For a woman who barely topped 5 feet tall, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a towering figure. As news of her death circulated Friday, tributes poured in from around the world. She will be remembered as a lot of things, some of them human, some seeming to defy mortality. She's an icon — the Notorious RBG, her face printed on T-shirts and mugs and birthday cards and, in our weird Covid-19 world, masks. She was a feminist trailblazer and one of America's greatest legal scholars, from her time as Columbia Law's first tenured female professor to co-founding a novel women's rights project at the ACLU to litigating cases in the Supreme Court to finally sitting on the court itself.

And she was also a person, just skin and bones: a beloved wife, an adoring mother, a proud grandmother, an opera lover, an adventurer, a good friend and a woman who hit the gym several times a week well into her 80s. We all knew she was human. But somehow, she seemed invincible.

For a woman who barely topped 5 feet tall, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a towering figure.

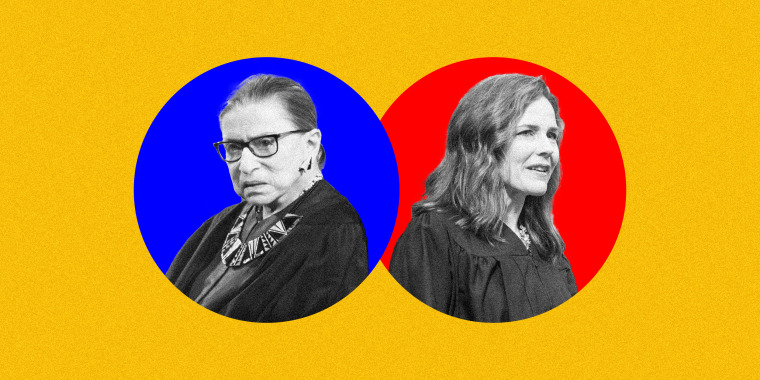

President Donald Trump and Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell are already pushing to fill her vacant seat with a conservative before the election. Trump is promising he will nominate a woman, with Amy Coney Barrett, a federal appellate court judge who has spoken out against abortion and seriously concerns LGBTQ advocates, emerging as one of the front-runners.

Ironically, although Barrett opposes many of the things Ginsburg spent her life fighting for, she owes her own career — and her potential seat on the Supreme Court — to Ginsburg herself and other pioneering women like her.

Ginsburg was a legal force and a cultural one. Before she was the Notorious RBG, she was a rare female lawyer in an overwhelmingly male profession. She could have played nice with the boys; instead, she fought for women. In doing so, she indelibly and often invisibly shaped the lives of the women who would grow up to wear her face on their clothing, share her image on Instagram and pen books celebrating her contributions — and also the women who would use their own access to power and influence to pull the ladder up behind them, making life harder for others.

When Ruth Bader Ginsburg entered Harvard Law School in 1956, she was one of just nine women in a class of about 500 men. She transferred to Columbia and graduated at the top of her class, but many judges wouldn't hire a woman as a clerk. When she began to teach law, there were fewer than two dozen female law professors.

Want more articles like this? Follow THINK on Instagram to get updates on the week's most important cultural analysis

Sixteen years after Ginsburg started at Harvard Law, Barrett was born. The same year, 1972, Notre Dame Law School — which would become Barrett's alma mater — began admitting female students, thanks to people like Ginsburg who pushed through doors long closed. Barrett wasn't even 1 year old in 1973, when the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade and legalized abortion nationwide; just a few years before that, the court had decided Griswold v. Connecticut, which established a right to sexual and intimate privacy and legalized contraception. With those two decisions, women had unprecedented power to control their reproductive lives, which in turn gave them greater control over their educations, their finances and their futures. In Roe and Griswold's wake, women flooded into college, law school and the workplace. Barrett was one of them.

