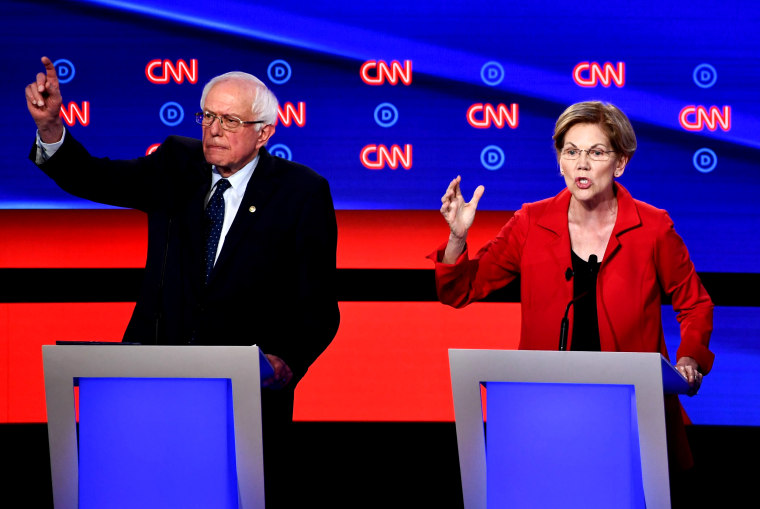

On the first night of the Democratic presidential debate on CNN on Tuesday, the gulf between Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren and everyone else on stage was absolutely clear. Warren opened with a call for “big, structural change,” while Sanders gave a laundry list of the ways corporate America is prospering while average Americans suffer. The popular progressives were in command of the narrative as they called out the Republican framings used by the moderators and their colleagues — something that isn’t new to either of them.

Although Warren has become a standard-bearer for progressives, Sanders’ campaign for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination fundamentally altered American political discourse. Before his insurgent candidacy, ideas like a $15 minimum wage, tuition-free college and "Medicare for All" were viewed as radical demands with little institutional support. But now, less than four years later, these views are increasingly common, including among the crowded field of 2020 Democratic candidates.

Lost in some of the coverage of these policies, however, is the fundamental question of why they are so necessary.

Lost in some of the coverage of these policies, however, is the fundamental question of why they are so necessary. The United States, once the beacon of freedom and opportunity for oppressed peoples around the world, no longer stands up to its reputation. Housing costs have soared, wages have stagnated, and structures designed to lift up those at the bottom have been systematically decimated. America is no longer the land of opportunity where, as the Constitution says, all are created equal.

Conservatives disagree, of course. As Fox News pundit Laura Ingraham tweeted before the first night of the debate on Tuesday, Sanders is “not very interested in freedom.” But what does “freedom” in this sense even mean?

Money has always provided an advantage, but now, more than ever, social mobility is dependent on existing advantage, further privileging the rich and disadvantaging the poor. The United States has fallen near the bottom of social mobility rankings, while the Nordic countries that Sanders cited frequently during his previous run are at the top. It may be blasphemous in some political circles to say, but many of the freedoms cherished in America are better realized in other developed countries, which is why Sanders, the progressive left wing of the Democratic Party and a growing number of Americans are convinced it’s time for change.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for the THINK newsletter to get updates on the week's most important cultural analysis

Anu Partanen, the Finnish-American author of “The Nordic Theory of Everything,” writes that for a country so rhetorically committed to the concept of freedom, people in the United States are actually very dependent. For example, the elderly often depend on the support of their children, young adults often still need to depend on their parents, and many people depend on their employers for health insurance. This is in contrast to Nordic societies, which Partanen explains have governments that work to “free the individual from all forms of dependency within the family and in civil society.”

Partanen writes about a “Nordic theory of love” where “the relationship between parents and grown children ought to become one of equals, so that they can express love, affection and support for one another as self-sufficient adults.” It’s not controversial to say that dependency and money complicate human relationships, which is precisely why the Nordic countries have sought to remove or lessen their influence on family bonds.

Counter to the American narratives about big government and the welfare state, Partanen writes that neither concept exists in her native Finland — their closest word translates to “well-being state.” George Lakey, the American author of “Viking Economics,” concurs: “The Nordics are not actually welfare states. They are ‘universal services states.’”

The distinction between means-tested programs and universal services is an important one. Means testing, which is when programs are available only to people below a certain income threshold, not only requires bureaucracy to constantly judge whether are people are eligible, but it limits the number of people who can benefit, robbing the programs of political support. In contrast, universal programs are for everyone and their universality significantly reduces the administrative burden, while making political support much easier to maintain.

Sanders’ campaign recognizes this, and it’s why many of his proposed programs are universal. For example, his education proposals have been criticized by Democratic opponents like Sen. Amy Klobuchar because some children of rich families would also benefit, but ensuring both rich and poor students are included has the potential to increase broad support and create greater resistance to their sabotage by politicians who are ideologically opposed to government services. As Lakey writes, “programs for the poor are poor programs.”

There’s also an important psychological component at play here. Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir, authors of “Scarcity,” explain that when people experience scarcity in the form of time, friendship, food, but especially money, it places a significant restriction on one’s ability to think long-term and make effective decisions. As a result, having to constantly fill out forms and prove your eligibility for a program or benefit can prove so high a barrier that some who need the help can’t access it, whereas universal programs are often far less burdensome to access.

Having to constantly fill out forms and prove your eligibility for a program or benefit can prove so high a barrier that some who need the help can’t access it.

Mullainathan and Shafir identify means-tested programs as particularly hostile to people experiencing the mental effects of scarcity — the very people they’re often supposed to be helping — and instead praise the relief that can be provided by universal programs. They give subsidized child care as an example: Instead of a parent, often a mother, having to arrange for a family member to watch her child or find a day care she can afford, the program provides both cost savings and it lifts some of the mental burden of worrying whether her child is in good hands. This, by the way, is a benefit that will never be captured by a technocratic cost-benefit analysis.

Over the past several decades, as union membership has declined, social programs have been decimated, and the rich got richer, Lakey writes that the United States operated an economic model that valued insecurity: “A family depends on a job that might disappear tomorrow; it lands in a feeble safety net; it has few prospects for finding another job as good or better.” There’s little stability under such a system, and the Great Recession served as a wake-up call for how bad things had become.

How can one actually live a truly fulfilling life when worry and anxiety are around every corner? Sure, the government may be a little more present in Nordic societies, but as Partanen indicates, the programs implemented by those governments make people’s lives easier. People feel a collective ownership of their public services because everyone contributes, everyone benefits and no one has to worry about whether getting sick or losing their jobs will ruin their lives.

If that’s not a prerequisite to freedom, I don’t know what is, and it’s exactly why Sanders wrote in 2013 that the Nordic countries have “a very different understanding of what ‘freedom’ means … Instead of promoting a system which allows a few to have enormous wealth, they have developed a system which guarantees a strong minimal standard of living to all — including the children, the elderly and the disabled.”

After decades of consistently pushing the same message, Sanders has seen his ideas finally enter the political mainstream. Polls have shown him to be the most popular politician in the country, while he and Warren consistently poll second and third place among the Democratic nominees. Both politicians are inspiring a radical, energetic and unapologetic new class of politicians that are shaking things up in Washington and state capitals.

At the end of the debate, both Warren and Sanders harkened back to their working-class roots, called for structural change to take on the rich and powerful and emphasized the necessity of a mass movement to make it happen. People are fed up with the unfairness and lack of freedom that corporate greed has created, and they’re ready for change. Maybe this time they’ll finally get it.