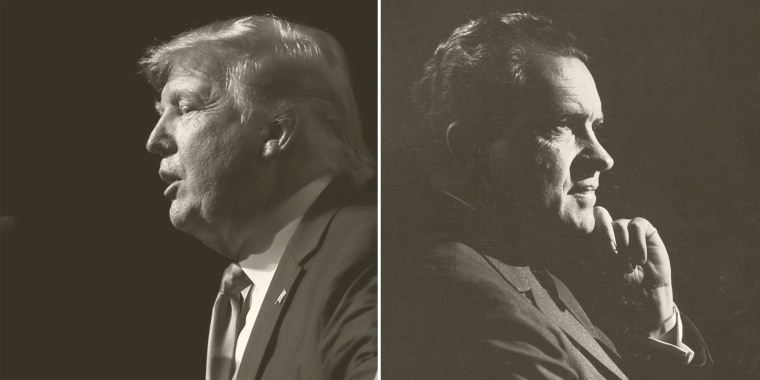

Poor Richard. When we think of President Richard M. Nixon during Watergate, many people picture an irrational and pitiable figure — drinking too much, wandering the halls of the White House, talking to the paintings on the walls, trapped in a crisis created by his crazed resentments.

That isn’t the whole of it, though. This was a man who, by the time of Watergate, had been in national public life for more than 30 years. He had served as a congressman, a senator and then vice president for President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Nixon was a skilled lawyer who had argued before the U.S. Supreme Court and survived political crises both public and personal. He knew the powers and limitations of each piece of the U.S. government — including his own.

Nixon was a skilled lawyer who knew the powers and limitations of each piece of the U.S. government — including his own.

Toward Watergate’s end, Nixon took stock of his situation in light of his deep experience and educated judgment — and, in a farsighted move, resigned the presidency before the U.S. House of Representatives could impeach him. Nixon, in other words, knew when the jig was up.

Today, it’s Donald Trump who’s enmeshed in a presidential scandal. It’s hard to imagine a man whose political experience and temperament are less like Nixon’s. Nixon had a lifetime in politics; Trump never held a political office before the presidency. Nixon, at least in public, spoke and wrote in the measured tones of an accomplished government official; Trump — well, we know how Trump expresses himself. Nixon was a subtle strategic thinker; Trump’s signature skill, as his wife Melania has said, is to "punch back 10 times harder."

In one key way, however, the difference in character gives Trump a far better chance of surviving as president: Trump will do almost anything to avoid acknowledging that he’s been defeated. He never accepts it — even when it happens.

Yet, Trump has weaknesses of his own — and he’s begun to reveal them. They give us a clue about what kind of setbacks may actually persuade him to accept that the jig is up.

For two years, from the June, 1972 Watergate break-in all the way to the summer of 1974, it looked as if Nixon just might make it through his scandal. True, the 1973 Saturday Night Massacre was bad. But even then, the end wasn’t certain.

The previous May, Nixon’s attorney general, Elliot Richardson, had appointed former Solicitor General Archibald Cox as Watergate special prosecutor. In October, when Cox tried to subpoena tapes that Nixon had made of Oval Office conversations, the president determined to fire him. But it took Nixon three tries and two resignations — first of Richardson, then of Richardson’s deputy attorney general, William Ruckelshaus — to find an official who would fire Cox. The public reaction to the firing was explosive.

Even with all that, Nixon still had a fighting chance. The only testimony that tied Nixon directly to the Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up came from former White House Counsel John Dean, whom some considered a less-than-savory character. If it came to a credibility contest between the two men, Nixon believed he would win.

After all, there was no “smoking gun:” no written record or piece of testimony in which Nixon himself could be seen or heard directing the cover-up.

There was no smoking gun — until there was. The tape confirming that Nixon had tried to use the Central Intelligence Agency to shut down any further F.B.I. investigation of the Watergate break-in finally surfaced after repeated attacks on the White House rock face by the chisels of investigators and litigators.

