I am a 61-year-old retired teacher with $70,000 in student debt. I have been paying these loans my entire adult life. When I admit to other people that I still have student loans, taken out for a bachelor’s I finished in the early ’90s and a master’s I earned a decade ago, they are shocked.

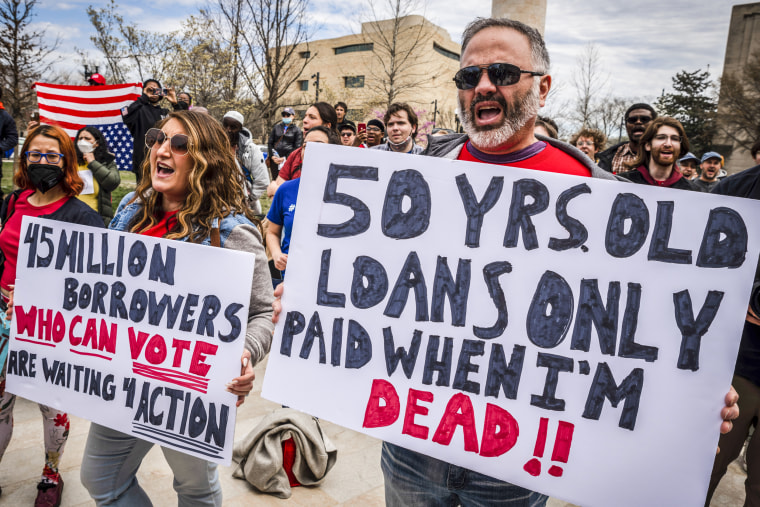

Now I’m here to confess something that many might find even more shocking: I’m never going to pay them back. Instead, I’m joining the fight for student loan cancellation. I am part of the Fifty Over Fifty debt strike, a group of 50 debtors declaring our inability and our unwillingness to pay back our student loans should the White House end the repayment moratorium.

People often think of student debt as a young person’s problem, but it’s not. People my age are the canaries in the coal mine of the student debt crisis.

President Joe Biden announced Wednesday that he’s extending the moratorium, which had been set to expire Aug. 31, until the end of the year, along with forgiveness of up to $10,000 in loans (up to $20,000 for recipients of Pell Grants) for those making under $125,000. But Biden also indicated that the loan moratorium would be the final such reprieve. Instead, he can, and must, cancel all student loan debt once and for all.

People often think of student debt as a young person’s problem, but it’s not. People my age are the canaries in the coal mine of the student debt crisis. The number of older borrowers is increasing at a rate that outpaces all other demographics. Tens of millions of younger folks, who on average had to borrow even larger sums than I did because of the steadily rising cost of college tuition, face even greater hardship.

Meanwhile, colleagues who are 10 or 15 years older than I am experienced a very different reality. At work, I’d often hear from fellow teachers who went to college when the cost was a few hundred dollars per semester. Others used their GI Bill college benefits to pay for tuition. I was glad they were able to earn educations without incurring lifelong debt. But these conversations left me angry that we’ve moved away from a model in which higher education was extremely affordable, and often free, to the exorbitantly priced system we have today.

Once, well-meaning colleagues suggested that I take out a loan on my house to pay off my student debt. This seemed like good advice based on the difference in interest rates. My student loans are fixed at over 7%, and mortgage rates were around 4% at the time. But I knew that if I couldn’t pay my mortgage for any reason, my family would lose our home, which would hardly leave us better off.

I spent 26 years working as a public school teacher, the last 11 of them teaching high-risk youths in an alternative high school. It would seem that one of the existing forgiveness programs offered by the federal government would apply to me. For example, there was a $5,000 forgiveness program for educators like me who were teaching in Title I schools (institutions that help children of low-income families reach academic standards). I filled in the paperwork, had my employer sign the form and mailed it off to the Department of Education. I found out that I couldn’t qualify for $5,000 in forgiveness because my loans were too old.

In 2011, I attempted to enter the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, which promises to erase the remaining balances on Direct Loans after 120 qualifying monthly payments for people working in selected fields. The servicer told me that my husband’s income had to be factored in, as well, to determine what type of relief I’d receive. That resulted in a bill of $1,000 a month for 120 payments, meaning I was paying $50,000 in interest on top of $70,000 in debt — far short of anything resembling forgiveness.

Seven years later, I was going through a divorce and on disability. I called my loan servicer to say I needed to be placed on an “income-driven repayment” plan, a type of program that reduces monthly payments but extends the overall life of a loan. I was making payments of over $500 a month, more than $300 of which was going to interest.

Last year, I tried again when the Education Department announced a Public Service Loan Forgiveness waiver program, an attempt to address the fact that 98% of applicants have been denied in the past. Ten months later, it is still processing my application.

Instead of relief, I get regular notifications from my servicer that it has counted my payments from October 2007, informing me that I have made 143 “eligible” payments while working at a verified public institution and that it disqualified 28 of my payments for some obscure reason, leaving me five payments short of the “qualifying” payments required. The letter told me to keep my job because I need only five more qualifying payments. Various reports confirm that this is all too typical. By some counts, less than 2% of those eligible for relief have been granted it, despite the waiver.

This system is absurd. Over the last 35 years of payments, I have more than covered my principal, but because of the way the Education Department structures its programs and how interest accrues and capitalizes, I am stuck in a debt trap.

I have never been allowed to lower my interest rate, even when the Federal Reserve lowers the prime rate. At times when I was allowed to defer my loan at times I couldn’t pay, the interest still kept accruing. In addition, I have had to consolidate my loans a couple of times to bring down the payment amount. But every time I consolidated, the loan was considered new. That meant that any limit on how long I had to pay it would be reset.

Despite its twists and turns, my story isn’t unique. This is why I have joined the debt strike. I am no longer ashamed of being in debt. I am enraged by the predatory nature of these loans. I am angry that after having made more than enough payments to qualify for forgiveness, I have been told a significant number of my payments don’t qualify for reasons no one can or will explain.

Collectively, the Fifty Over Fifty group owes over $6 million. But all combined, we’ve probably paid that much or more to the federal government over the decades — all for loans that we shouldn’t have had to take out in the first place, because education should be paid for by the government.

Enough is enough. Instead of compounding the harm we’ve experienced, Biden needs to pick up his pen and cancel all student debt — not just $10,000 — for all borrowers automatically, without the ridiculous Rube Goldberg application processes that I have wasted years navigating. We are owed nothing less.