But instead of doing what Ginsburg did — pushing doors open, reaching out to help others through — Barrett tried to slam them shut. She went on to be a conservative lawyer, professor and judge, and if she is appointed to the Supreme Court, she will likely be key in undermining much of what has allowed American women to make the progress they have: abortion rights, contraception access and prohibitions on many forms of gender discrimination.

This certainly puts Barrett at odds with most of America's most venerated female lawyers and jurists and with female lawyers more generally. Feminism creates something like a virtuous cycle: As women gain greater opportunity, they become more invested in preserving and expanding what they've gained. But making the initial gains, and moving them forward, has always been difficult. Constraints on women's rights in the United States have historically been couched in the language of benevolence and protection, of women being too moral and too delicate to play in the same arena as men. Gender discrimination was justified as chivalrous, as an effort to protect women and treat them as ladies. This, Ginsburg noted, "helps to keep women not on a pedestal, but in a cage."

She fought to break that cage open by, cannily, taking on a case in which the victim of gender discrimination was a man. From there, others flowed, and the wall of laws and rules enshrining disparate treatment of the sexes began to come down, brick by brick. Ginsburg did much of the dismantling with her own hands, but she was part of a long history and a larger trajectory. She was always clear that she wasn't the first woman using the courts to fight for women, nor the only one; she certainly knew she wouldn't be the last. But her work fundamentally reshaped the way we understand sex discrimination — as an inequity, not an act of benevolence — and how the courts address it. Thanks to Ginsburg, any law that discriminates on the basis of sex has to have a damn good reason (or, to put it in legalese, a law that discriminates on the basis of sex must further an important government purpose, and it must do so in a way that is substantially related to that purpose).

Thanks to Ginsburg and the many women like her — most of whom didn't ascend to the highest court in the land but still made enormous contributions to women's rights and the American legal landscape — by the time I went to law school, my class was 50 percent female. Female professors were no longer novelties. Gender disparities remain, but the progress in one woman's lifetime has been enormous.

And importantly, by the time Ginsburg gained a mass pop culture following, several generations of women had surged into the workforce and carved out a little more space and a little more opportunity. There is still much to be gained — gender pay and hiring gaps persist; women often find themselves pushed out of work when they have children; women are radically underrepresented at the top tiers of nearly every industry and radically overrepresented in the essential but low-status, low-wage care work that keeps our economy churning.

But those of us who sip our morning coffee from a mug with RBG's face on it can look around at a better, fairer nation for women than the one she was born into. If we pause, many of us can realize that so many of the doors we walked through — that perhaps we didn't even notice had once been shut — had been kicked down by women who went first, Ginsburg among them.

Most women whose life trajectories and opportunities were imperceptibly shaped by Ginsburg’s hand have no idea.

Ginsburg is a rare public figure and trailblazer whose accomplishments were realized and lauded while she was still alive (consider, for example, that Susan B. Anthony didn't live to see women get the vote and that journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who died in 1931, didn't get an obituary published in The New York Times until 2018 and was finally awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 2020). Many of the same women who benefited from Ginsburg's work were able to thank her, or at least admire her.

Perhaps more important, though, is the fact that most women whose life trajectories and opportunities were imperceptibly shaped by Ginsburg's hand have no idea. For most American women under the age of 40, the society we grew up in — one in which women worked outside the home in every field, where pay discrimination wasn't yet eradicated but was at least both decreasing and widely condemned, where planning the number and spacing of your children was the norm and where much more was expected of men in the home and women outside of it — wasn't novel but normal.

I didn't know RBG, but I imagine this tectonic shift in women's basic assumptions about their lives must have been one of her greatest accomplishments: not being lionized or thanked for what should have always been, but seeing what she dreamed of, was told was impossible and did anyway become so basic that we forget things were ever any other way.

That's why it would be such an insult to Ginsburg's life and her work to appoint a judge like Barrett: someone who is happy to take advantage of the opportunities her predecessors created, who is smart enough to grasp how she got where she did and is nonetheless reactionary enough to help burn RBG's legacy to the ground — and make it that much harder for other women to rise.

Related: