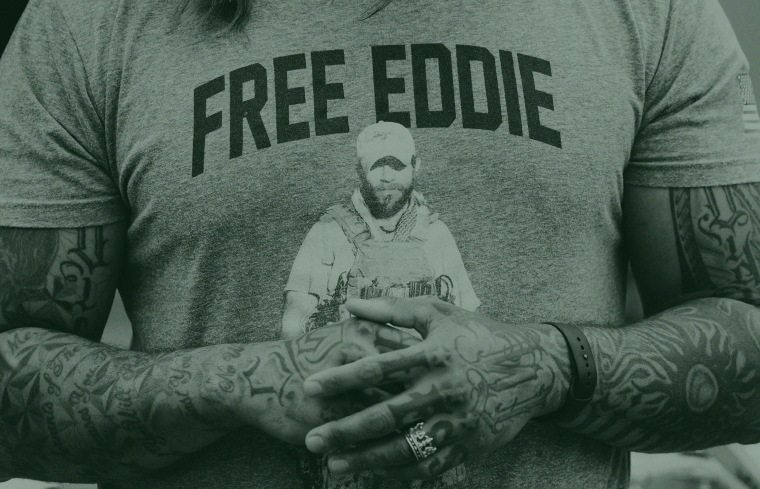

Navy Special Warfare Operator Chief Gallagher had been charged in 2017 with stabbing to death a young ISIS prisoner, indiscriminately shooting Iraqi civilians, threatening a fellow SEAL in order to cover up these incidents and posing for photographs while standing over a dead ISIS fighter. Members of his SEAL team had demanded an investigation and several testified against him. But Gallagher’s court-martial was fraught with numerous problems including allegations of inappropriate actions by the prosecution, and a key witness also changed his testimony during the trial. As a result, he was exonerated on all but the last charge. His sentence, which included a fine and reduction in rank, was reviewed and upheld by Adm. Michael Gilday, chief of Naval Operations.

Several times the president described the treatment of these service members as “unfair” even though a thorough Article 32 investigation, comparable to a civil grand jury trial, had been conducted to establish probable cause. Furthermore, the court-martial members in each case were officers or peers of the accused. All were also combat veterans who fully understood the so-called “fog of war” and the need for quick decision during urgent and dangerous situations.

Trump’s justifications for the pardons sadly suggest the commander in chief lacks an in-depth understanding of the military, its culture, and professional ethic. On the day of the announcement, he suggested in a White House statement that he wanted to give soldiers “the confidence to fight” for their country. He previously argued on Twitter, “We train our boys to be killing machines, then prosecute them when they kill!” But service members are thoroughly trained, well-led and confident. They are also taught from the beginning of their service that they are legally bound to follow the Military Code of Conduct and laws of land warfare.

Article VI of the code acknowledges their individual responsibility: “I will never forget that I am an American, fighting for freedom, responsible for my actions, and dedicated to the principles which made my country free.” These rules are based on principles of distinction, proportional response, targeting, military necessity and the avoidance of unnecessary suffering. All service personnel are briefed on rules of engagement derived from these legal principles before and during deployments. These are the foundation of the military’s professional ethic and an integral part of military training and education. They are taught to enlisted members, noncommissioned officers and officers to provide each the capacity to distinguish right from wrong in combat.

Ultimately, the American military is a professional force designed to employ the measured and disciplined application of force in behalf of the nation. It is not a “killing machine.” The president should understand that military ethics is what separates a disciplined force from an armed mob. Arizona Sen. John McCain, a longtime critic of the president, had clearly articulated this sentiment. McCain did not “mourn any terrorist’s death” but rather what the nation lost when “we confuse or encourage those who fight this war for us to forget that best sense of ourselves.” The senator firmly believed that throughout the horrors of war, “we are always Americans, and different, stronger and better than those who would destroy us.”

Unfortunately, the president’s decision will likely have further deleterious effects for the military justice system as well as national security. First, military commanders at all levels may be concerned about being second guessed for decisions they make about holding their troops accountable for potential war crimes. In the future, they may even hesitate to do so. Second, some service members may be encouraged to believe that in all cases the ends justify the means. This may result in future violations of international law and further alienate those we are supposed to be supporting. Third, what message does the president’s decision send to the members of Lorance’s platoon or Gallagher’s SEAL team? They believed their leaders had violated the professional ethic and, as a result, insisted they be held accountable.

The president should understand that military ethics is what separates a disciplined force from an armed mob.

Finally, the United States currently has over 170,000 troops deployed in nearly 150 countries around the globe. In most of these nations, the American military is afforded special legal status that precludes them from being subject to local courts. Foreign leaders accept these agreements based on a belief that the American military has historically held its service members accountable according to a very strict code of justice. Some legal experts now worry that these nations could believe in future that the United States will no longer hold its troops responsible for crimes they commit against their citizens.

A charitable explanation of the president’s decision might suggest he simply failed to understand the gravity of his actions. He may have also had the misguided belief it would enhance his standing with the military. This relationship has recently been strained by Trump’s precipitous decision to abandon the Syrian Kurds, to the dismay of not only senior U.S. military leaders but also individual soldiers who had served in Syria.

Others might point to political motivations. Trump may believe the pardons will be well received by his political base. The announcement was delivered at a moment the president may have wished to shift attention away from the ongoing impeachment inquiry. Furthermore, it occurred the same day that Roger Stone, a longtime friend and political adviser to the president, was found guilty for lying to Congress in a case involving the 2016 Trump campaign and Stone’s efforts to release stolen Democratic Party emails through WikiLeaks.

Whatever the president’s reasoning, he would be well served to consider the future impact of this decision. In doing so, he would benefit from listening to the views of a young officer — “that is not who we are.”