I have lived a fortunate life. I, literally and proverbially, have been to the mountaintop. I have met the most extraordinary people and enjoyed the most amazing experiences. I have ridden horses across prairies and motorcycles across the country. I have watched the miracle of my children growing into adulthood. I have lived the entire spectrum of emotions; I have felt tremendous joy and the deepest pain; I have loved and hated; I have gone to the extremes and savored passions. I have felt ecstasy. I was born in 1931; in my lifetime I have witnessed the discovery of antibiotics and the elimination of dreaded diseases, I have seen the inventions of television and the Internet and the microwave; I have watched with awe the growth of commercial aviation as well as the NFL. Mine has been a life that has spanned eight decades of excitement and discovery and relationships and a lot of luck.

So I sure wasn't ready for it to end.

I have also seen death in its many forms. I have seen death in the natural order of things as my parents aged and died. I have seen the tragedy of accidental death as my wife died in a truly tragic event. I have seen the close and painful death from disease of my close friends. I have held my dying animals in my arms as their life slipped away. I have felt the pain of loss, the emptiness. I have attended more funerals than I can count; I have searched for the right words to console countless bereaved people. I have wandered aimlessly trying to comprehend death, realizing I could never understand it. But in 2016 I had an entirely different encounter with death.

I was told by a doctor I had a terminal disease. That I was going to die.

I have wandered aimlessly trying to comprehend death, realizing I could never understand it. But in 2016 I had an entirely different encounter with death.

Wait a second. This was something completely different. I had gotten very good at being sympathetic; I was the one who always went home at the end of the funeral. I didn't know how to react to this news. This truly was my funeral we were talking about.

"You have cancer," the doctor told me.

There must be some mistake, I thought. This is what happens to other people. This diagnosis was the end result of a chain beginning with my curiosity. While reading a magazine, I had learned that researchers had discovered that cancer cells give off a protein that essentially announces their presence. Scientists had developed a test that can search out this protein. It is an extremely sensitive test. My wife, Elizabeth, and I decided to take this test. When it revealed that she had cervical cancer, we went through a month of near hysteria, but other doctors ran more thorough tests and found nothing. That test was too sensitive, they told us.

And then I was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Me! My regular doctor explained that prostate cancer sometimes is very aggressive and sometimes is so benign you’ll die of something else long before it kills you. Kills me? That couldn’t be happening. To find out which type it was, he took my PSA, a marker for this disease. Until then it had been at one or two, well within safe limits. “It’s ten,” he reported. “That is an aggressive cancer.” Ten! My body had betrayed me.

I have always felt like the great comedian George Burns, who lived to 100: I couldn’t die as long as I was booked. And my schedule was too busy for me to find the time to die. On an intellectual level, I understood my prognosis; I had made out my will, which said that when I died this person got this, that person got that. But on an emotional level, I was certain I was never going to die. I denied it. To me, it was make out my will, then have a nice piece of strudel. Death didn’t apply to me.

I remember noticing in the last few years that when I made personal appearances more and more people were asking more frequently and passionately for my autograph. I knew what that meant: They were expecting me to die soon and my autograph was suddenly going to become more valuable. Boy, I thought, am I going to fool them!

My initial reactions to the diagnosis were, I suppose, quite common: denial, fear, anger — as well as a dose of being insulted.

My initial reactions to the diagnosis were, I suppose, quite common: denial, fear, anger — as well as a dose of being insulted. I am in my eighties; I have lived a long life, but I certainly wasn’t ready for it to end. I decided I wasn’t going gentle into that good night. I was going to fight. I had new horses arriving and I had to ride them. I had personal appearances scheduled and my one-man show to do and I couldn’t let down the audience. I was going to make a movie. And I was supported in a sea of love: my wife, children, my grandchildren. I have always believed there is a force that burns inside all of us, a burning desire to live that permeates all our cells, and I tried to ignite that. I tried to find the trigger to put my immune system in super kill mode. I don’t have any idea if it helped or not, but I believed my immune system got fired up! I was not going to die easily.

Then I read that in certain cases testosterone supplements might have something to do with prostate cancer. I was taking them. I asked my doctor if I should stop taking the supplements. “Yeah,” he agreed, “that would be a good idea.”

I stopped. Three months later I took another PSA test. It had gone down to one. One. The doctor guessed that the testosterone had resulted in the elevated PSA level. I didn’t bother taking the sensitive test. As the cancer specialists explained to Elizabeth and me, we get cancer cells all the time and usually your body eats them up. Your killer cells, T-cells, attack and destroy them. The body gets cancer all the time and eliminates it, but that test is so sensitive it picked up the hint of it and combined with the PSA reading convinced me I was dying.

And while I was sorry to disappoint all of those people with my autograph, I was thrilled to learn I did not have cancer. I’m back to not dying. At least right away.

