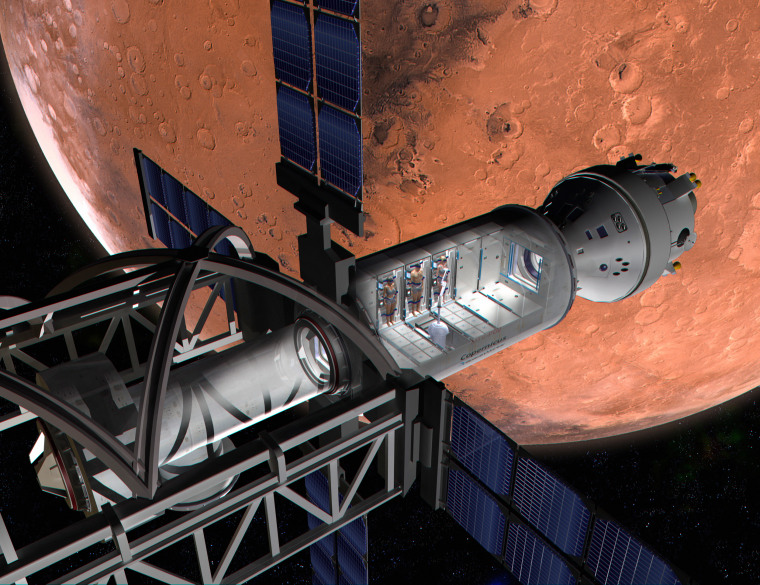

If humans are ever going to get off this rock and seriously start exploring the solar system, we’re going to need better ways to travel. Right now, a journey to Mars takes six months, minimum. To visit Saturn’s intriguing, lake-dotted moon Titan, astronauts would have to be locked in a tin can for an untenable seven years. Something’s got to give.

One of the biggest obstacles to space travel is the biology of the crew, says Dr. John Bradford, president of Atlanta-based SpaceWorks Enterprises, Inc. Astronauts are essentially a burden, burning through supplies, taking up precious space, and risking injury — at least while they’re awake.

So Bradford wants to put them to sleep.

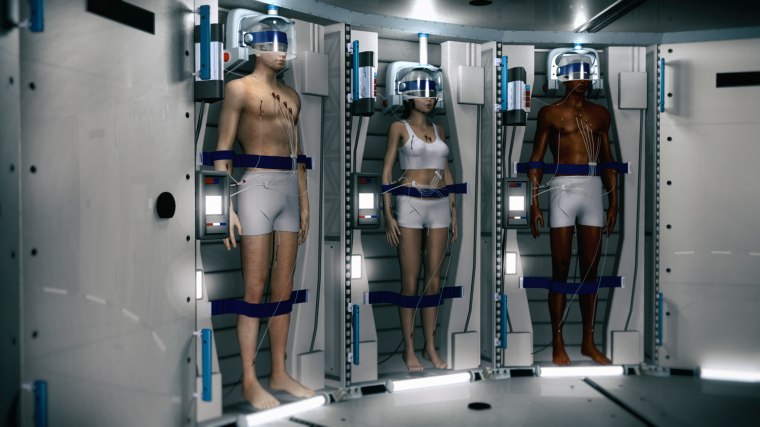

Funded by grants from NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts, SpaceWorks has developed a detailed plan for putting spacefarers into induced torpor. The sleeplike condition, triggered by a dramatic cooling of the body, echoes the suspended animation depicted in science fiction movies ranging from "Planet of the Apes" to "Passengers."

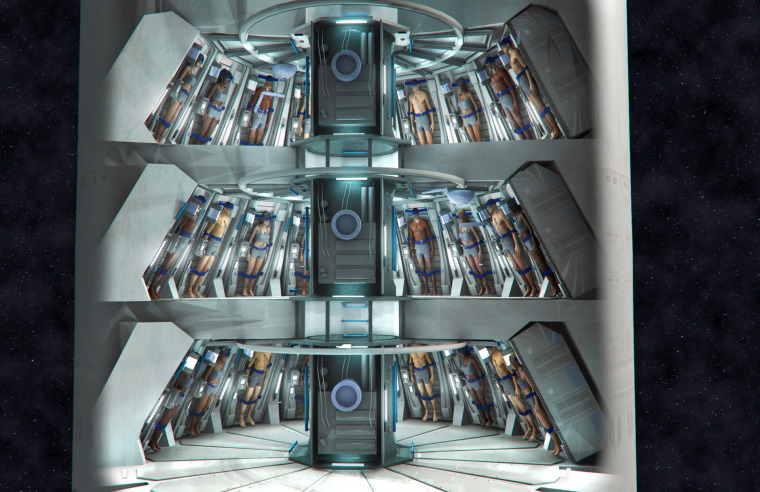

A recently released report shows how SpaceWorks’ proposed “torpor habitat” could cut the size and power of the spacecraft needed for a manned mission to Mars by 55 percent; onboard consumables could be cut by 70 percent. And rather than slowly going stir-crazy in a cramped capsule, the astronauts — and possibly Mars colonists — could dream away the months.

