“Tess,” my birth mother, had just two pictures of my birth father, whose name I learned was Joe Banks. She gave them to me when, at about 16, I finally worked up the nerve to ask her, not long after I started going to the under-20s dance club called The Speakeasy in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and spending time with Black boys who had Black fathers.

I’d spent a week in Washington, D.C., as part of the Close Up Foundation’s national high school program, and it had emboldened me to lay claim to a biological parent, a lineage and a history that would allow me to keep the joy I felt being with other Black kids as my own. But I needed to see that lineage in my birth father’s face and skin and posture, to take his image and existence out from the filter of Tess’s subterfuge about their history. I felt like photos of him would allow me to piece together my own distillation of who my father was, and who he might be now.

Tess laid the pictures out on her kitchen table, and I touched the worn edges as if they were velvet, and not the creased, yellowing paper of pictures taken from another time. They appeared both vintage and modern, simultaneously relics and urgent pieces of evidence. “They’re yours to keep,” Tess said.

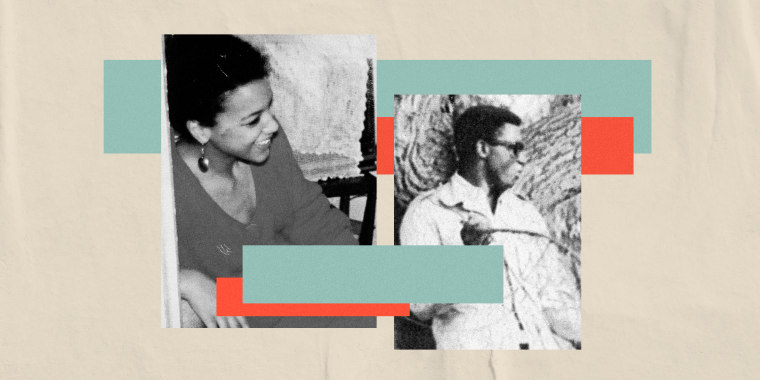

I couldn’t take my eyes off them. One photo, in black and white, featured Tess and Joe in a wooded area, at a bit of a distance. Joe is in profile, leaning up against a tree, tall and narrow-looking with chiseled cheekbones, extending a thin branch of some sort to Tess, whose hand is reaching out to receive it. He’s wearing a light-colored safari-style jacket and fitted pants hemmed at the ankle, loafers, dark sunglasses and a short, tight afro. Tess, in jeans and white sneakers, has on a hooded windbreaker, her shoulder-length hair is pulled back in a low ponytail and her mouth is ajar, as if she’s saying something to Joe.

“I think I may have been pregnant with you in this one,” she said.

“Really?”

“That looks like the fall, and I got pregnant with you in August. I mean, I wouldn’t have known I was pregnant because I was in total denial,” Tess said. That was something she’d said before — but I’d already gone back into the pictures, immersed in the images of my Black father, suddenly feeling deeply attached to him.

The second photo was in color but also of the two of them, more close-up, Tess and Joe sitting on the grass among friends — at a political rally of some sort, Tess told me. Joe, again in profile, is wearing the same cargo jacket from the other picture, the same dark sunglasses, leaning back on his arms, looking forward, nose sloping down toward his lips. Tess is looking straight at the camera, her hair down and tucked behind her ears, wearing regular glasses and a denim jacket.

Even though I was sitting there staring at pictures of my actual birth father, Tess’s comment suddenly reduced him to a faceless, stereotypical Black man in America.

“Joe loved to be seen,” Tess said. “And he was cool as a cuke.”

“He looks it,” I said. “I wish you had a picture of him without the sunglasses.”

“Oh, he wore those sunglasses all the time. It was part of his appeal. He was very stylish, and veeeeeery into his looks.” I had never heard Tess say more than the five words about my birth father — “Basically, he was a dog” — and so this felt exciting, if also slightly unsettling. Why now? I didn’t dare ask.

I wanted to sit with the photos and write a story in my head about me and my Black father. I wondered what he would say to me about these Black boys I found so appealing all of a sudden. Would he call them “jive,” or “young Negro boys,” as Tess had called more than one of them? Would he caution me to stay away from them, or tell me exactly how to handle them — and myself, as his daughter?

“Do you know if I was his only daughter?” I asked.

“I don’t, but you know Black men are often out here having kids with a lot of different women. So who knows?”

As soon as she said that, I lost the thread; the story I was writing shifted. Even though I was sitting there staring at pictures of my actual birth father, Tess’s comment suddenly reduced him to a faceless, stereotypical Black man in America; even my dad, the only father I’d ever known, fell into the void created by Tess’s racism in that moment.

I felt like photos of him would allow me to piece together my own distillation of who my father was, and who he might be now.

I gathered the pictures up and put them in my bag to bring home to my adoptive family in Warner, thinking that when I got home, I would ask Dad his feelings about Black people, whether he’d had any Black friends growing up, and maybe I’d show him the pictures of Joe Banks if he seemed interested.

“The Blacks mostly kept to themselves,” Dad said plainly, when I asked him if he’d ever had any Black friends growing up. “But I was mostly interested in girls — and turtles, of course.”

“But there were Black students at your school in Groton, right?” (Dad had gone to a public high school in Groton, Connecticut, which, he had told me before, was integrated with Black students.)

“Yes, a handful,” he said. “But like I said, they really just preferred to keep to themselves.”

“Did you ever think that might be about self-preservation in a predominantly white environment?”

“I never really thought about it, Beck,” Dad said.

“Did you think about trying to make friends with any of them?”

“They weren’t interested in being friends with white people.”

I needed to see that lineage in my birth father’s face and skin and posture, to take his image and existence out from white people's filters.

"And since then, though?” I said, struggling to map this out in my brain. “No Black friends. You and Mom have never had Black friends.”

“Well, look around, Beck!” Dad laughed, thinking the whiteness of our town and immediate surroundings was funny.

“That’s kind of my point, Dad. Look around!”

“Of course, there was my friend Ling Lee, when I was at the Museum School,” Dad offered. “And he was just a great friend, and all.”

“Also Chinese.”

“Yes, Ling Lee was this little Chinese guy, funny as hell,” Dad said. “I don’t know, Beck. I’ve mostly chosen to live in places where there aren’t that many humans in general. I really need to be around the natural world.”

“But didn’t you think it might be important if you were raising a Black child for her to see other Black people?”

“Mom and I both really thought the world was changing, and that people were coming toward each other,” Dad said. “We really believed what Martin Luther King was saying. And, you know, we had those wonderful years on Pumpkin Hill here in Warner, together and all. And this beautiful house we have now. I mean, how lucky are we?”

In the end, I didn’t show the two pictures I had of my birth father to Dad. Instead, I kept them — and him, and us — to ourselves. Like the Black kids my dad had described in his high school.

Excerpt from "Surviving the White Gaze" by Rebecca Carroll. Copyright © 2021 by Rebecca Carroll. Reprinted with permission from Simon & Schuster, Inc.