But during those three months I was living with my death sentence, I spent considerable time thinking about my life, about the lessons I’ve learned, the places I’ve been, the miracles I’ve seen, all of those encounters and events and experiences that have been wrapped together into one great burst of energy called life. And based on that I want to share with you, for the first time, my secret to live a good, long life:

Don't die.

That’s it; that’s the secret. Simply keep living and try not to slow down.

Many people have shared their secrets to a long and happy life. Do this; don’t do that. Eat pickles. Don’t eat pickles. And everyone of them has worked — for them. Other people have passed along the wisdom they have gained. Meditate. Don’t hold in your anger. Treat people as you want to be treated — unless you don’t like somebody; then treat him or her differently. It all works; none of it works. One size doesn’t fit all.

When people come to me and ask for advice, assuming I must have learned something vitally important in my lifetime, I respond with the best possible advice: Don’t follow my advice. Each one of us is unique. Different. Not the same. You didn’t have my mother. No one else can walk in my shoes; most people can’t even fit into them. I can’t wear your shoes; they make my bunions pinch. But why try? We each bring to everyday an entirely different set of experiences and a unique personal point of view. We each see life through a different prism. We are physically, emotionally, and mentally different. We think and see and feel the same things differently. The breeze, the sensation of putting oil on my skin, the anger I feel when some driver cuts me off, my response to a joke or a movie — it’s different, all of it.

For me, really for anyone, to try to tell anyone else how to live their life is the ultimate in hubris. There is no one way, or right way, to do anything. Is there only one path up a mountain? Is there only one way to maintain your health? Is there one way to have a relationship, or is it many and varies depending on whose shoes you have on your feet? I don’t have those answers; maybe the holy men on the top of the mountain do. But they’re living on top of a mountain.

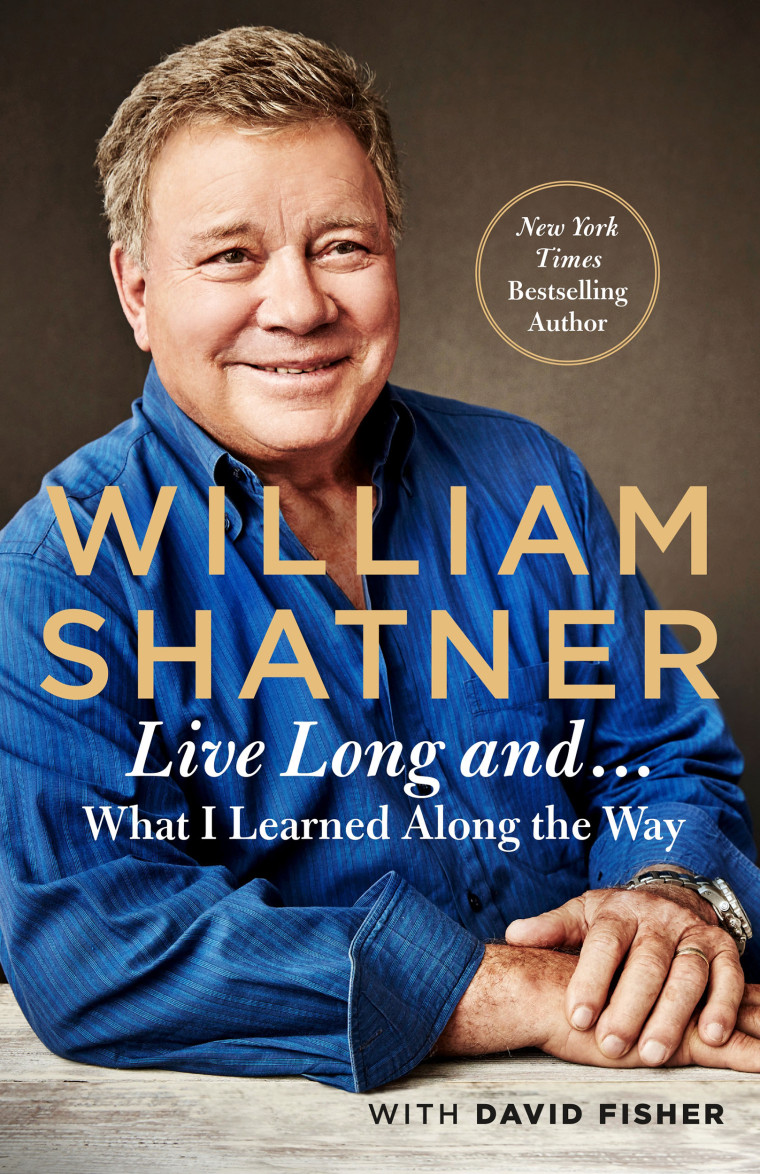

This is an adapted excerpt from "Live Long And..." by William Shatner with David Fisher. Copyright (c) 2018 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin's Press.