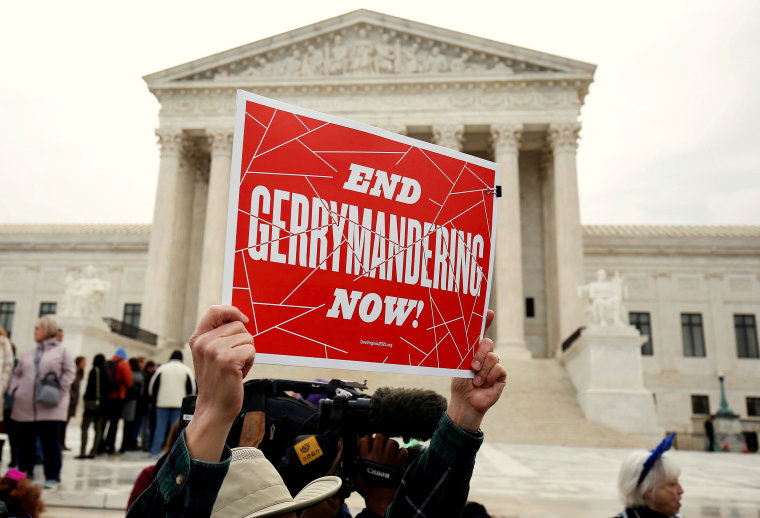

Some of the most consequential cases this U.S. Supreme Court term deal with a decidedly unsexy topic: drawing legislative district lines. This week, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in two cases addressing the topic of partisan gerrymandering, which is the process of drawing district lines to maximize political power.

If the topic of partisan gerrymandering sounds dry, consider this: In some races, the outcome is essentially predetermined as a result of partisan gerrymandering. That is because how state officials draw legislative lines determines the voters and donors who live in each district. Gerrymandering is sometimes referred to as the process of elected officials choosing their voters, instead of voters choosing their elected officials.

If the topic of partisan gerrymandering sounds dry, consider this: In some races, the outcome is essentially predetermined as a result of partisan gerrymandering.

Say in hypothetical "State X," 55 percent of registered voters are Republicans and 45 percent of registered voters are Democrats and there is a 100-member state delegation. One might expect that Republicans would win approximately 55 of those seats with Democrats carrying the remaining 45 seats. But after a little electoral manipulation, Republicans win 70 of the 100 congressional seats, leaving Democrats with the remaining 30 seats. This disparity between the percentage of registered Republicans and the percentage of Republicans elected to statewide office is how partisan gerrymandering works.

SIGN UP FOR THE THINK WEEKLY NEWSLETTER HERE

But how exactly did Republicans accomplish such a victory? Partisan gerrymandering is typically accomplished by either “packing” voters in the minority political party into a few districts, or “cracking” those voters into multiple districts. If voters are packed into a few districts, it means they can only make their voices heard, and elect the candidate of their choosing in a few districts. If voters are cracked into many districts, it means they likely will not be able to garner enough collective votes in any of those districts to elect the candidate of their choosing. In both cases, the political party in power dilutes the voting power of the minority political party.

If partisan gerrymandering sounds unfair, that’s because it is. If it sounds unconstitutional, that’s because it should be. But the Supreme Court has never actually ruled that such actions violate the Constitution.

And this brings us to the two cases that the Supreme Court will be hearing next week. I wrote about one of these cases, Lamone v. Benisek, last Supreme Court term, when the Supreme Court was expected to rule on whether Democrats in Maryland had engaged in partisan gerrymander. But instead, the Supreme Court punted and sent the case back to the lower courts, partly on the theory those challenging the district lines should have brought their claims earlier.

Since the Supreme Court’s decision last June, a lower court in Maryland concluded that the state’s new district lines were indeed unconstitutional and that it had to redraw new district maps for the 2020 elections. Maryland appealed that decision and now the case is back in front of the nation’s highest court.

The second case, Rucho v. Common Cause, deals with North Carolina’s 2016 congressional map. In this case, the Supreme Court is asked to address three questions. First, it must determine whether those challenging the district map have the legal right, called standing, to sue. The doctrine of standing essentially requires that the person suing suffered a real harm and that harm will be remedied if they win the case. Second, the court must decide whether federal courts can get involved with claims of partisan gerrymandering. And third, the court must decide whether the district lines amount to an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. It is worth noting that North Carolina looks a lot like hypothetical "State X" we discussed above. Republicans won 77 percent of congressional districts, but only 53 percent of the statewide vote in 2016.

These cases illustrate yet another instance in which the replacement of Justice Anthony Kennedy with the more conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh will likely make all the difference. In 2004, the Supreme Court also took up the question of gerrymandering. In that year, the justices were divided on whether federal courts have any place hearing these kinds of political disputes and whether the court could come up with a workable standard to evaluate them on. While liberals believed courts can and should get involved, conservatives felt these are decisions are best left up to the legislative branches. Justice Kennedy stood in the middle, for years hemming and hawing about the possibility of finding a standard to review claims of partisan gerrymandering.

But now, with the addition of Justice Kavanaugh, the Supreme Court has shifted to the right. It seems plausible, and in fact quite likely, that the Supreme Court will conclude that federal courts have no place policing claims of partisan gerrymandering. This would essentially legalize vote dilution on a broad scale. It would also ignore the fact that this is exactly the type of situation that calls for judicial intervention. Courts have a role to play in protecting the right to a meaningful vote.

A ruling is expected by the end of June.