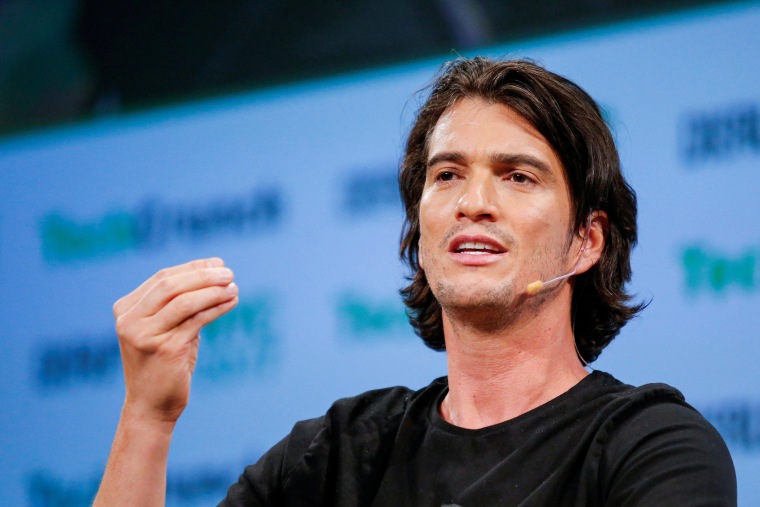

With every passing week, the company formerly known as WeWork lurches from bad to worse. The news that former CEO Adam Neumann will walk away from the mess with over a billion dollars in his pocket, while the shares of workers are basically worthless, is even leading to calls to investigate him for fraud.

But the fallout could be even greater as investors begin to question whether the business model pursued by many of the biggest and most successful tech companies of the past decade is really worth it. CEOs like Neumann generate massive venture capital to capture a monopoly, but so far the profits they promise have been elusive. Uber was the standard-bearer for the model, but its share price has plummeted since going public in May and the struggles of the company could be pulling it down even further, along with all of its imitators.

CEOs like Neumann generate massive venture capital to capture a monopoly, but so far the profits they promise have been elusive.

The WeWork situation is an unmitigated disaster for employees. But it’s also the perfect illustration of how broken the system has become. Founders make off with billions as workers are punished for following their direction.

WeWork’s problems really kicked off in August when it published its IPO filings, leading to immediate concerns over the personality cult surrounding Neumann — referred to simply as “Adam” in the filings — and whether the company could ever turn a profit. As criticism escalated, the IPO was shelved on Sept. 16 and Neumann’s resignation followed on Sept. 24.

Ahead of the IPO, Neumann had already cashed out $700 million, and an exposé by The Wall Street Journal on his partying and management style added to concerns he was just using WeWork to enrich himself. SoftBank, a Japanese conglomerate whose Vision Fund is invested in many of these money-losing “tech” companies, is now taking over WeWork at a valuation of around $8 billion — far below its $47 billion peak. It’s so desperate to get rid of Neumann that it’s buying out the rest of his shares in a deal that will net him another $1.7 billion.

Neumann may be the only one who walks away happy from the WeWork fiasco; the workers certainly won’t. As part of SoftBank’s takeover, it plans to lay off up to 4,000 WeWork employees, and that’s after their stock options have been decimated. At an $8 billion valuation, their holdings are practically worthless and it’s unlikely SoftBank will do much for them.

Part of what makes this tragedy possible is the dual-class share structure of many tech companies, which allows founders to remain in control without owning a majority of the company. Essentially, one of Neumann’s shares was worth a lot more than a share owned by one of his employees. This is why even though 68 percent of ordinary shareholders voted to replace Mark Zuckerberg as chairman of Facebook, he remains in the top position. Neumann was reportedly planning for his grandchildren to control WeWork.

While abolishing this kind of shares structure would give more power to investors, it wouldn’t totally solve the problem. For that, workers need power. Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren proposes allowing workers to elect 40 percent of board members, which has been shown to result in more long-term decision-making and higher levels of pay equality in Germany. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., goes further, proposing workers control 45 percent of board seats and up to 20 percent of their company’s shares, from which they would be paid a dividend. Both plans would give workers a greater ability to protect their interests and ensure the company they work for isn’t simply run to generate a payoff for executives when and if the business starts to implode.

Workers need these kinds of protections as soon as possible. Already, we’re seeing companies feeling similar pressure. Teledentistry startup SmileDirectClub’s share price plummeted after its September IPO, food-delivery app Postmates, delayed its IPO, and the CEO of scooter-rental company Bird says the company is refocusing on improving unit economics instead of pursuing growth as its main competitor, Lime, is on track to post a $300 million operating loss in 2019.

Another factor is a business strategy known as “predatory pricing.” Recode’s Rani Molla explains that many of the companies trying to gain a dominant market position by losing a ton of money position themselves as being in the "tech" space despite offering a traditional product or service. By selling themselves as tech companies, they arguably have easier access to capital, which can help them undercut their traditional competitors. Matt Stoller, a fellow at the anti-monopoly Open Markets Institute, notes that such a strategy used to be illegal, but it’s been enthusiastically taken up by Silicon Valley.

However, the easy access to capital that made all of these money-losing startups possible may finally be coming to end. Uber’s IPO was a real red flag, and WeWork’s collapse set off alarm bells. Uber’s already cut more than 1,000 jobs over the past few months as it tries to rein in its spending after reporting a $5.2 billion loss last quarter, but that might not be enough.

The gig economy delivered benefits for a small percentage of young, relatively well-off people who could take frequent advantage of VC-subsidized services, but the larger social costs have only begun to be quantified: increased congestion, lower transit ridership and more traffic deaths thanks to Uber and Lyft; higher rents in cities with Airbnb; and the erosion of a century of worker protections as the promise of “innovation” kept regulators at bay.

For a decade, tech founders promised they were transforming the economy, but the troubles of WeWork and Uber suggest, rather, that they were burning cash to benefit people like them while making life more difficult for a lot of urban residents. The best way to end this problematic model would be make sure cultish founders like Adam Neumann share power with workers — who have a much greater investment in the company’s long-term success, anyway.