What better way to market wellness to men than to cloak it in the language of violence? That’s been a $1.6 million winning bet for a former Netflix-creative-turned wellness founder who launched a canned water company with the slogan, “Murder Your Thirst.”

That’s right — canned water, because bottled water wasn’t enough.

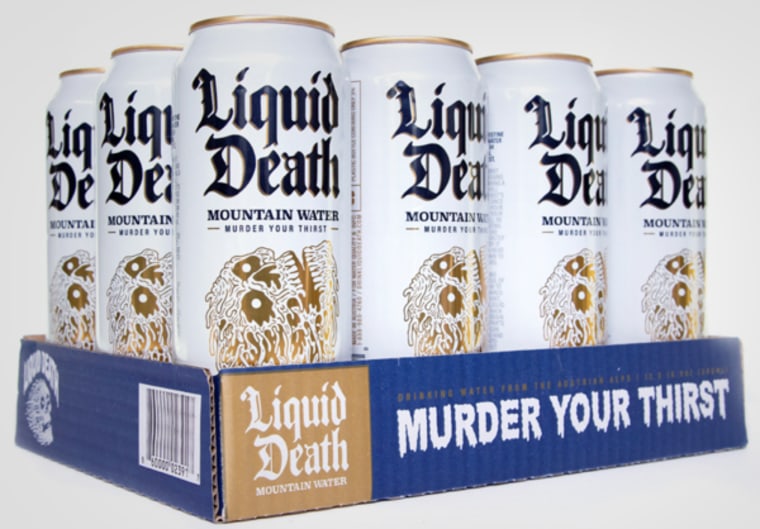

The brand is called Liquid Death; investors like Twitter founder Biz Stone and the woman behind the charge-your-phone luggage company Away think it'll work because the tropical color scheme of a Fiji or the pretty pinks and baby blues of an Evian bottle will never tap into the Everyman's inner desire to hold a molten skull in his hand. (The logo also bears an Old English font, like any of a dozen low-end beer brands.)

By Cessario’s own account, he’s not solely marketing to the whole heavily male punk and death metal crowd indicated by the skull logo; he’s targeting the “straight-edgers" — those who eschew drugs and alcohol in a scene often known for both — and doing so under the guise of eco-friendliness because a single, shiny nickel from every $1.83, 16.9 oz. can sold will support cleaning up plastics from the ocean.

SIGN UP FOR THE THINK WEEKLY NEWSLETTER HERE

Liquid Death’s founder, though, initially gave away the game, when he said who his target wasn't: The “Whole Foods yoga moms,” as he’s quoted. We know exactly what kind of image that phrase projects: A petite white woman in exorbitantly priced spandex, possibly with a Starbucks coffee cup in hand. She’s the corollary to the straight-edge metal man who believes in saving the oceans with a can that sports a molten skull instead of the mountain and river streams that adorn ladies' bottle waters. (Apparently, depictions of actual nature landscapes are somehow not masculine enough.)

In a statement, Cessario denied that the marketing was gendered, claiming that his comments about yoga moms were designed "to make the point that the health food industry has a very narrow minded view of what health-conscious consumers are into."

"This then translates into health food advertising featuring 'aspirational' fitness models and airbrushed celebrities," he said, "nothing weird or irreverent."

Whole Foods shoppers might not be his target (after all, their branded 365 Everyday Value water costs 79 cents a bottle, no mountains or trees in sight, and water cartons ring up about 99 cents), but his stereotypical "yoga mom" is certainly being targeted by someone, too — and that’s the dangerous thing about how “wellness" is sold.

Marketing has the ability to convey powerful messaging, drive consumer behavior and legitimize messages we frequently see and hear about ourselves. It simultaneously guides our aspirations and affirms how we see ourselves. When the marketing used to sell wellness brands to the public validates questionable ideas about gender — and, for that matter, race — we should collectively cringe.

This exact same conversation could — and should — be had about the health and wellness websites of the world that overwhelmingly target young white women, rarely showcasing any diversity in gender, skin color, religion, body size or, frankly, perspective. Such sites are telling people that fitness is the sole dominion of thin white women, which is a conversation frequently had within communities of color.

In a country in which fighting chronic illness is an expensive endeavor, costing us millions of lives (and billions of dollars) because we’re unable to make “healthy” lifestyles accessible, we don't benefit from the gendered marketing of wellness, especially when the gendered images are rarely diverse in presentation.

Often, “wellness" is marketed in a way that only endangers the public instead of empowering it; the advertising makes the snake oil look shiny. For men, health resources come cloaked in magazines covered with shirtless übermensch, promises of “improved performance” — whatever that means — or, sometimes, Charles Barkley. Passive aggressive comments about how “your lady” will enjoy the “new you” also tap into fears of not being able to sexually satisfy one’s partner, a conversation a man should be having with his partner and his doctor, not an advertisement.

Meanwhile, the most current data shows that we lose hundreds of thousands of men of all backgrounds from chronic illnesses like heart disease annually—something potentially worsened by these kinds of over-the-counter "performance enhancers"— and suggests that the numbers will only continue to rise. And, for women, the numbers are high, but there’s a caveat: Because women's doctors rarely listen to their health concerns, and because symptom recognition and pharmaceutical testing were targeted towards the male body, these figures could actually be even higher.

Add in the adverse health outcomes for black and brown communities, sometimes left out of our conversations about health and wellness entirely, and the situation gets even more opaque.

Does this all fall on the shoulders of the 16.9 oz can of water? Of course not. Marketing to sober people trying to fit into a boozy culture while having less of an environmental impact is an interesting idea wrapped in creepy packaging that will draw support (in part because of criticism). I'm actually not opposed to it in its entirety: More people need to be drinking water and, if this is what it takes to get that, so be it. But what it should also do is make us wonder about what is sold to us and how. What message does its success elevate? What does it mean that it takes a brand called “Liquid Death” to compel people to drink water?"

And do we really need another opportunity to put melting skulls on things, as if we didn’t already live through the Ed Hardy era?