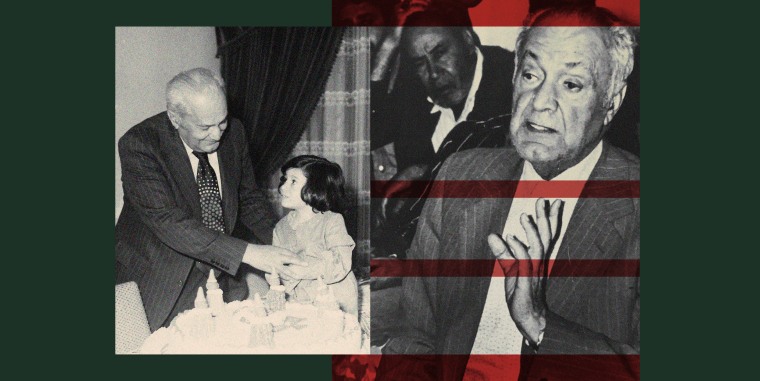

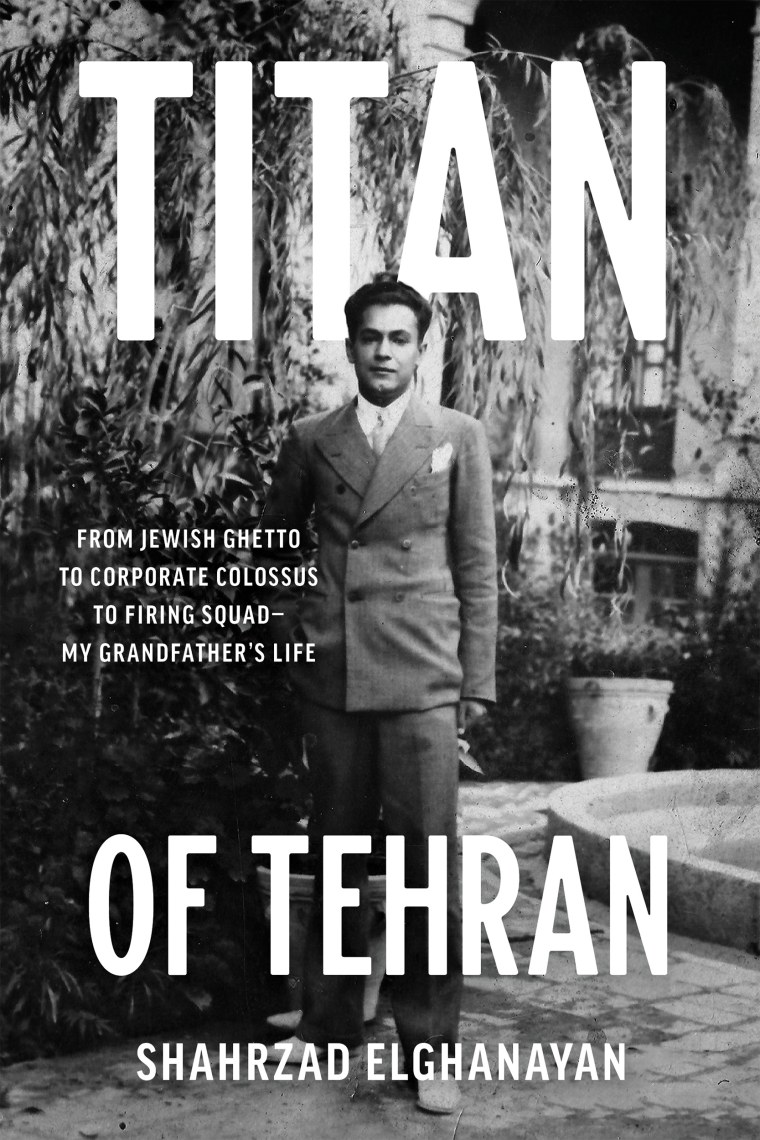

This excerpt is adapted from “Titan of Tehran: From Jewish Ghetto to Corporate Colossus to Firing Squad — My Grandfather’s Life,” a book by Shahrzad Elghanayan, senior photo editor for NBC News Digital. The book, which was published in November by AP Books, tells the story of Habib Elghanian, a Jewish industrialist and longtime community leader in Tehran, Iran, who was killed during the first round of civilian executions of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. The book explains the decline of Iran’s once-thriving Jewish community and offers insights into the first months of U.S. relations with the new Islamic Republic.

“Sorry, sir, we’re unable to get through to Tehran.”

Fed up with the telephone operator’s recurring inability to get a line to Iran, my father hung up and dialed the garage attendant in our midtown Manhattan apartment building.

“This is Karmel Elghanayan from Apt. 31-H,” he said. “Would you please bring my car out?” Soon he was heading down FDR Drive in his brown-and-beige Cadillac toward a shop in Greenwich Village where he’d buy a shortwave radio.

He needed news.

The morning of May 9, I woke to a house full of disheveled and tired people — folks I was used to seeing in our apartment at lunch or dinner. I had no idea something cataclysmic had occurred.

Just a few days earlier, on March 15, 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had locked away my grandfather, a powerful businessman and Jewish community leader, in Tehran’s Qasr prison. Since talking with our few relatives and friends still in Iran had become increasingly difficult, Radio Iran’s shortwave broadcasts became the next best option for the most up-to-date details on the Iranian Revolution’s progress.

My father unpacked the big black box and tested the radio’s reception around our 31st floor apartment. He settled on a corner of the bathroom sink near a narrow window facing east, where the sounds were clearest from 6,000 miles away.