Once that tape became public, three senior Republican officials — Sen. Barry M. Goldwater, Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott and House Minority Leader John Rhodes — visited Nixon in the White House and updated him about his dwindling support on the Hill.

Some versions of the story say the Republican lawmakers told Nixon to resign. In other accounts, however, the congressmen did not make any such recommendation. They didn’t have to. Nixon, a canny political analyst and vote-counter nonpareil, foresaw that all his reasonably possible future moves were doomed to end in checkmate. He knew the jig was up.

You might think that Trump, when viewing the evidence that’s been gathered so far, would also conclude that the jig is up this time. The public testimony by multiple witnesses has been damaging. In addition, this evidence is now growing tentacles. The House Intelligence Committee has subpoenaed phone logs, featuring players like Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani and the committee’s ranking member, Rep. Devin Nunes, R-Calif., that virtually beg journalists to mine them for additional leads. Indictments by the Southern District of New York have already dredged up at least one cooperating witness, and the investigation continues.

Moreover, once the articles of impeachment hit the Senate, even one controlled by Republicans, witnesses who declined to testify to the House may find themselves spilling the beans to Chief Justice John Roberts, who would preside over the trial. It will be a new ball game with fresh and uncontrollable hazards.

Trump has the protection of a highly polarized public and the steadfast congressional Republicans who reflect it. The archetype of House Republican behavior during the Intelligence Committee hearings on impeachment, for example, was Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio: “What you heard,” he said to Ambassador William Taylor, who testified about the hold-up of Ukraine aid, “did not happen. It’s not just could it have been wrong, the fact is it was wrong, because it did not happen.”

But the Republicans aren’t Trump’s chief asset. His biggest defense, for better or worse, is that he doesn’t have the temperamental or intellectual capacity to conclude that the jig is up. As a result, the jig may not be up for him at all.

Trump is known for not just saying things that aren’t true, but for betraying no visible embarrassment when he’s brought face-to-face with the discrepancies. So when Trump fights accusers who want to bring him down, his strength — composed in equal parts of his sense of grievance and his belief in his own persuasive powers — is unburdened by shame or embarrassment at his past words and actions.

Trump isn’t a strategist or vote-counter; he’s a counterpuncher. For as long as you keep hitting him, he’ll just keep hitting back. You can’t persuade him that the jig is up — at least not by hitting him directly.

Trump is known for not just saying things that aren’t true but betraying no visible embarrassment when he’s brought face-to-face with the discrepancies.

But Trump does have another kind of weakness. At the recent North American Treaty Organization’s 70th anniversary birthday meeting in London, an open microphone picked up allied leaders — French President Emmanuel Macron, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the Netherlands’ Prime Minister Mark Rutte and Britain’s Princess Anne — allegedly mocking Trump. The video showed the group’s members smiling and animated. They were in high spirits.

The next day, Trump’s reaction was far from coherent. He called Trudeau two-faced. He explained Trudeau’s comment as a reaction to Trump’s demand that Canada pay its required 2 percent of gross domestic product to the alliance. But he also called Trudeau a “nice guy” and later described the “two-faced” comment as “funny.” He then canceled his participation in the closing press briefing and left the NATO meeting early.

Trump’s flailing recalls his 2018 speech to the U.N. General Assembly, in which he asserted that his administration had accomplished “more than almost any administration in the history of our country.” The assembled diplomats laughed at him. Trump’s response from the podium was, “So true.” Then, he said to the delegates, “Didn’t expect that reaction, but that’s OK.’ Afterward, he claimed that the delegates hadn’t been laughing at him but with him. Delegates confirmed that, no, they had definitely been laughing at him.

In short, Trump is not ready for this kind of attack. He’ll keep on counter-punching for as long as he gets punched, but he doesn’t show the same kind of spirit when he’s subjected to mockery — at least mockery by people he considers his peers.

That may be a clue as to what it will take to persuade Trump, as opposed to Nixon, that the jig is indeed up. It may be a roadmap for his opponents as well: less expression of nonstop outrage, more demonstration of why he’s become a laughingstock.