With Major League Baseball sidelined as a consequence of COVID-19, 30 massive stadiums sit idle, silently waiting for cheering fans to fill them once again. As we behold the void in these palaces of sport, it's worth taking a moment to ponder: How did these hulking things get built in the first place?

In his wonderful new book, "Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between," author Eric Nusbaum answers that question for Dodger Stadium. His loving, rigorous rendition of this story — of an ostensibly noble idea undercut by a wave of paranoia and bad faith to allow the depressing triumph of the wealthy and the well-connected — helps us remember that, for all that we rely on sports to entertain us by being modern-day fairy tales, their underpinnings can tear people (and homes) down, not just build them up.

As we behold the void in these palaces of sport, it’s worth taking a moment to ponder: How did these hulking things get built in the first place?

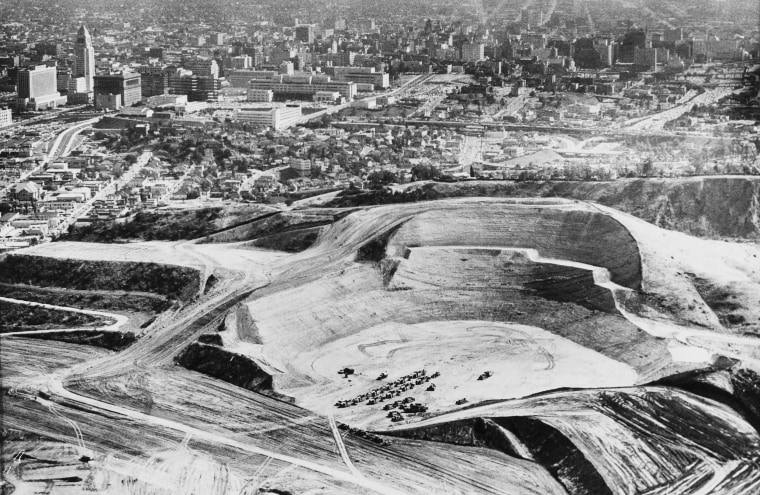

Nusbaum charts the destruction of the communities of Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop, which were tucked in a canyon known as Chavez Ravine smack dab in the middle of Los Angeles. This neglected, makeshift community, primarily the province of poor Mexican families, was to have made way for the construction of Elysian Park Heights, a public housing project spearheaded by city housing official Frank Wilkinson in the 1950s that would provide new homes to those in the community after temporary relocation for construction.

But an aggressive campaign driven by Richard Nixon years before he became president and other red-baiting anti-public housing forces smeared Wilkinson for his membership in the Communist Party USA and effectively dismantled his project, even though the local population had already been displaced.

What ends up happening next transforms Chavez Ravine into a Los Angeles institution for the next 70 years. Walter O'Malley, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, unable to finagle the construction of a new stadium for the team on Long Island, broke the hearts of the Brooklyn faithful (including a young Bernie Sanders) to move the team to Los Angeles and become the first major league team on the West Coast. O'Malley, aided by a ballot initiative approving the sale of the Chavez Ravine land to the Dodgers, proceeded to build a sleek, modernist baseball stadium and a giant parking lot for the recreational pleasure of privileged fans on the land where Mexican American immigrant communities once stood.

What really makes Nusbaum's book sing is the contradictions the author brings to the narrative. He is a lifelong Dodger fan, while Dodger Stadium, a beautiful building where some of the most transcendent moments in sports have taken place, is rooted in malfeasance.

"Chavez Ravine is beautiful and idyllic," he writes in the book's introduction. "It isn't even a place. It's more than that. It's a state of mind, a heightened sense of being that you achieve when you visit. There are palm trees. There are magnificent sunsets and vistas."

Even after Nusbaum spent years digging into the amoral destruction of immigrant communities in service to its construction, Dodger Stadium remains a beacon of light in his life. This is the effect sports have on us — they enchant us, make us fall in love, give us some of the most memorable moments of our lives. Nusbaum's emotion as he chronicles the unseemly way that a place that means so much to him actually came into being highlights the contradictions of being a conscientious sports fan over the last half-century or so.

Then as now, team owners, real estate developers and local politicians leveraged the love cities have for their teams into obscene public paydays for new stadium construction. Mercedes-Benz Stadium, where the Atlanta Falcons play, was subsidized to the tune of $700 million in taxpayer money. Clark County, Nevada, coughed up $750 million to help fund the Las Vegas Raiders' new stadium and coax the team away from Oakland, California. After the New York Mets declared Shea Stadium useless to them in 1998, $616 million in public subsidies went to build their new home, Citi Field. The new Yankee Stadium, built at around the same time? $450 million of taxpayer money.

Even metropolitan stadiums that aren't built with public money involve massive public investment — cops, roads, transit — and shut off large swaths of cities to new housing stock, contributing to the ongoing urban housing crunch.

Perhaps the worst offender is the International Olympic Committee, which sells the games to the public as a celebration of brotherhood and athletic triumph, the temporary transformation of a whole city into a Dodger Stadium populated by people from all over the world. But on the ground, building a bid committee and planning the games aren't a coming together of the world so much as a real estate gold rush. Los Angeles real estate moguls were among those funding LA's recent bid committees.

Publicly funded stadiums and Olympics misadventures aren't wise investments, of course. But it doesn't matter. These stadiums are the homes of memories that sit with people for the rest of their lives; they employ people; they give people common ground to connect on. But the schemers who plan and build our cities are all too willing to weaponize those feelings to recast urban spaces as playgrounds for the rich.

If we're going to keep having stadiums — and, to be clear, I believe we should, that sports and other mass events have a lot of value for communities and individuals (so long as there isn't a pandemic going on, of course) — the construction and development of the spaces where we make them happen need to be subservient to the actual needs of the communities where they are built.