“I haven’t seen any other single technology that can have this much of an impact, short of some exotic propulsion system like an antimatter drive,” Bradford says. “This is in a league of its own.”

Rip van Winkle to Mars

Despite its sci-fi aura, SpaceWorks’ plan has real-world precedent. Hospitals around the world routinely use a technique called therapeutic hypothermia, in which ice packs, nasal coolants, and related tools drastically reduce a patient’s body temperature. The goal is to slow metabolic processes and curb the tissue damage that occurs in the aftermath of cardiac arrest or traumatic brain injury. The patient enters the same kind of torpor that SpaceWorks envisions for astronauts.

But there are some catches.

Dr. Douglas Talk, a California physician and SpaceWorks consultant, notes that therapeutic hypothermia patients shiver as their bodies try to warm up. Keeping astronauts in extended torpor, he says, will require drugs to prevent shivering (which could bring them out of stasis) as well as continuous medical monitoring.

There are also unresolved questions about how long astronauts can remain knocked out without risking physical or mental harm. In hospitals, therapeutic hypothermia is used for no more than 72 hours. Researchers are only beginning to explore what happens after that.

“Small studies show that healthy humans can stay in stasis for up to two weeks with no significant adverse effects,” Talk says. “There’s no reason to believe the limit can’t be extended.”

The SpaceWorks concept takes those studies as its starting point. A four-person Mars crew would enter two-week cycles of torpor, each followed by brief revival and another cycle of torpor. While in semi-stasis, the astronauts would receive intravenous nutrition and sedation.

Bradford and company have also presented a grander vision for a 100-passenger Mars ship that would go far beyond anything NASA has proposed. The ship would consist of two 48-person torpor habitats and four caretakers (the ones who drew the short straw, presumably) watching over them.

Long-duration torpor “shows great promise as a means to enable settlement of the solar system,” the SpaceWorks team concludes.

Mystery of Zzzzzs

Beyond the logistical benefits of using a smaller, simpler spaceship, putting a crew into a sleeplike state could alleviate some of the health concerns associated with space travel. “Potential benefits include reduced bone-density loss and decreased visual impairment,” Talk says. Animal studies suggest that quasi-hibernating travelers will also be less susceptible to the damaging effects of cosmic radiation.

But extended torpor wouldn’t interrupt the aging process, as seen in Hollywood’s takes on suspended animation. In real-world spaceflight, no one is going to sleep for centuries and then wake without having aged a day.

“My guess is that at best we would see one day of increased life span for every three in hibernation, but this is simply based on the fact that we can slow the metabolic processes of the body by 30 to 40 percent with torpor,” Talk says, emphasizing the word guess.

Guesswork and extrapolation are recurring themes in suspended-animation research. Dr. Kelly Drew, a University of Alaska researcher whose work helped inspire the SpaceWorks team, notes that the entire field exists in a scientific gray area. Given the uncertainty, induced torpor might not work as well as hoped — or it might work even better.

One exciting possibility is that humans, like black bears and ground squirrels, may be capable of true hibernation even without sedation and cooling.

“All mammals likely have the genes to hibernate, but expression of these genes is suppressed,” Drew says. She is experimenting with a compound called N6-cyclohexyl adenosine, or CHA, which seems to activate that latent ability to trigger a hibernation-like state in pigs. If it works for them, why not for us?

Researchers at the European Space Agency, meanwhile, are testing to see if they can induce hibernation via electrical stimulation of the hypothalamus, a brain region that links the nervous system to the endocrine system.

This is early-stage research, so it’s hard to draw conclusions. Sleep and hibernation may be more familiar than Bradford’s rhetorical antimatter drive, but in many ways they’re just as mysterious.

The crucial next step will be clinical trials in which torpor is tried on human subjects. “We could start short-duration human testing within one year, and probably know the limits of human hibernation in the next 10,” Talk says. “All it would take is the right motivation and funding.”

And then, long before we are setting foot on other worlds, we could be exploring previously unsuspected capabilities locked away within ourselves.