That spring, when I was turning 7, Farsi-language news blared from the radio every day. My father never missed the broadcast in the morning, New York time, for Tehran’s evening news, or the one at night for early morning developments.Some weekend mornings, I’d sit on the floor outside the bathroom and watch him shave while he listened to Radio Iran before heading out for breakfast with my mother, Helen, and my younger brother, Shahram, at the Greek diner across the street on 58th Street and First Avenue.

We had moved to New York almost two years earlier, in the summer of 1977, after my father decided he didn’t want to raise us in Iran. Two years before that, in 1975, it was the shah’s secret service — not Khomeini’s revolutionaries — that had taken my grandfather from his house in the middle of the night and held him for months before releasing him. Now a theocratic ruler had taken over from the monarch and imprisoned my grandfather again. By the first week of May, revolutionary firing squads had executed some 200 people, almost all of them members of the deposed shah’s government, military and secret service.

At 10:30 p.m. on May 8, 1979, my father tuned in as he did every night for the 6 a.m. news from Tehran. He planned on getting up early the next morning for synagogue services to mark my grandmother Nikkou Jan’s yartzeit, the traditional religious ceremony commemorating the one-year anniversary of her death. In his striped cotton pajamas and burgundy leather slippers, he stood facing the mirror in the white marble bathroom to listen.

Eight men were executed today. Among them was millionaire businessman Habib Elghanian.

As the announcer went on with the report, my father stood motionless in stunned silence. My mother, hearing her father-in-law’s name on the radio, ran into the bathroom. My brother and I were asleep in our rooms.

On Long Island, my father’s youngest brother, Sina, had nodded off with his shortwave radio murmuring on. His pregnant wife, Sheryl, heard the news and shook him awake.

As word of my grandfather’s execution spread in the middle of the night, friends and family from Long Island and Queens hurried to our place. Others who lived in our building threw on robes and took the elevator to our apartment. The morning of May 9, I woke to a house full of disheveled and tired people — folks I was used to seeing in our apartment at lunch or dinner. I had no idea something cataclysmic had occurred. My mother fed me breakfast, then took me down to the lobby outside of which a small yellow school bus waited outside to take me to the Lycée Français, where I was finishing first grade.

My father’s sister, my aunt Mahnaz, who was in New York, was spared the late-night phone call. Shortly after her two boys had gone off to grade school, her cousins arrived at her Upper East Side place, their faces telegraphing the sorrow they were about to utter.

The family began mourning my grandfather even as it marked my grandmother’s yartzeit.

By that evening, reports of my grandfather’s execution had spread around the globe. On ABC’s “World News Tonight,” anchor Peter Jennings, with a map of Iran chromakeyed over his left shoulder showing the capital Tehran and a silhouette of a rifle across the yellow outline of the nation, announced the news. “Elsewhere overseas today, there were more executions in Iran,” he intoned. “They’ve become almost commonplace. But today’s give rise to increased concern for Iran’s minority groups. Among the eight men who faced an Islamic firing squad today was a leading Jewish businessman, the first member of that troubled community to be convicted of associating, in the words of the court, ‘with Israel and Zionism.’ Jews in Iran fear that accusation from militant Muslims more than any other.”

On the “CBS Evening News,” Walter Cronkite reported: “An Iranian firing squad in Tehran today executed eight more persons, including a prominent Jewish businessman accused of having links with Israel. In Washington, the State Department renewed its strong disapproval of the summary trials and executions.” As to the businessman’s death, Cronkite said, “it was indicated that he was tried as an individual, not as a Jewish leader.”

A Washington Post editorial the next week noted how outrageous the accusation of “spying for Israel and raising funds for Israel to bomb Palestinians” was. “What this seems to come down to was that he had met some Israeli figures in the early 1960s and had contributed to Israeli causes,” the newspaper wrote. “In other words, he was murdered for being a Jew friendly to Zionism. In no other country in the world is this a capital offense.”

Amnesty International later found numerous violations of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including arbitrary arrest and detention, punishment for a crime that did not constitute a criminal offense at the time it was committed, denial of freedom of religion, and of the right to defense through an attorney and the right to appeal.

What the initial reports did not immediately presage, however, was that the execution would be a watershed for both Iran’s economy and the future of the nation’s Jewish community. That evening’s news also couldn’t foretell how the U.S. Congress’ reaction to my grandfather’s execution would become Khomeini’s excuse for cutting diplomatic relations with the United States — with repercussions still felt today.

What the initial reports did not immediately presage, however, was that the execution would be a watershed for both Iran’s economy and the future of the nation’s Jewish community.

In Tehran that fateful night, Revolutionary Guards pulled into my grandfather’s driveway with large trucks to empty the home of its furnishings. The longtime nanny, Layla Khanoum, and the caretaker,Vali, were still there. They watched the guards stuff the trucks with beds, sofas, chairs, tables, even family albums.

“Please,” Layla Khanoum pleaded with one of them as he plundered the house. “I raised these children. Please let me keep some of their pictures.”

“Stop,” the guardsman admonished her. “These albums are not yours.”

“Please let me keep just a few of the children,” she begged, tears cascading down her wrinkled face.

Back in New York, when my father tried calling his brother, Fred, in Iran, the overseas operator offered the same maddening refrain:

“Sorry sir, we’re unable to get through to Tehran.”

While our black shortwave droned on in the cold marble bathroom, my grandfather’s bullet-riddled body languished in the prison morgue, with a cardboard sign around his neck. It read: “Habib Elghanian, Zionist Spy.”