Two Supreme Court decisions issued in the early 1970s definitively answer today’s central question of the Russia investigation: Can special counsel Robert Mueller successfully subpoena President Donald Trump to testify before a federal grand jury? The answer, according to existing precedent, is a resounding “Yes.”

The first of these opinions dealt a fatal blow to claims by journalists that they should be exempt from testifying before a grand jury about their sources. In a strongly-worded 5-4 opinion in Branzburg v. Hayes in 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court both extolled the broad scope of a grand jury inquiry and rejected the notion that persons of high rank or importance could avoid becoming grand jury witnesses.

Can special counsel Robert Mueller successfully subpoena President Donald Trump to testify before a federal grand jury? The answer, according to existing precedent, is a resounding “Yes.”

The case centered around subpoenas issued by prosecutors in three states that were consolidated into a single appeal in the Supreme Court. The subpoenas commanded journalists to testify about sources related to civil unrest and illegal drug use. The journalists cited the First Amendment and argued that, at a minimum, the grand jury had to exhaust all sources of information before journalists could be required to testify.

In rejecting the media’s legal argument, the court in colorful language lauded the critical role of the grand jury and the duty of every person to provide evidence if subpoenaed. Describing the grand jury, the court wrote:

Because its task is to inquire into the existence of possible criminal conduct and to return only well founded indictments, its investigative powers are necessarily broad. It is a grand inquest, a body with powers of investigation and inquisition, the scope of whose inquiries is not to be limited narrowly by questions of propriety or forecasts of the probable result of the investigation, or by doubts whether any particular individual will be found properly subject to an accusation of crime.

Issues of propriety, indeed. The main point here is that no one is more important and no one’s work is too critical to be exempt from being hauled before a grand jury. In a footnote (where the court sometimes injects telling legal points) the court cited English philosopher Jeremy Bentham making the proposition that not even the “Prince of Wales” can refuse to testify. As shown two years later, this rule encompasses the president, too.

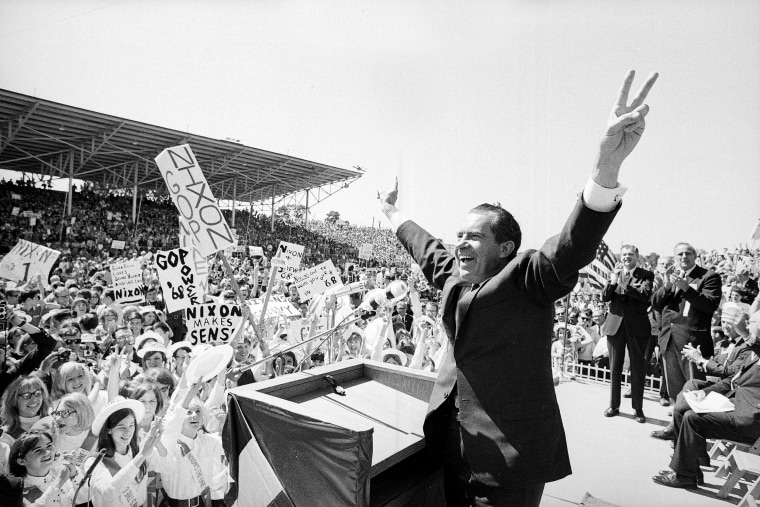

In 1974, when I was counsel to the House Judiciary Committee in the impeachment inquiry of President Richard Nixon, the president flaunted congressional subpoenas for White House tapes, producing only misleading edited transcripts. But the president’s stonewalling of the special prosecutor’s judicial subpoenas cratered in a resounding Supreme Court loss.

In United States v. Nixon, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled the president had to comply with a federal court trial subpoena by producing White House tapes. Importantly, the Nixon ruling relied on, and in fact directly quoted, its then-recent Branzburg opinion for the legal principle that every citizen must obey a federal subpoena:

Only recently the Court restated the ancient proposition of law, albeit in the context of a grand jury inquiry, rather than a trial, that "the public... has a right to every man's evidence," except for those persons protected by a constitutional, common law, or statutory privilege…

Ironically, it is more difficult to enforce a trial subpoena, rather than a grand jury subpoena, because the witness’s testimony has to be demonstrably admissible at the criminal trial before a court will enforce the subpoena. In contrast, the grand jury scope is investigatory and witnesses are routinely called to testify to help the grand jury determine whether or not a crime has occurred. The witness in a grand jury need not have any admissible testimony.

Taken together, the two Supreme Court opinions are a laser-like beacon signaling the outcome of a judicial fight over the enforceability of a subpoena calling on the president to testify before a grand jury.

Thus, the president’s counsel would be wise to reach a compromise about the contours of a supervised interview by Mueller’s team rather than fight a losing battle in the courts. Such a fight would doubtless lead both to an unfavorable judicial opinion and the president appearing — without counsel — before the grand jury.

As they say in television police procedurals, “We can do this the easy way or the hard way.” If the president’s team chooses the “hard way” and fights a subpoena, he may end up all alone in a grand jury room.

Michael M. Conway was counsel to the U.S. House Judiciary Committee in the impeachment inquiry of President Richard M. Nixon in 1974. Conway is a graduate of Yale Law School, a fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers and a retired partner of Foley & Lardner LLP in Chicago.