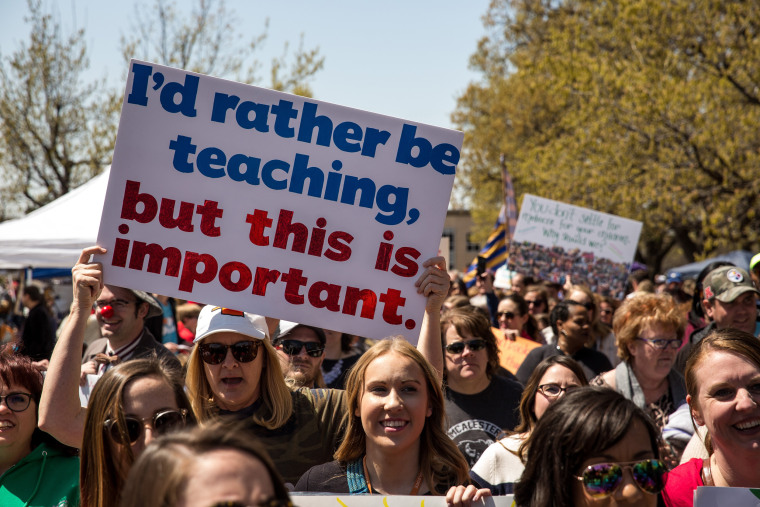

As the recent teacher strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Arizona and elsewhere show, there’s an appetite for a renewed, vigorous 21st century labor movement, in places that Democrats in recent years have written off as unwinnable, deep-red strongholds. That provides an opportunity that Democrats need to seize to convert new voters to the cause and, more importantly, to improve the material lives of workers who have seen their economic power decline and diminish.

By kneecapping unions, Republicans have rigged the political playing field in their favor, which has benefited corporate bosses and hurt workers right where it matters: In their paychecks. For too long, Democrats have allowed that state of affairs to persist.

So if Democrats want to do more than just rack up seats in elections they’re supposed to win in 2018, they need to rediscover their love of labor unions — and this is a perfect moment for just such a step, thanks to teachers all over the country proving that workers can still take the fight to those in power.

Between 1980 and today, Democrats too often took labor for granted, content in the knowledge that unions were not going to start backing the pro-corporate agenda of the Republican Party in any appreciable numbers. They spent their time raising money from finance and tech and other corporate darlings, while extolling the virtues of new companies whose business models are terrible for workers and embracing a liberalism that didn’t put the rank and file front and center. They even backed measures like President Bill Clinton’s ill-fated “welfare reform” that explicitly made life harder for those at the bottom end of the labor scale.

During the Obama years, activists and lefty policy types wanted Congress to pass legislation that would have made it easier for employees to unionize, but it didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, Republicans were actively looking to undermine labor wherever they could, via the proliferation of so-called “right to work” laws — which allow people in union workplaces with collectively bargained benefits to reject union membership (and avoid dues), though they then don’t reap the benefits of union representation in individual disputes with management. Such laws are now on the books in 28 states, and make it harder for unions to raise funds from their members and effectively collectively bargain. (The issue is the subject of recent Supreme Court case that seems likely to end the ability of public sector unions to automatically collect dues.)

Thanks to their sustained work and to the Democrats’ neglect, Republican legislators were successful in substantially driving down the number of workers who are in unions. In the late 1970s, about one-quarter of the American workforce was unionized; last year, it was down to 10.7 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, of which the vast bulk is in the public sector. Private sector union membership is a scant 6.5 percent.

This decline has had two big effects — one economic and one political — about which Democrats should to care. First, lower rates of unionization have translated into lower wages for workers, both union and non-union alike. According to the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank, the wages of non-union men would be five percent higher if union levels had stayed consistent since 1979. Fully one-third of the growth in wage inequality among men and one-fifth of that among women since the 1970s can be explained by declining unionization rates. (The gender difference is due to the fact that women have never reached the same levels of unionization as men.) There’s plenty of other research that comes to similar conclusions.

These numbers make intuitive sense. Lower rates of unionization mean workers are unable to bargain as effectively with their employers for wage hikes; it’s every worker for herself, rather than everyone negotiating as a collective unit that can wield real power and make threats that employers have to take seriously. And since Democrats portray themselves as the party of the people, stagnating wages reflect very badly on them.

Unions are one of the few entities that can somewhat compete with corporations when it comes to campaign financing.

But this isn’t only about dollars and cents; it’s also about political power. Unions are one of the few entities that can somewhat compete with corporations when it comes to campaign financing. Individual workers simply have no chance. Thus the decline in unions has led to a real decline in political heft for the left.

It’s possible to put numbers on just what this has cost Democrats. According to a working paper posted in January by three researchers, the adoption of right to work laws has lost Democrats about 3.5 percentage points in presidential elections, and similar amounts in races for the Senate, House and governors’ mansions. In states that prohibit the establishment of union shops, Democrats win fewer seats in state legislatures, per the numbers, and turnout overall falls (which generally benefits the GOP). Donald Trump did better with union members than any Republican presidential candidate since Ronald Reagan, but that’s simply the final effect of a long string of events sucking votes and money away from Democrats.

That electoral success, of course, leads to more anti-union legislation, as the GOP understands when it has a good thing going. So when Democrats win the day again, the cycle needs to be broken — if they actually want to stay in power for longer than it takes the political pendulum to make its usual swing.

A good place to start would be the recent legislation introduced by Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and co-sponsored by 12 Senate Democrats (including several who are reportedly eying a presidential run in 2020). The legislation would negate state right to work laws, make it easier to form unions, and stop companies from misclassifying workers as independent contractors, among other provisions. It would definitely whack away at the edge employers have when it comes to dictating terms to their employees.

Of course, the bill has no chance of going anywhere so long as Republicans are in power; eliminating right to work in one swoop is a Holy Grail for Democrats and would inevitably face legal challenges and a full court press from business leaders. But it’s exactly that sort of ruthlessness that the GOP has employed to great effect, so Democrats need to respond in kind, through both legislation and the courts.

Reversing some of the damage done by the GOP in recent years, and tilting the political playing field back away from corporate America is of the utmost importance, and not just because of politics. It would make life materially better for workers all across the country. And it might even make America actually great again.

Pat Garofalo is a writer and editor based in Washington, D.C. He was formerly an editor at U.S. News & World Report and ThinkProgress.