As the dust-up over the infamous Google memo earlier this year made clear, a new front in the culture wars is forming around disputes between science and identity politics. Pockets of scientists and self-proclaimed “skeptics” are uniting around the notion that politics related to the identities of people of color, women, LGBTQ individuals, people with disabilities, and Muslims represent an adulteration of the fruits of scientific rationalism and “Enlightenment values.”

This romanticized view, however, conveniently ignores less palatable elements of 18th century Enlightenment history — like chattel slavery — in an attempt to frame identity as an irrational or purely ideological distraction from scientific fact. Progressive activists, critics say, are engaging in a self-defeating exercise by emphasizing feelings and political views over pragmatism and common sense. Moderate and left-leaning critics of identity politics argue further that an overemphasis on identity concerns undermines political solidarity.

This sloppy application of scientific knowledge in order to further white supremacy actually has a long history in the U.S.

We see a similar logic playing out in “alt-right” or white supremacist circles, which rally behind white “identitarians” like Richard Spencer but disavow the identity politics of feminists and Black Lives Matter activists. Indeed, just as far-right groups have taken an interest in what are otherwise relatively obscure corners of academia (like evolutionary psychology and medieval studies), they’ve found strange bedfellows in scientists and other prominent rationalists.

The sloppy application of scientific knowledge to further white supremacy has a long history in the U.S.

These individuals reject white supremacy but are also opposed to identity politics and political correctness. Harvard cognitive scientist Steven Pinker, for example, has received plaudits from “alt-right” figures for questioning those who raise issues like gender and racial representation in science.

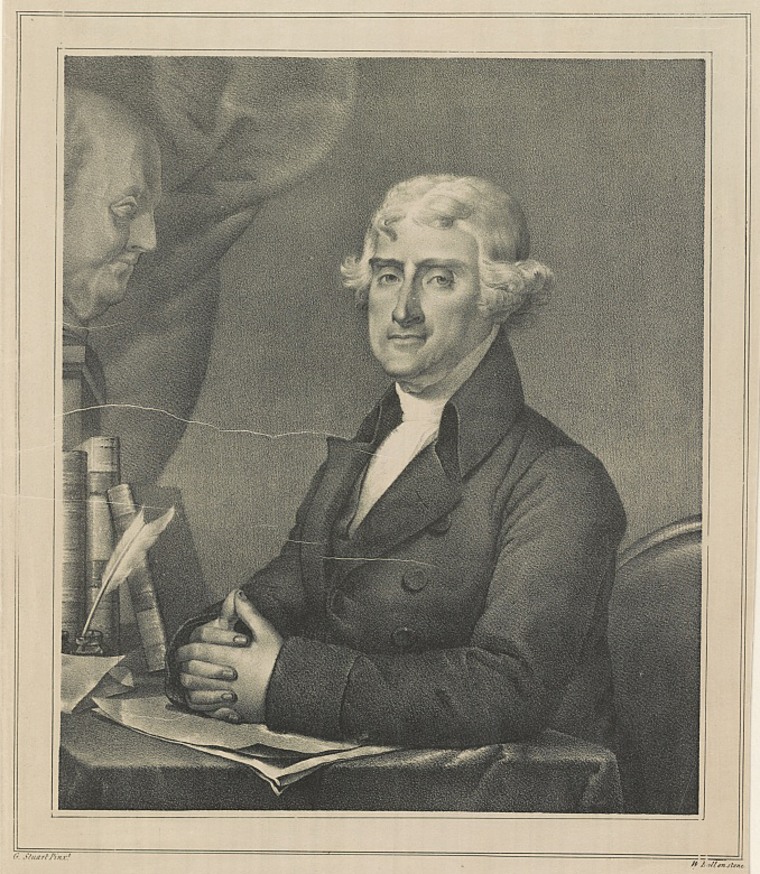

Centuries before the rise of the alt-right, Thomas Jefferson, author of perhaps the most famous words of the American Revolution — “all men are created equal” — also believed that black people were “much inferior” to white people in reason, comprehension and imagination. This may help explain how Jefferson was able to pen the Declaration of Independence and also own hundreds of slaves over his lifetime.

