President Trump’s threat during his 2019 State of the Union that investigations conducted by Special Counsel Robert Mueller and the newly Democratic House will jeopardize “peace and legislation” will not insulate him from criminal probes and congressional inquiries.

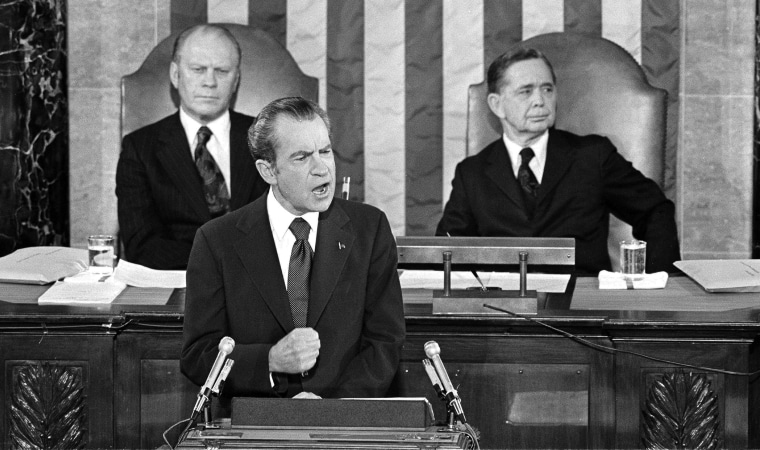

After all, Richard Nixon made similar pronouncements just 45 years ago, when he denounced the then-ongoing Watergate investigation in his own State of the Union address. And Nixon’s attack on prosecutors and the House Judiciary Committee failed to save his presidency.

The similarities are stark. After citing recent job growth statistics as an “economic miracle,” Trump warned on Tuesday night that “ridiculous partisan investigations” would derail America’s economic progress.

On January 30, 1974, Nixon for his part touted the creation of 2.5 million jobs during the five years of his presidency as the biggest increase in 20 years; Trump similarly cited the 304,000 jobs created in January 2019, a statistic issued last Friday.

Trump then bluntly tied the country’s continued prosperity and the passage of any new laws to ending the multiple investigations against the Trump campaign and his administration. “If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation,” he said as written in the prepared text of his constitutionally-required review of the country’s progress. “It just doesn’t work that way.”

Nixon, of course, was no less hostile to the criminal and congressional investigations he was facing, but he held his attack on them until after he had finished delivering his 22,000-word prepared speech and closed the folder containing that text. Nixon then said he wanted to add a “personal word” about the “so-called Watergate affair” investigations.

Nixon then claimed that he had voluntarily given the special prosecutor all “the material he needs” to conclude the investigation. “The time has come to bring that investigation and the other investigations of this matter to an end. One year of Watergate is enough.” The Republican members of Congress applauded rousingly.

Nixon, though, was lying: Not only had he tried to put an end to the investigation months before his address by firing Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, but the Nixon White House had subsequently stonewalled requests to produce White House tapes.

Trump has, of course, attempted to claim the same. Almost a year ago, then-White House lawyer John Dowd asserted that Trump’s cooperation with Special Counsel Robert Mueller had been “unprecedented,” citing the production of 200,000 pages of documents.

Since then, however, Trump has balked at being interviewed by the special counsel, instead providing written answers to some questions, and has repeatedly berated the Mueller investigation as a “witch hunt.”

Prosecutors have, despite Trump’s characterizations of their work, indicted Trump loyalist Roger Stone and Trump’s personal attorney Michael Cohen for lying to Congress, among other charges. Cohen has pled guilty to that charge.

Nixon, in the epilogue to his state of the union in 1974, nonetheless also pledged to cooperate with the House Judiciary Committee, as opposed to the criminal investigation, in its work “in any way that I consider consistent with my responsibilities as president of the United States.” But Nixon qualified his pledge by declaring that he “would not do anything to weaken the office of the president of the United States.”

Nixon’s caveat apparently foretold the White House’s almost-total defiance of subsequent subpoenas from the Judiciary Committee for White House documents and tape recordings relating to 147 specific conversations. The White House response was limited to a collection of so-called “edited transcripts” of 33 tape recorded conversations.

In its final report, the Judiciary Committee characterized the edited transcripts as “untrustworthy.” Comparing the edited transcripts to the recordings of eight tapes supplied by the Watergate grand jury, the report concluded that the transcripts were “inaccurate and incomplete in numerous respects.”

Nixon’s defiance was the basis of Article III of the impeachment resolutions, adopted by the Committee — for willfully disobeying the congressional subpoenas.

Unlike Nixon, Trump has made little pretense of cooperating with congressional investigations. Instead, Trump’s White House counsel’s office hired additional lawyers after the midterm elections to defend against the predicted Democratic-led House investigations and subpoenas.

Both Trump and Nixon used their time before the joint chambers to declare that legislative cooperation with Congress could not occur unless the investigations into their offices ended.

After calling for an end to the Watergate investigation, Nixon said the “time has come” for the president and Congress to address the “great issues” of the day involving “the welfare of all the American people in so many ways as well as the peace of the world.”

Trump struck the same refrain, after deriding “ridiculous partisan investigations,” by stating “We must be united at home to defeat our adversaries abroad.”

Warning that peace is jeopardized without a cessation of the criminal and Congressional investigations of the White House and presidential campaigns proved to be false in 1974.

That threat is likely just as false today.

Nixon’s vow near the end the State of the Union in particular is both eerie in retrospect, and was subsequently broken. After remarking that both the assembled members of Congress and he had been elected by the American people to their respective offices, Nixon said, “I have no intention whatever of ever walking away from the job that the people elected me to do for the people of the United States.”

Just 191 days later — on August 9 — Nixon did just that by resigning as president.