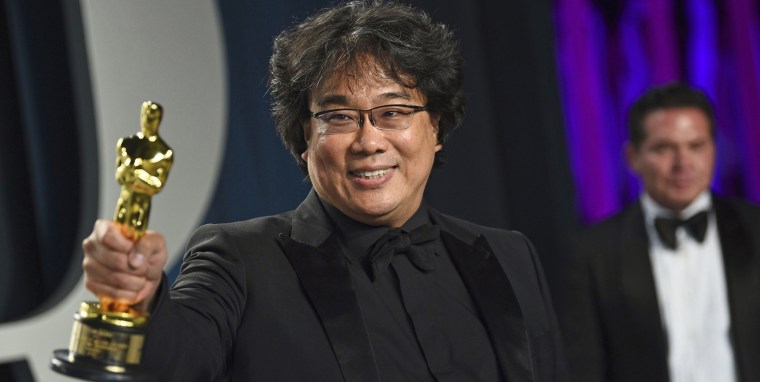

I cannot get the scene of Bong Joon Ho onstage after “Parasite” received the Oscar for best original screenplay out of my mind: Co-writer Han Jin-won is giving his thanks and, just beyond his right shoulder, the audience — and I — can see Bong first marveling and then giggling at the gold statuette in his hands. He is tickled in the moment, as we all were.

To better understand this particular glee for a Korean, it is perhaps just as important to understand its opposite feeling, the feeling of han. It was described by Korean theologist Suh Nam-dong as "a feeling of unresolved resentment against injustices suffered, a sense of helplessness because of the overwhelming odds against one, a feeling of acute pain in one's guts and bowels, making the whole body writhe and squirm, and an obstinate urge to take revenge and to right the wrong — all these combined." It was defined as such during the Japanese occupation of Korea in the early 20th century, and is now said to be woven into the hearts of all Koreans. For Korean Americans, han is less informed by colonization and more by our experiences of racism in our new homeland.

Han also plays a role in “Parasite,” a story heavily balanced on class discrimination and the growing wealth gap. There’s a scene in which Ki-taek, the patriarch of the down-and-out Kim family, along with his daughter and son, are hiding beneath a coffee table — unbeknownst to the prosperous Mr. and Mrs. Park, who are getting intimate on the couch just inches away. It’s a fraught moment, as we fear the Kim family will be caught by the Parks, which then turns sour when Mr. Park tells his wife about the scent that Mr. Kim carries, suggesting the underprivileged have a smell from having to ride subways, etc. In this moment, Ki-taek’s han is palpable: He’s embarrassed at his station in life, shamed in front of his own children and, therefore, angry. Ki-taek’s whole personality changes from here on out: The humorous, dopey dad now stews in han, waiting to avenge his moment of injustice.

In Korea, if you were to win the lottery, you would probably say “kkum-inya saengsinya” which simply put means: Am I dreaming or is this real life? It’s a kind of exuberance that is so opposite the concept of han that it need not be born of revenge or justice served. Rather, it appreciates what is without reference of what wasn’t. This is the rapturous moment in which Koreans found our hero, Bong, when gazing upon the first of four Oscars he would hold that night.

I’d chosen, as I often do, to not watch the Oscars. Despite multiple nominations for “Parasite,” I had no faith the academy would vote in its favor. Then, when the text messages and social media updates began to pour in. I felt a sense of pride in the movie, and in being Korean that I’m not sure I had felt before, and it was wonderful.

I have friends who were brought to tears with the announcement of each of the honors for “Parasite,” that finally ended in sobbing fits which I’m sure rivaled the most dramatic of Korean dramas. They couldn’t say exactly what it was about it that moved them to cry, but that it had so much to do with finally being seen, with the struggles our immigrant parents all suffered, and so much more than many of us have yet to fully articulate.

Alternately, I have friends who, as they watched Koreans fill the stage, discovered they’d dissociated from the Korean part of their identity, stemming from childhoods filled with racial epithets and stereotypes that led to decades to self-erasure and unstated desires to be that model minority, that “good Asian.”

One friend described watching the Oscars: When someone in the room said, “Aren’t you excited? These are your people,” it was only in that moment that she recognized the embarrassment that had been stored in her mind and heart for decades. It unlocked her shame about broken English, about the scent of kimchi on our collective breath or as perceived on our clothes.

There’s a whole barrage of things people of color must suffer through in America. With Asians, other Americans — children, teens, and adults alike — will pull the corners of their eyes up, out or down, mimic buck teeth, and put on “Chinese” accents. You’ll be called a “chink,” no matter from where on the earth’s largest continent your parents or other ancestors hail. You’re expected to be good with numbers. Asian women will be hypersexualized while Asian men will be desexualized. You will be asked how often you eat dog meat.

For many, this fosters a sense of self-loathing and to deal with that, a dissociation from your own cultural identity begins — as well as a deep-seeded resentment. It also meant sometimes laughing along with your perpetrator, making racially-charged jokes at your own expense and rolling your eyes at the movies you did want to see — the things you felt even tangentially connected to like “The Joy Luck Club” or “Better Luck Tomorrow.” The only Korean media you had would be the dozens of VHS tapes your parents rented and would watch every night, at which you’d shrug your shoulders and say, “I dunno, some Korean stuff” if anyone would ask about it.

Korean cinema only first garnered international critical acclaim in the early 2000s, with Park Chan-wook’s “Oldboy” (2003) and Bong’s “The Host” (2006). It wasn’t only movies, though: The interest in Korean media spilled over into Korean dramas and K-Pop and, eventually, Korean barbecue caught the attention of America’s urban foodie palates. Korean culture finally began to gain some traction in the American pop/urban landscape in the last two decades and, while Korean life began to permeate the once seemingly impenetrable membrane of American culture, Asian Americans were simultaneously developing a sense of community with each other through our continent of origin and a shared experience of discrimination.

Still, it wasn't until now that a Korean film was even nominated for any Oscar.

“Parasite” is the first Korean film to be nominated for any Oscar, and was nominated in six different award categories and won in four — including as first foreign language film to win for best picture. In the academy’s 92-year history, foreign-language films have only been nominated 12 times in total. This is truly a defining moment for South Korean cinema, getting the praise for which it’s longed for and deserved.

For South Koreans, the four wins of “Parasite” at the Academy Awards are an incomparable and immeasurable cultural success. For Korean Americans, they are also a point of pride and a moment to examine ourselves with the same joy with which Bong looked at his very first Oscar. For the Korean diaspora, we all feel seen.