That American luminaries like Jefferson, who believed genuinely in individual freedom, used science to justify a legal framework that granted rights and citizenship according to the race doesn’t mean all Enlightenment ideas are racist. But it does show how identity politics and racism went hand-in-hand during a period we’re fond of referring to as the Age of Reason.

Today progressives and “alt-right” rationalists squabble over whether race is a “social construct” or biological fact — a false and misleading dichotomy that arises more from methodological turf wars than from an understanding of how the concept of race has changed over time. But our contemporary notion of race was actually born in the Enlightenment, at the intersection of science and identity politics. The Enlightenment-lead shift in our understanding of race laid the foundation for how we understand racism today.

Faced with the conundrum of believing in individual liberty while living in societies that reaped the fruits of the Atlantic slave trade, Enlightenment thinkers from Voltaire to Johann Blumenbach created a human taxonomy. This system categorized Caucasians as, in Blumenbach’s words, “the most beautiful race of men,” while the African man was labeled, in Voltaire’s words, an “animal” with “a flat and black nose with little or hardly any intelligence.”

Voltaire’s description is particularly telling, as it aligns observable characteristics (phenotype) with an unrelated and unscientific impression of character and diminished intelligence. This is a textbook example of scientific racism, the misapplication of scientific knowledge to justify a belief in white supremacy.

Whereas throughout much of the 18th century the word “race” was used to describe national and geographical identity, not skin color, Enlightenment thinkers like Blumenbach introduced scientific theories that applied taxonomy to human traits, drawing on the influential work of Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus.

But Blumenbach took Linnaeus’ biological classification system a step further by creating a hierarchy of worth based on physical appearance, forever altering the concept of race.

These theories lent legitimacy to the stereotypes on which slavers relied to hold human beings in bondage and keep the slavery economy running. Phenotype or differences of appearance are not Enlightenment constructs, of course. But it was during the Enlightenment that certain characteristics — like skin color and facial features — became widespread signifiers of character and intelligence.

Scientists and rationalists whitewash the Enlightenment to score points against identity politics.

Today’s scientific racism sometimes involves misappropriating scientific findings (as in the Google memo), or over-interpreting data (as in, I would argue, Charles Murray’s "The Bell Curve" or Jason Richwine’s doctoral work). But it increasingly involves the adoption of a generally scientific or rationalist attitude to dismiss the political concerns of women, LGBTQ individuals and people of color as fanciful or irrational.

In such cases, as with statistician Nassim Taleb’s critique of classicist Mary Beard over the ethnic diversity of Roman Britain, practitioners of scientific racism may portray identity concerns as superficial, and thus as distortions of Real Knowledge. Often, as in Taleb’s case, the move to situate race and identity outside the scope of rational concerns requires either historical ignorance or historical distortion to pull off.

Thus, while Enlightenment values like rationalism and skepticism ostensibly guide the modern case against identity politics, they also explain the relevance and importance of identity politics throughout Western history.

Today we see how that historical affinity is utilized for ever-sinister purposes. Proponents of the “Dark Enlightenment,” for example, have even found a way to justify white supremacy. This intellectual fringe borrows from Enlightenment scientific racism to make the case for eugenics and racial segregation, but rejects Enlightenment egalitarianism and democratic virtues. Thus, while scientists and rationalists whitewash the Enlightenment to score points against identity politics, some white supremacists are keeping the bathwater.

The far-right continues to misuse science in the service of an identity politics of white supremacy. For this reason we can no longer afford to ignore the deep historical connection between science and identity politics. For every rationalist who argues that identity politics is just another form of discrimination, there’s a cadre of white supremacists nodding in approval.

Aaron Hanlon an Assistant Professor of English at Colby College where he specializes in 18th-century British and transatlantic literatures, as well as literature and culture of the Enlightenment. His essays about politics, literature, teaching and higher education have appeared in The New York Times, The New Republic, The Atlantic, Salon, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Ploughshares Blog, The Chronicle of Higher Education and others.