The indictment of 13 Russian individuals and organizations by special counsel Robert Mueller provides some useful insight into future elections in America. But when it comes to preventing foreign influence in elections and politics, we have brought a knife to a gunfight.

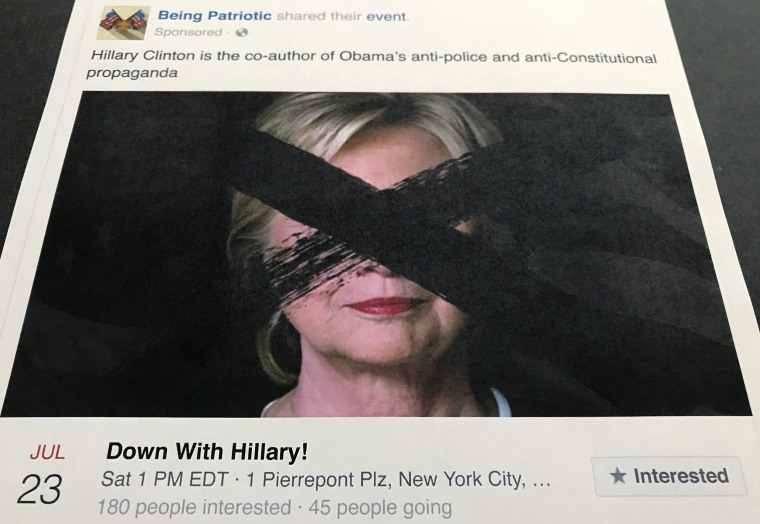

Much of the conduct described in the indictment is labelled “information warfare.” The Russian individuals and organizations are alleged to have, among other things, created fake identifies and social media accounts to attempt to influence the 2016 presidential election.

The Founding Fathers were actually quite worried about interference by foreign nations in our then-fledgling country’s elections. More than 200 years later, those fears continue to be well-founded. Foreign influence in our elections cuts at the heart of democratic self-government. And while the indictments demonstrate that there are laws in place to prevent this behavior, it also shows the deep inadequacy of those laws and the need to rethink our current framework.

Elections laws, are simply not well suited to the type of behavior that is alleged here — a combination of identity theft and undisclosed money pumped into our online world to sway our ballot box decisions. One area that both Congress and the Federal Election Commission have tried and thus far failed to regulate is the spending so-called dark money, meaning undisclosed money, on online advertisements in our recent elections.

The Founding Fathers were actually quite worried about interference by foreign nations in our then-fledgling country’s elections.

Tellingly, our existing election laws may not actually regulate much of the behavior described in the indictment. For obvious reasons, there is a specific prohibition against foreign nationals spending money to “influence[] any election for Federal office.” But most election laws only regulate express advocacy — meaning election ads which clearly and unambiguously advocate for the election or defeat of a candidate. Express advocacy, therefore, actually includes a rather narrow band of communications.

For example, an advertisement which tells you that one candidate beats his wife arguably does not fall within this definition, as it does not expressly tell the viewer not to vote for that candidate. As University of California, Irvine law professor Richard L. Hasen pointed out in August, there may be constitutional problems associated with applying the ban on money spent by foreign nationals to influence our elections to advertisements that do not expressly advocate for the election or defeat of one of the presidential candidates

In addition the problems of interpretation, it is important to remember that most of our election laws were written during a time when we simply could not fathom the reach of the internet. Our lawmakers didn’t envision the rise of online news, online “fake news” and social media, or the decline in institutional journalism — along with the accompanying effects on elections. In some ways this matches a pattern we see in many areas of the law. As technology emerges, behavior changes and lawmakers and judges struggle to stretch and re-define the laws to react to those new behaviors.

If there is one thing that we likely would all agree on after the 2016 elections, it is that we are not all reading from the same script. Before the advent of the internet, the vast majority of us obtained and relied upon the institutional press to provide us with our news coverage. In an article covering the passage of a new piece of legislation, we might, for instance, have disagreed about whether the legislation embodied sound public policy, but we likely would not have disagreed about the veracity of the reporting on that legislation. There have always been conservative, moderate and liberal media outlets. There is always been some level of bias. But there have not always been websites and social media accounts masquerading as media outlets which do little other than peddle false information.

It is difficult to argue with a voter who reads lies and believes them. It is difficult to put our faith in our representative government when many of those picking our representatives are making their decisions based on false information — false information sometimes disseminated straight from the U.S. president via social media. So technology has changed. And our behavior has changed. But the law has not changed enough.

Technology has changed. And our behavior has changed. But the law has not changed enough.

For one thing, it might be time for us to re-think our protection of false political speech. Currently, political lies are essentially protected under the First Amendment. That may have made sense in a pre-internet era in which the marketplace of ideas was better defined, but is it a concept worth revisiting in our fake, fake news moment.

There is also currently a bill pending in the Senate called the Honest Ads Act which should be seriously considered. The bill would, among other things, require certain companies, like Facebook and Twitter, to disclose the identity of those purchasing political ads on their platforms. (Although ideally, we should not have to rely on the government to make these changes. Social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter could make an enormous, positive impact in this area on their own without waiting for new legislation.)

The internet has and will continue to re-shape the way we obtain all of our news and information, including our electoral information, in profound and unexpected ways. We know this. Foreign nationals know this. But we have not done enough to adapt.

And, if we do not take immediate steps to strengthen laws and increase transparency, we can expect more of the same behavior outlined in Mueller’s indictments to occur during the 2018 midterm elections. Nothing less than the integrity of our elections and system of government hangs in the balance.

Jessica A. Levinson is a professor at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, and is the president of the Los Angeles Ethics Commission.