Bob Cousy is a national treasure. The Boston Celtics star point guard of the 1950s and ’60s revolutionized basketball with his creative passing and uncanny court awareness. He helped form the NBA Players Association union so his fellow players could make a better living. He spoke out against racism and befriended African American teammates who played in a city that was often hostile to them. He looked out for the little guy — literally; the 6 foot 1 inch 13-time All-Star for years sponsored a basketball tournament in which all the participants had to be 6 foot 2 or under.

Perfection is not one of the criteria, but heart, intelligence, compassion and influence are.

He will be recognized for this stellar record as a player and human being when he accepts the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Thursday. But he will do so wishing he had done even more.

In November of 2018, I was assigned to produce a radio story for WBUR and NPR's “Only A Game,” a weekly sport storytelling program, about the relationship between Cousy and African American teammate Bill Russell, an 11-time NBA champion, Hall of Famer and outspoken civil rights advocate.

I visited Cousy in his 6,000-square-foot Worcester, Massachusetts, home, where he lives alone. On a cold November morning, the friendly and approachable nonagenarian greeted me at his front door with a handshake.

We sat down at a huge dining room table. Cousy poured out his heart. Most of the tears he shed were for his beloved wife, Missie, who died in 2013. But some of them were for Russell.

"I should have done more" was the steady refrain. Although he had spoken out against racial quotas in the NBA while he was still a player, he hadn't publicly shown support for Russell, who had been the subject of racism in its vilest forms.

Just a few months earlier, the estimable Gary Pomerantz had finished a wonderful book — “The Last Pass: Cousy, Russell, the Celtics, and What Matters in the End” — that first revealed Cousy’s remorse at not doing better by Russell.

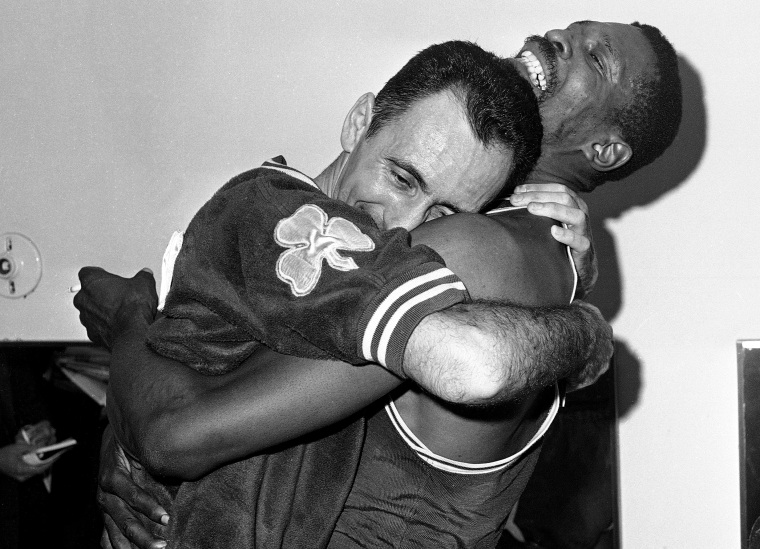

Basically, the story goes like this: Cousy comes along in 1950 and revolutionizes the NBA with his passing and ball-handling skills and his cerebral approach to basketball, but can’t quite get the Celtics over the championship hump. Then, Russell comes along in 1956, revolutionizes the NBA with his defense, rebounding and cerebral approach to the game, and leads the Celtics to its first NBA title in his rookie season. And then leads them to 10 more. On the court, they were very tight. Off the court, not so much.

Cousy had been close friends with other African American Celtics (especially the first black NBA draft pick, Chuck Cooper), but he never enjoyed the same close relationship with Russell. Maybe Cousy was too into being “The Man” and too afraid he was about to be displaced. And maybe Russell was too angry to be approached, incensed as he was about the treatment he and other African Americans were subjected to all over the country. Russell, who received his own Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010, wasn't shy about sharing his anger and contempt.

Cousy would take the occasional overnight train or bus in solidarity with black teammates Cooper, Russell, K.C Jones, Sam Jones and Satch Sanders when they couldn’t find a hotel that would let them stay, but he was relatively silent about what his teammates — especially Russell — had to endure.

When I interviewed Cousy, I reminded him that he was, indeed, supportive of his black teammates at a time when many white players had ignored them (or worse). And that Russell had written about that in his first book, "Go Up for Glory."

Cousy was having none of it. And his internal struggle had to do with more than what he could have done, but didn’t, for Russell.

When the interview was over, I turned off my digital recorder. As I packed up my gear, Cousy shifted to the subject of the Catholic Church's sex abuse scandal. He's always been a practicing Catholic, he told me, but the scandal made it hard for him to maintain any faith in human beings. He was dead serious, just as he had been when talking about Russell.

My story aired in December of 2018, and I was happy with it. But I was troubled that Cousy couldn't — or didn't want to — find closure of any kind on these moral issues. I, perhaps selfishly, wanted a man of his accomplishment and character to find peace late in life. So I tried to do something about that.

I’m Jewish, and I knew that Cousy's senior thesis at Holy Cross was on anti-Semitism. I bought a copy of John Connelly's "From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution on Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933-1965," and I mailed it to him along with a letter gently suggesting that forgiveness was always possible.

A couple weeks later, I got a handwritten letter from Cousy. He informed me, in no uncertain terms, that trying to influence his thinking on this matter was naive at best. He closed his letter with the following: "See, this is the type of cynicism that awaits you when you're 90. Thanks for caring, however. Best, Bob C."

Eight months later, the man who upbraided the somewhat younger idealist is about to receive a lifetime achievement award.

“I don’t deserve the damn thing,”Cousy recently said about receiving the Medal of Freedom. But he does. Perfection is not one of the criteria, but heart, intelligence, compassion and influence are.

Wear it proudly, Bob.