“Patriotism: devotion to and vigorous support for one's country.” — Oxford Dictionary

What it means to be patriotic in America isn’t simple to define anymore. Growing up, I always just thought patriotism meant dressing in red, white and blue, shooting off fireworks and eating hot dogs. I never gave much thought to the meaning of the word beyond the sights and sounds of the Fourth of July. To me, patriotism only took place on specific days and at specific times. Kind of like being religious, my family would say grace at dinner and I’d say my prayers before bed but I didn’t necessarily practice religion as I went about my day. That’s how I viewed patriotism; in school we pledged allegiance to the flag every morning, and at ballgames I took my San Francisco Giants hat off and put my hand on my heart for the anthem, but mostly I just anticipated the chant of “play ball!”

Not until I joined the military and fought on foreign soil did I even begin to appreciate what those songs and symbols stood for, or at least what they stood for to me. Just as it deepened my understanding of patriotism, my experience as a member of the armed forces informed how I view acts of protest — especially in the context of sporting events, which have long been sources of unity and comfort during times of unrest and war.

Just as it deepened my understanding of patriotism, my experience as a member of the armed forces informed how I view acts of protest — especially in the context of sporting events.

"The Star-Spangled Banner” has been performed at professional sporting events for over 100 years. Although there are references to the song as far back as 1862, the first game of the 1918 World Series was likely the event that truly popularized the tradition. That series pitted the Boston Red Sox against the Chicago Cubs with World War I as baseball’s backdrop. Thousands of American troops had already lost their lives overseas, stadium attendance was down and morale was generally low across the country. But during the seventh-inning stretch of the first game at Wrigley Field, something magical happened. As the story goes, the military band (which was a common occurrence at big sporting events back then) began to play "The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The Red Sox third baseman at the time was a sailor named Fred Thomas who was granted furlough by the Navy to play in the series. Thomas snapped to the position of attention, faced the American flag and threw up a salute. Out of respect for him, the other players in the field (including Babe Ruth, who was on the pitcher’s mound) took their hats off as fans in the stands began singing along. It was a powerful moment that was replicated again the following night in Chicago. When the series went back to Fenway Park in Boston for the third game, the Red Sox decided to play the song before play began and even honored some wounded veterans on the field.

Fast forward 13 years to 1931, when President Herbert Hoover signs a law officially making Francis Scott Key's song our national anthem. This move was motivated in part by the anthem’s popularity during sporting events, where it seemed to bring people together. But was it the song that brought people together, or the sporting events themselves? Certainly, the grandstands probably looked very different in 1918 than they do today. For one, the fans dressed in suits and ties were much less diverse — and so were the players in uniform.

Sporting events in America today are unbelievably powerful. We barely talk to our next-door neighbor who we’ve “known” for years, but we go to a ballgame and cheer alongside, high five, and even hug the people around us when our team makes a big play. We don’t give a damn about their politics or religion in those moments; we allow ourselves to just exist as humans, connected by a common passion.

Lately, it seems harder and harder to find these moments of human connection. Two years ago, Colin Kaepernick sat on the bench during the national anthem for the first time before the San Francisco 49ers played the Green Bay Packers in a preseason game. This was the statement he gave after the game explaining why he was protesting: "I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder."

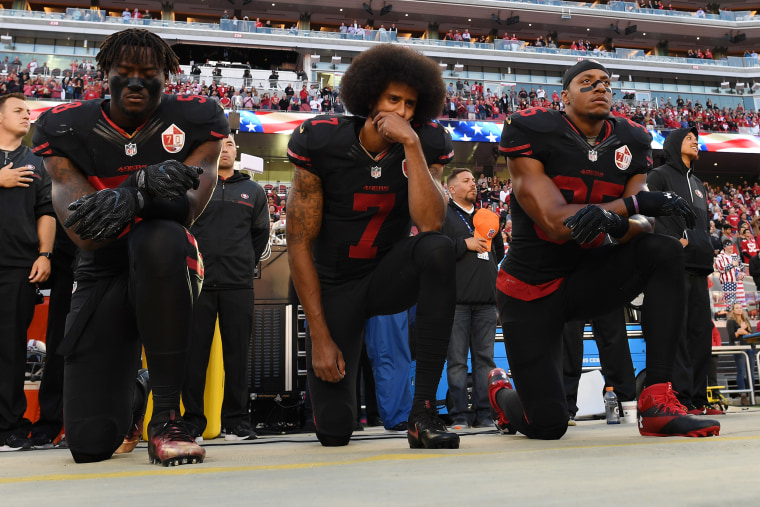

When Kaepernick and I met and talked just six days later, a few hours before the 49ers were set to play the San Diego Chargers, we discussed a lot, but more importantly we listened to each other. I wanted him to stand and he had pledged to sit during the anthem, but we found middle ground: Colin would take a knee, making his statement about police brutality while also respecting the men and women who fought and died for what our flag is supposed to represent.

The men who have followed in Kaepernick’s footsteps say they are not protesting the anthem itself, they are demonstrating during the anthem. It’s an important distinction.

The men who have followed in Kaepernick’s footsteps say they are not protesting the anthem itself, they are demonstrating during the anthem. It’s an important distinction to understand. Personally, I do not endorse Kaepernick’s method of protest but I absolutely support his right to do so. That is an unpopular place to stand these days, in the radical middle, defending someone you somewhat disagree with.

It’s hard for me to grasp why this is so difficult for people (from both ends of the political spectrum) to understand. It’s OK to be different, it’s what makes us the same — embrace it and remember that nobody’s a perfect patriot, especially not me.

In the U.S. Army Special Forces we have a saying: De Oppresso Liber, to free the oppressed. To me, the American flag is not the symbol of a perfect past; it is but the symbol of a hopeful future.